Spring 2009

Made in America

– Sarah L. Courteau

Sarah L. Courteau on great Americans.

The self-made man or woman comes off as something of a charlatan anymore. Nearly every day, genetic researchers seem to discover another human trait on which personal gumption doesn’t have all the traction. Genes aside, there’s the latest salvo in the nature vs. nurture debate. In Outliers (2008), America’s sweetheart sociologist, Malcolm Gladwell, argues that the success of those we dub “geniuses,” from Bill Gates to Michael Jordan to, well, Malcolm Gladwell, is little more than the snowballing of luck, privilege, cultural legacies, and other advantages—and that the disadvantages of circumstance and bad luck are overwhelmingly likely to consign us to mediocrity.

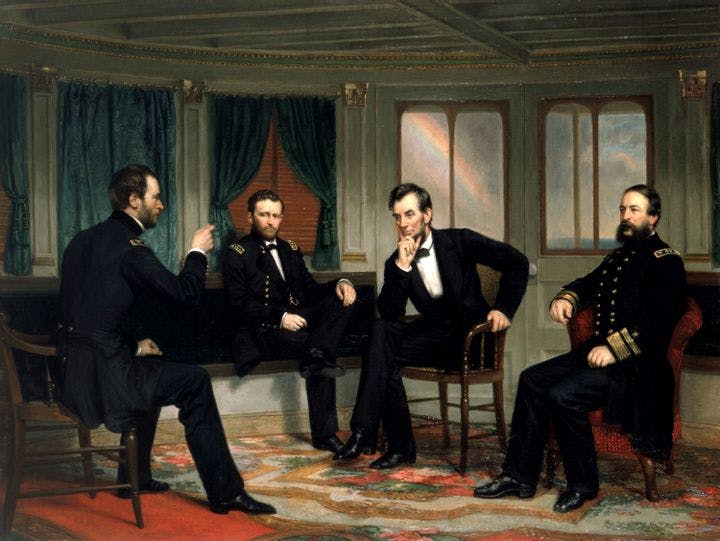

The American creed has never been this deterministic: Smarts and courage are the raw materials of success, yes, but it’s what we choose to do with them that counts. With enough perseverance and hard work, anybody can be somebody. To read How Lincoln Learned to Read with the new calculus in mind makes for a fascinating though ultimately frustrating journey. In this difficult-to-classify volume, Daniel Wolff traces the educations of a dozen influential Americans, ranging from conventional choices, such as Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy, to the likes of Paiute schoolteacher Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins and swivel-hipped crooner Elvis Presley. Wolff himself—poet, music journalist, documentary filmmaker, and author of a book about the New Jersey town where Bruce Springsteen made his name—is difficult to categorize, which is probably why he could get his arms around this disparate cast of characters.

The question that guides Wolff is simple: “How do we learn what we need to know?” His poet’s sensibility homes in on the telling detail or the haunting image. The resulting essays resemble daguerreotypes that time and wear have rendered mostly indistinct, leaving only a few bold lines. Perhaps unwittingly, they show how hard his question is to answer. While Wolff excavates the origins of his subjects deftly enough, he shies away from speculating much about exactly how their “educations,” in and more often out of the classroom, bore on the people they became. Still, his essays remind us that greatness in America can bubble up just about anywhere, and that even the great have trouble understanding the ingredients of their own success.

Whatever the facts of their lives, public figures in America have tended to play up their humble beginnings. In his Autobiography, Benjamin Franklin encouraged the idea that he arrived in colonial Philadelphia in 1723 a runaway just shy of 18, hungry, broke, with no advantages to speak of. In reality, he grew up in the home of a respectable Boston candle and soap maker, was sent to school at age eight for a spell, and cut his rhetorical teeth as an apprentice to his older brother, a printer. When Abraham Lincoln ran for president, 70 years after Franklin’s death, he traded on the same homespun lore, declaring it “a great piece of folly to attempt to make anything out of me or my early life.” His education—a patchwork of winters spent in makeshift schools—he dismissed as “defective,” but it was more than many other frontier children received. Both his intellectually inclined mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, and his book-toting stepmother, Sally Bush Lincoln, strongly influenced him, and during his teenage years tending a store in Rockport, Indiana, he acquainted himself with the raw new nation by reading several newspapers. Yet we’ve tended to perpetuate the “log cabin myth” (as though Lincoln sprang into office directly from a pile of wood shavings), for, Wolff writes, it “confirmed not only Lincoln’s genius but the country’s.”

