Summer 2008

Humanitarian Dilemmas

– G. Pascal Zachary

The rapid expansion of relief efforts since the end of the Cold War has produced a surprising result: a series of difficult moral questions about the humanitarian enterprise.

In January, as I sipped a cool Nile Special in far northern Uganda, I watched a group of U.S. Army soldiers file into the open-air bar where I sat. They were not in uniform, but their bearing and speech gave them away.

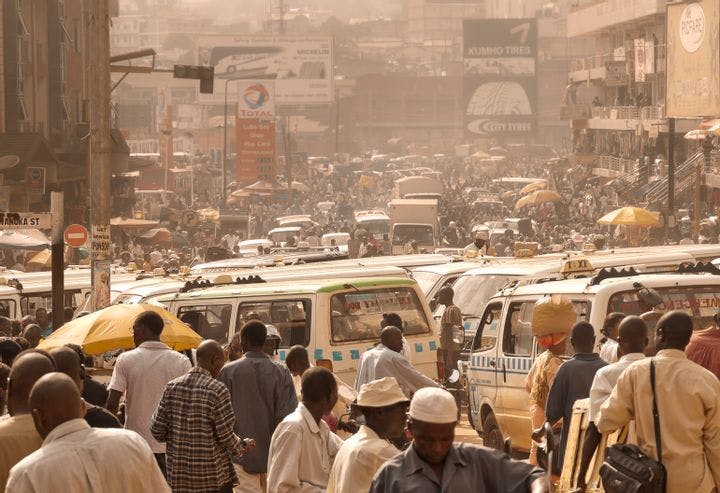

We were in a poor, dusty town named Gulu, eight hours by bus from the capital, Kampala. Night was falling, and as the soldiers ordered local beers, I wondered where they came from. Then I did a simple calculation. By helicopter, these troops could reach Garamba National Park in neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in roughly 30 minutes. There, in the jungle, Joseph Kony, Africa’s most notorious war criminal, was hiding.

Over the last 20 years, Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army have abducted tens of thousands of children in Uganda and killed or raped untold numbers of adults, most of them members of his own Acholi ethnic group. At the peak of Kony’s power, several years ago, nearly two million Acholi cowered in refugee camps, dependent on international aid organizations for sustenance. Uganda’s army has been unable—and, some critics insist, unwilling—to kill or capture Kony. Though the International Criminal Court has indicted Kony for crimes against humanity, it has no means of apprehending him.

In a single Rambo-like sweep, these American soldiers could end Kony’s reign of terror. I wondered if I had stumbled onto the scoop of my life.

As it happened, I was in the bar to meet the highest-ranking U.S. official posted in Gulu. A few minutes later, Christine turned up and ordered passion juice, a local favorite. I asked her if the Americans in the bar were soldiers.

She said they were from the Pentagon’s new African command in Djibouti.

My mind flashed to a threat reportedly made last year by the U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs. On a visit to Kampala, Jendayi E. Frazer is said to have told Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni that his army had three months to finish Kony off once and for all—or the United States might send its own soldiers to do the job.

“Are they here to get Joseph Kony?” I asked.

Christine started to laugh.

“They are animal doctors, livestock specialists,” she said. “They are here to vaccinate cows against diseases.”

“You’re joking.”

“I’m serious. Go ahead. Ask them.”

Yes, they said, they were on a humanitarian mission to inoculate local Ankole cattle.

“So you’re sticking to your cover story,” I said skeptically. The soldiers laughed. Then one rolled up a pant leg to expose a big, black bruise. “I got kicked in the leg today,” he said.

A comrade added, “African cows are dangerous.”

I wished the soldiers were lying, but they weren’t. Armed humanitarian intervention is still rare. American airpower helped put an end to ethnic cleansing in Kosovo in 1999, and the United States has intervened in Haiti and elsewhere. Leaning partly on humanitarian arguments, the United States has overthrown hostile governments in Iraq and Afghanistan. In Africa, however, U.S. soldiers don’t start wars—or end them. Instead, U.S. tax dollars, along with funds from foreign donors and private charities such as World Vision, Catholic Relief Services, and the American Refugee Committee, are devoted to another kind of humanitarian intervention, aimed at relieving the suffering of people trapped in war zones or, as in Zimbabwe, under the calamitous rule of bad governments.

