Spring 2015

What We Talk About When We Talk About Selma

– Rebecca White

In Selma, there's a tangible sense of regret at how little the 50th anniversary celebrations had to do with the people who actually live there.

JUST HOURS AFTER PRESIDENT OBAMA SPOKE at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, an odd mixture of locals, tourists, press, and glossy-looking politicians converged downtown on Washington Street. Waist-high metal barricades blocked the street like a sieve, making sure only the credentialed few could roam as they wished through the high-security checkpoint.

As the day’s main events tapered down, rumors spread that the presidential motorcade would soon be driving out of town via Washington Street. Adults straddled the barricades, taking photos of every black SUV that passed by. Their children spent the time squeezing between the fence bars, bored.

Stephen Colbert was not restricted by the barricade. Among the honorary few with pre-approved press passes or recognizable names, he moved freely around town. In the hot, late-afternoon sun on this first Saturday of March, Colbert breezed past boxy men in uniform wearing coiled earpieces. He nonchalantly spoke into his cell phone and stopped to occasionally pose for pictures with his fans.

Colbert doesn’t live in Selma. Neither does the Reverend Al Sharpton, who was crisply dressed that afternoon and was escorted by an entourage that seemed attached to his presence like orbiting moons. When he walked down Washington, he strode toward his car with purpose. Unlike Colbert, he dodged fans and press alike.

Across town, a longtime Selma resident (who didn't want his name published) steered clear of the crowds, the street fairs, and the posturing — including a spirited sermon by Sharpton at the Brown Chapel AME Church on Sunday, where the reverend challenged the hagiographic praise of the generation of black Americans who came of age during the civil rights movement. “There were many people in the … generation who were not in the movement,” Sharpton said. “Just ‘cause you are old don’t mean we owe you no gratitude today.”

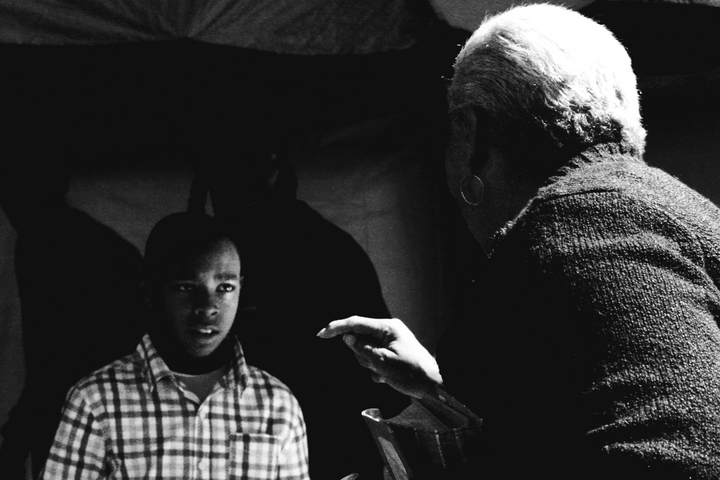

“I don’t want to hear that bullshit,” the longtime local told me as we walked around Selma's Seventh Ward, with an undercurrent of regret at how little the celebrations that weekend had to do with the actual people of the town, and how much the focus instead was on Selma as a staging ground. “There’s a lot of people in the shadows during the sixties that don’t want the limelight or the public. They did things from their heart to achieve voting rights.”

He requested that I not publish his name for fear of repercussions — not that he believes anyone will hurt him for voicing his opinion. A black man with many friends in his neighborhood, he wants to keep his reputation in tact.

His feelings of resentment are easy to understand. “You see what I see?” He nodded slowly toward a row of abandoned houses, their roofs caving in, some windows boarded up, some open, brandishing shards of unkempt glass.

“Welcome to Selma in 2015.”

Abandoned houses. Roofs caving in. Joblessness twice the state average. Welcome to Selma in 2015.

