Spring 2010

Grandeur in Stone

– The Wilson Quarterly

The sculptors of the "American Renaissance."

The Civil War left both the North and the South bruised and battered, but the Industrial Revolution ensured that prosperity returned fairly quickly. Soon enough, the search was on for a culture appropriate to a rejuvenated America’s growing role on the world stage. Thus dawned the American Renaissance, a period when “art was at the heart of American civic life,” writes James F. Cooper, editor and publisher of American Arts Quarterly.

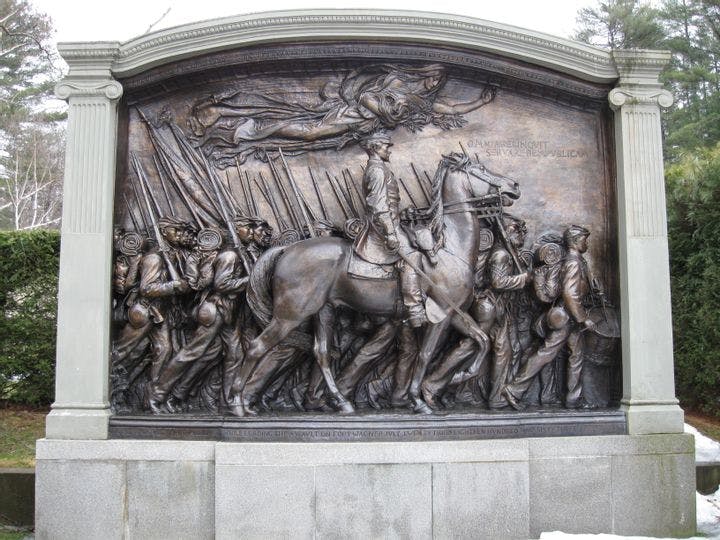

Augustus Saint- Gaudens and Daniel Chester French, arguably two of America’s greatest sculptors, exemplified the period’s mix of mastery, ambition, and gravitas. French is best known for Lincoln, the 19-foot-tall statue of the 16th president that sits inside the grand memorial on the National Mall, while Saint-Gaudens won praise for accomplished memorials to contemporary luminaries such as Robert Gould Shaw, the Civil War colonel who commanded one of the U.S. military’s first black regiments, and Navy admiral David Glasgow Farragut. Both sculptors were inspired by the moral authority and aesthetic excellence of Greco-Roman sculpture. But they also had unique strengths and influences.

Of the two men’s work, French’s was more traditionally neoclassical. He was particularly concerned with shape and form; like Michelangelo’s, French’s sculptures change “as one moves from one side to the other, each angle carefully composed for the benefit of the eye,” Cooper writes. Take Memory, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The sculpture is of a young, melancholy woman gazing into an indirectly angled hand mirror; “the seated figure is twisted gracefully in contrapposto . . . presenting perfectly composed compositions viewed from any angle.” French’s “Romantic passion and robust talent” made his work particularly powerful, Cooper writes.

Saint-Gaudens trained at the École des Beaux- Arts in Paris, where he was influenced by Modernism, which was then coming into vogue. In contrast to French’s classical style, which aimed to portray an idealized image of a subject, Saint-Gaudens’ approach is “realistic and naturalistic, intended to reveal the character of the sitter.” Indeed, Saint-Gaudens’ work, such as the bust of Abraham Lincoln with his bow tie charmingly askew, aim more for psychological realism than geometric harmony. “Mere physical beauty would detract from the spiritual essence he was seeking,” Cooper writes of a memorial Saint-Gaudens crafted to historian Henry Adams’s wife, Marian Hooper Adams, who committed suicide. Instead, Saint-Gaudens’ work “has a soul.”

Neoclassicism fell out of favor ahead of World War I, as artists grew enamored of the possibilities of abstraction. Many remarkable American Renaissance monuments were even destroyed. The reputations of French and Saint-Gaudens were spared such a drastic fate, but as men who “created great works that spoke to the nation,” Cooper believes, they are still woefully underappreciated.

* * *

The Source: "Sculptors of the American Renaissance: Augustus-Saint Gaudens and Daniel Chester French" by James F. Cooper, in American Arts Quarterly, Fall 2009.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Nitya & Jesse Eisenheim