The outsiders come with good intentions and do the best they can. In the DRC, United Nations troops and aid workers have struggled without success to bring stability for 10 years. The people of Somalia, Liberia, and Sierra Leone have endured incredible suffering. And there is the tortured Darfur region of Sudan, where, after five years, more than 2.5 million displaced people still live amid a widening civil war and government-organized predations that have rendered everyday life a kind of nightmare. In response to the horror in Sudan, humanitarians cannot simply organize the overthrow of the government; nor are donors willing to embark on a long-term reconstruction (and occupation) of that vast country. The humanitarians’ only recourse is to try to relieve the suffering of millions of people—often at some peril to themselves. In Somalia, for example, Islamist insurgents have abducted several UN relief workers, including, in late June, the head of UN refugee efforts in Mogadishu.

But as humanitarian organizations have increasingly discovered, even their neutral efforts to help can alter conditions on the ground in unexpected ways. This unpleasant truth became apparent to me in 2000 when a journalistic assignment took me to Burundi, in central Africa. The government was battling an ethnic insurgency in the mountains around the capital, Bujumbura. In order to reduce support for the insurgents, the government forcibly removed thousands of people from the area, emptying whole villages and ordering the inhabitants to move to open ground, where government soldiers could better prevent them from helping the rebels.

The tactic, a classic of counterinsurgency, created a humanitarian crisis. But not for the government. It summoned private groups and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the UN’s refugee agency, to deal with the displaced people. Even though they knew that the government itself was responsible for the disaster, the humanitarians came, wallets open.

I remember visiting a makeshift refugee camp with the country director of Catholic Relief Services, a leading humanitarian agency. Thousands of people were spread over the side of a hill, protected from the rains by tarpaulins provided by CRS. As we toured the camp, we were followed by armed Burundian soldiers. The director, a fellow American, was glad to see his tarps being put to good use. But I got angry thinking that CRS was essentially helping the government carry on its war.

“You’re making it cheaper for the government to mistreat its own people,” I barked.

As if he’d heard such reactions before, the CRS man smiled wanly and put his arm around me. “It’s the only choice we have,” he said. “Without us, the people suffer more.”

Our eyes met, and I saw his sincerity. “Where do you draw the line?” I whispered. “When do you walk away?”

Humanitarians themselves are increasingly asking such questions. “Even stalwart defenders of humanitarianism concede that the moral necessity of humanitarian action is no longer self-evident,” write Michael Barnett and Thomas G. Weiss in their introduction to a new collection of essays, Humanitarianism in Question: Politics, Power, Ethics. Humanitarianism, they say, “is in the midst of a full-blown identity crisis.”

That identity crisis comes after two decades of rapid growth in the humanitarian enterprise. Modern humanitarianism originated in British abolitionists’ successful campaign against slavery in the first half of the 19th century and the creation of the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1863–64, and it grew in fits and starts through the 20th century. The end of the Cold War brought a vigorous new phase of growth, driven by government and private actors alike, resulting in a large and sophisticated network of humanitarian efforts that Alex de Waal of Harvard’s Global Equity Initiative calls the “humanitarian international.” And just as the creation of the U.S. defense establishment after World War II spawned a new breed of defense intellectuals, so the rise of de Waal’s “international” has fostered a new generation of humanitarian intellectuals who concern themselves with the movement’s moral and operational conundrums. Barnett and Weiss, political scientists at the University of Minnesota and the City University of New York Graduate Center, respectively, describe some of the questions that engage the intellectuals, as well as many of their counterparts in the field:

When, if ever, should [humanitarians] request armed protection and work with states? Would armed protection facilitate access or create the impression that aid workers were now one of the warring parties? Should they provide aid unconditionally? What if doing so means feeding the armies, militias, and killers who are responsible for and clearly benefit from terrorizing civilian populations? At what point should aid workers withdraw because the situation is too dangerous? Can aid really make a difference?