.png)

IN A TOWN OF ABOUT 20,000, Colbert and Sharpton joined tens of thousands of visitors for the commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” the violent confrontation on March 7, 1965, when peaceful civil rights marchers, planning a trek from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery in support of voting rights, crossed Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge and were met with baton-wielding Alabama state troopers — their ranks bolstered after an open call from County Sheriff Jim Clark, who, preparing for a melee, promised to deputize all the county’s white men over age 21. After armoring themselves with gas masks, the troopers shot tear gas canisters into the crowd and charged forward, some on horseback, nightsticks drawn, and rained blows upon the civil rights activists, injuring nearly 70 and aborting the march. Two weeks later, after the horrors of Bloody Sunday shocked many across the nation into action, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., successfully led a 54 mile march from Selma to Montgomery.

These demonstrations — and the public attention they drew — led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which forbade Jim Crow-era literacy tests and poll taxes. At the 50th anniversary commemorations, Attorney General Eric Holder and Reverends Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton (among others) drew attention to the 2013 Supreme Court ruling in Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, which struck down the preclearance requirement in the Voting Rights Act. Preclearance required certain jurisdictions — nine states, and dozens of counties and cities throughout the country — with histories of institutional discrimination and disenfranchisement to get preclearance from the federal government before changing their voting laws.

Though the public memory of Selma’s importance arguably never diminished, it roared back into the collective consciousness earlier this year with the release of the popular film “Selma,” a dramatized history of the events of 1965. Controversies haunted the film, from the ire of some historians and Lyndon Johnson partisans who felt that the film unfairly maligned LBJ, to — more notably — the film’s failure to gain nominations in most of the major Oscar categories. While the movie was a finalist for four Golden Globes, and though it received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture (and won Best Original Song), “Selma” missed out on nominations in other major categories where awards prognosticators had considered it a major contender, including nods for Best Actor (David Oyelowo for his portrayal of King) and Best Director (filmmaker Ava DuVurnay would’ve been the first black woman in Academy history to receive a nomination for directing). In light of the renewed, broader media conversation about race in American life, many in the media framed the slights as signs of persistent, yet implicit, veiled racism. Some even referred to this year’s Oscars as the “whitest” yet.

The anniversary seemed both to squelch and inflame sentiments about continued racial inequality, as if the movie, the civil rights movement, and anger over the police killings of Ferguson’s Michael Brown, New York’s Eric Garner, and 12-year-old Clevelander Tamir Rice — to name just a few — were all hoisted onto the shoulders of Selma, additional crosses for the city to bare.

Thoroughly reported on by national media upon their return to the town are Selma’s decrepit swaths of low-income neighborhoods, its unemployment rates (double the Alabama average), and the enduring segregation of its schools and churches.

Selma itself has, for better or for worse, become a symbol of the oft-repeated need for a “national conversation about race,” in lieu of major progress toward fixing the issues actually facing the town — or country, for that matter. The issues themselves, heavy and charged, may have overpowered the everyday concerns of regular people who may consider themselves foot soldiers in the fight for justice and equality, but live against the daily backdrop of joblessness, poverty, and crime.

It’s a local example of what may be a true, pervasive problem we face today as a nation. Everyone's pointing a finger, but they're all pointing them in different directions, and the cost of this lack of cohesion can be felt, regardless of its cause.

National leaders descended on Selma for anniversary speeches. “I don’t want to hear that bullshit,” a longtime local said as we walked around the Seventh Ward. There’s a tangible sense of regret at how little the anniversary celebrations in Selma had to do with the people who actually live there.

Explore a forgotten civil rights hero at Narratively: “The Brave and Tragic Tale of Reverend Turner”

THE COVER OF THE MARCH 8 Selma Times-Journal showed a heroic-looking President Obama in front of an American flag (a photo taken during his speech one day earlier). Below the image, a headline reads “History Honored.” Selma's newspaper dates back to 1827 and still prints six days a week, an honorable output, especially for such a small press. Locally, however, some people didn’t hold the paper in high regard. Several residents rolled their eyes when the newspaper was mentioned, saying that it does little to address Selma’s actual concerns, and instead resorts to knee-jerk civic boosterism where serious reporting is needed.

