Spring 2009

Bye-Bye Books?

– The Wilson Quarterly

The 500-year-old technology of the book may be poised for assisted living, or maybe even perpetual care.

The 500-year-old technology of the book may be poised for assisted living, or maybe even perpetual care, writes Christine Rosen, senior editor of The New Atlantis. New communications technologies have irrevocably altered the act of reading itself, with “information foraging” replacing solitary deep reading. As computer users scan the screen for content, their eyes zooming across and down the page in search of a missing fact or useful nugget, an entirely different mental process is occurring than in traditional contemplative reading. Reading as we knew it for five centuries may be approaching the status of an “increasingly arcane hobby.”

Television and computers are creating a two-class society: people of the screen and people of the book, according to Rosen. Research suggests that screen people are generating excessive amounts of dopamine, one of the natural neurotransmitters produced by the brain. In some studies, too much of this important but incompletely understood neurochemical has been shown to block activity in the pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain that controls judgment and measures risk. Screen people, in other words, may literally be thinking differently from book people.

There’s another important difference between screen people and book people. In reading a traditional book, the reader has to enter the world the author has created, to succumb to the story, perhaps become “attuned to the complexities of family life, the vicissitudes of social institutions, and the lasting truths of human nature.” But with a screen, Rosen writes, readers become users, the masters. They aren’t required to step outside themselves.

Television and computers are creating a two-class society: people of the screen and people of the book.

Online books, or devices that facilitate their use such as the Kindle, the most popular portable electronic reader, don’t provide the same sensation as reading from a paper volume, Rosen says. Kindle browsing is a lot slower for her, and she finds the device’s many instant search features distracting. It’s particularly unsuited to reading to children. Anybody who tried to read Goodnight Moon to a three-year-old on a Kindle would almost certainly find the toddler more interested in the buttons and the scroll wheel than the story of the great green room itself.

Some of the most avid promoters of handheld devices over printed books dream of linking, manipulating, annotating, tagging, highlighting, bookmarking, and translating boring old works to create a new universal library. A generation raised to crave the stimulation of the screen might simply stop reading the paper book in favor of “fractured, unfixed information.” Rosen fears that literacy, the most empowering achievement of our civilization, will be replaced with a “vague and ill-defined screen savvy.”

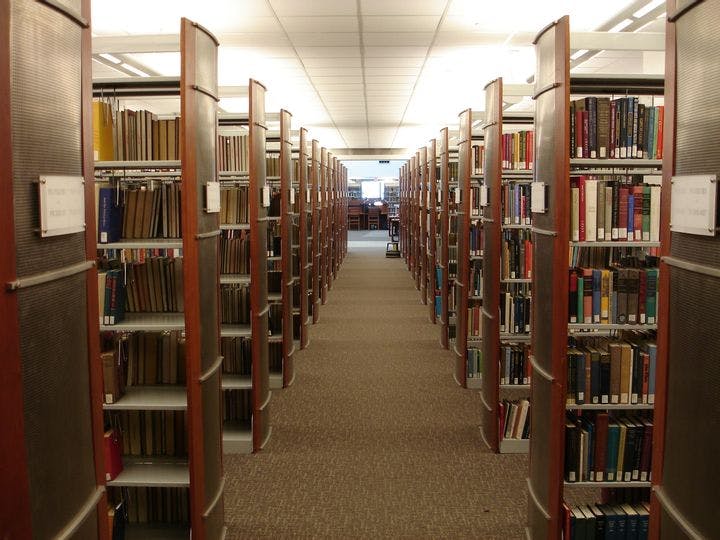

For Anthony Grafton, a professor of history at Princeton, a shift from book learning to screen skimming raises hard questions about the future of the ultimate citadel of the book, the research library. Ironically, research libraries designed to prepare new generations of scholars to maneuver in both the virtual and printed words face a financial crisis caused by the vast increase in the availability and cost of books, journals, and databases, and a space crisis caused by the flood of print materials. Princeton’s Firestone Library adds enough new printed matter every year to fill more than a mile of shelves.

Research libraries, central to college campuses, seem to have diverged toward one of two stereotypes: “reactionary temples of leather and vellum” or ultramodern pseudomalls stocked with banks of humming computers. Most libraries have elements of both, but even untrue stereotypes matter, Grafton says, because they frame much of the current thinking and writing about the future of libraries.

It’s time for collaboration among administrators, scholars, and librarians to bring the “collective intelligence of the swarm to bear on the hive it used to inhabit, and still needs,” according to Grafton. Intelligent and collaborative design of new and renovated research libraries could incorporate both the old and the new. Well-designed ateliers of scholarship might just pull humanists, scientists, teachers, and students back into an environment where serious reading can occur.

THE SOURCES: “People of the Screen” by Christine Rosen, in The New Atlantis, Fall 2008, and “Apocalypse in the Stacks? The Research Library in the Age of Google” by Anthony Grafton, in Daedalus, Winter 2009.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Michael Sauers