By the time Elvis Presley, Wolff’s final subject, was of school age, in the 1940s and ’50s, the son of what many dismissed as poor “trash” could spend eight months out of the year in a classroom. Presley’s more important education was his exposure to gospel singing at the Assembly of God churches his family attended in Tupelo, Mississippi, and later in Memphis. Yet Wolff notes that one of the few times Presley grew visibly angry in public was when an interviewer suggested that his style drew from his “holy roller” background. “That’s not it at all! . . . My religion has nothin’ to do with what I do now, because the type of stuff I do now is not religious music.”

Yes, our origins are a touchy business. “An American education,” Wolff observes, “is going to bear the marks of rebellion.” And it stands to reason that go-against-the-grain individuals will reject the notion that their early lives had a whole heap to do with how they got where they are. As Gladwell notes in Outliers, the Horatio Alger mythos is so strong that we reflexively resist the idea that anything but “pluck and initiative” influenced our success. Jeb Bush—son of one American president and brother to another—once described his family roots as a “disadvantage” in his business career, and when he ran for governor in Florida he repeatedly referred to himself as a “self-made man.”

Whatever stories Wolff’s great Americans told themselves and the country, none of them—even the former slave Sojourner Truth—built their success in a vacuum. Much had to go right for that greatness to build, like a pearl around a grain of sand. But still, there’s that small hard nodule of . . . intelligence? ambition? grit? Henry Ford wrestled to account for his success, and finally concluded—conveniently for his mass-production empire—that though hard work is important, some men are born great, while “the average worker, I’m sorry to say . . . wants a job in which he does not have to think.”

Gladwell’s model of success, that opportunities great and small nudge us toward the heights, doesn’t entirely account for the fact that adversity seems to spur some to achievement and simply to crush others. Nor does it explain the trait that marks every individual in Wolff’s book: the ability to see beyond their present circumstances, to imagine another life for themselves. Henry Ford couldn’t reconcile himself to the life of a farmer that was his lot in rural Michigan. He wanted to take machines apart and figure out how they worked. Environmental writer Rachel Carson grew up in Springdale, a Pennsylvania industrial town where women were “expected to settle down with a man and raise a family.” Her older sister took a stenography job after the 10th grade and entered an early, disastrous marriage. Rachel commuted to a neighboring town to finish her high school education, then attended college, rejecting “the idea that she would function as a second-class citizen in a man’s world.”

Wolff’s biographies highlight how little we know, aside from the facts of these lives, about what drove these men and women. Their own accounts reveal more about how they wished to be perceived than about what went on in their minds during those years in schoolhouses, childhood bedrooms, or farm fields. When asked about the education that had made him, Lincoln answered in part: “I can remember going to my little bedroom, after hearing the neighbor’s talk, of an evening, with my father, and spending no small part of the night walking up and down, and trying to make out what was the exact meaning of some of their, to me, dark sayings. I could not sleep, though I often tried to, when I got on such a little hunt after an idea, until I had caught it.” Another boy would have lain down and shut his eyes. If Lincoln paced his room because he was born that way, few of us are ready to discount entirely the idea that some spark in him ignited the curiosity encoded in his DNA.

What drives any of us to greatness? Awash as we are in genetic research, sociological studies, and standardized-test results, we’re not much closer to answering that question. And perhaps that’s for the best. When self-knowledge tempts us to sit back and let DNA and destiny do the heavy lifting, we’re treading where Adam and Eve got into trouble—and in danger of pinning our failures on any number of snakes. What Wolff’s innocent little biographies do illustrate is that, gifted and driven as our leaders and geniuses are, they’re a whole lot like the rest of us—and not immune to the same foibles. Sure, it’s nice to dwell on the positive. But in these times, I can’t help wishing for a companion volume to How Lincoln Learned to Read. Perhaps How Madoff Learned to Steal, or maybe How Greenspan Learned to Miscalculate.

* * *

Sarah L. Courteau is literary editor of The Wilson Quarterly.

Reviewed: How Lincoln Learned to Read: Twelve Great Americans and the Educations That Made Them by Daniel Wolff, Bloomsbury, 345 pp, 2009.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Up next in this issue