Pointing to the dilapidated Boynton House Museum, where legendary civil rights leader Amelia Boynton Robinson, now 103 years old, once lived, Selma Deputy Sheriff James Martin, 48, tried to verbally untangle the area’s struggles. “People have pretty much forgotten their past,” he said, drawing attention to the boarded-up museum’s chipping yellow paint, its faded welcome sign. The small Seventh Ward house is falling apart. “A lot of people don’t know that Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., himself slept on the floor of that particular house during the movement.” In earlier times, other visitors included John Lewis, Robert Kennedy, Nobel laureate Ralph Bunche, Andrew Young, Dick Gregory, Joan Baez, and Duke Ellington.

Deputy Sheriff Martin said the museum’s neighborhood has at least 16 structures that should be razed. He finds this neglect abhorrent, given what the area has done for the civil rights movement.

He pointed out that close to where he stood, near the Boynton Museum, is the Tabernacle Baptist Church, where large civil rights march organizing meetings took place in the sixties. A few blocks to the north is Selma University, which, founded in the Reconstruction Era, is one of the nation’s oldest historically black college and universities.

“The reason that this area is concentrated with such history is because this has always been the ‘black’ part of town, so of course they couldn’t go anywhere else,” Martin said. “The poverty is pretty much like any town in the United States, but the thing that made Selma so unique is because of the contribution that she has made to the nation as a whole.”

The poverty is pretty much like any town in the United States, but the thing that makes Selma unique is the contribution it has made to the nation as a whole.

ON THE ANNIVERSARY WEEKEND, Johnnie McWilliams, 80, was seated on his porch as the sun set on Martin Luther King Street. Behind him, written on the house’s siding in large black letters was “God is more handsome than the sons of men.”

“My daughter wrote that,” McWilliams said slowly, his voice trailing off as if slipping into memories. As he looked into the distance, I asked him about life in Selma. He spoke of slavery. “Sometimes, you dream about that, you know? What you think comes through your mind all the time. When you look at how you live.”

The scripture on his house lent itself to talk of the churches. “When the blacks, when they go to the white church, they turn around and you see them look at you like they don’t want you around,” McWilliams said.

The Selma Community Church is the only fully integrated house of worship in town, said congregant Kylie Jones. Jones, 25, is a white law student who moved to Selma from Colorado when she was 18. Early on the Sunday morning after the president’s speech, members of the congregation marched to protest a memorial to Confederate general and early Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest in a nearby cemetery. It was erected in 2000, and in March 2012, someone stole the bronze bust of Forrest from atop a marble pedestal. The marker has a Confederate flag engraved on it, and praises the general-turned-grand wizard as the “Defender of Selma.”

“They’ve roped off the memorial,” Jones told me that Sunday afternoon. “We found out this morning that they have blocked us from getting inside.”

Tensions unevenly felt, Selma resident Francine Smith walked coolly through town with her daughter, her son-in-law, and her grandson on Saturday after the president spoke. Smith, who works in a doctor’s office, is black, and her son-in-law is white. Her daughter and son-in-law met when they were in the military, and were both stationed on the same ship.

“I think when you say ‘Selma,’ they say, ‘Oh my God. Selma,’” said Smith, who believes that the town is far from being the divided battlefield people remember. She stayed firm as I pressed her on Selma’s residual racism.

“It’s not like that, it’s not like that,” Smith said, shaking her head. “In order for Selma to progress, then that stigma that’s being thrown on us has to be lifted so we can move on.”

* * *

Rebecca White is an Editor-at-Large for Narratively, as well as a regular contributor to the publication. Her work has appeared in such outlets as The New York Times and Al Jazeera America, among others. You can follow Rebecca on Twitter at @RebeccaWhiteNY, or on Instagram at @rebeccamariewhite.

This piece was produced in partnership between The Wilson Quarterly and Narratively.