Yet for all the pitfalls of humanitarian efforts, it is also clear that staying the course can sometimes pay off. In the summer of 2000, shortly after my trip to Burundi, I traveled to Kosovo, the breakaway Yugoslavian province where a Serb campaign of ethnic cleansing had been halted only by a U.S.-led NATO military intervention in 1999. I went there to visit a refugee family that I had literally followed around Europe during the previous year. I’d first met the Hajdaris in a Macedonian refugee camp. When that temporary haven was hurriedly dismantled amid NATO preparations for a planned assault on Serbia, the family had been moved to Britain, and I caught up with them at their new home in the village of Ulverston, where they bubbled with news that their 13-year-old daughter, Arijeta, got to shake Queen Elizabeth’s hand and thank her in rudimentary English for her country’s generosity. Now, having returned to Kosovo, the Hajdaris had resumed life in their village, Livoç i Poshtëm, where U.S. Army troops guarded the peace. The family, which had been driven out when Serbs burned their home down, returned specifically because of the security provided by the American soldiers. The village still consisted of a mix of Christian Serbs and ethnic Albanian Muslims, and relations were tense.

The American soldiers kept order through the force of their guns, determination, and discipline. The human benefits were clear. One morning, I walked with Arijeta to her school and quietly observed her in a math class. She sat in her usual chair in the first row, surrounded by four other girls, all of them whispering together and laughing. When the teacher arrived, Arijeta was the first to stand to attention. After school, she took me on a tour of her village and, no longer smiling, told me, “This is the house of the Serbs who burned down our house.”

The Hajdaris wanted to take revenge, but the American soldiers aimed to prevent that, too. In a goodwill gesture, a soldier one day gave Arijeta’s younger brother, Leontiff, a soccer ball. “Americans—good,” the boy said as we kicked the ball around.

The next day, I walked with members of a U.S. Army platoon as they escorted dozens of Serbian children to an elementary school. “We don’t take sides,” a soldier from New Jersey said. A Serb parent commented that without the American troops, “we would not feel safe and we would start fighting again.”

In the nine years since NATO intervened in Kosovo, sub-Saharan Africa has increasingly become the focus of the world’s humanitarian efforts. Two centuries ago, it was because of Africa that humanitarians launched their first major campaign of modern times, resulting in the abolition of the slave trade in the British Atlantic in 1807 and the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833. Today, sub-Saharan Africa is home to more humanitarian crises than any other region in the world. And these crises also seem to last longer, and require more resources, than any other. Seven UN peacekeeping operations are currently under way in sub-Saharan Africa, including one in the DRC that began in 1999. The total for the rest of the world is 10.

Giving help to distant Africans can be a perilous undertaking. Somalia and Rwanda taught us that. In Somalia, the United States failed in 1993 to halt a civil war; the image of dead American soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu remains a grim rejoinder to anyone who might advise sending combat troops into an African war. The following year, when Hutus fell upon Tutsis in Rwanda, the world stood by and watched as nearly one million people were killed in a genocidal slaughter. But what shook the confidence of humanitarian groups even more deeply than the failure to halt the Rwandan genocide was the aftermath, when a Tutsi guerilla army led by Paul Kagame took over the government and ignited a mass exodus of Hutus. The international community responded with aid for the Hutus who sought refuge at camps in the DRC, but the camps became havens for Hutu killers, who used them to stage fresh attacks on Tutsis in Rwanda. “Many aid workers were shaken, demoralized, and haunted by their experience in Rwanda where their aid prolonged the suffering of those in the camps that were controlled by the [Hutu] genocidaires,” write Barnett and another coauthor, Columbia political scientist Jack Snyder. “Aid workers want to know how they can do their jobs better and how to make the most of their limited resources.”

Out of the Rwandan crackup came demands for a more robust, self-critical, and efficiency-minded humanitarianism that pledged, in the words of Mary Anderson, a leading practitioner, to “do no harm.” In a 1999 book with those words as a title, Anderson bluntly concluded, “Aid too often also feeds into, reinforces, and prolongs conflicts.” Another response to Rwanda has been the evolution of humanitarian codes and protocols, some of which are quite elaborate, even daunting, in their complexity. In some quarters, the high-minded do-gooder of the past has come to be seen as a throwback, or even a hazard. “Humanitarian assistance, particularly in the midst of conflicts and disasters, is not a field for amateurs,” argues Kevin M. Cahill, director of Fordham University’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs, in Basics of International Humanitarian Missions (2002). “Good intentions are a common but tragically inadequate substitute for well-planned, efficiently implemented operations that, like a good sentence, must have a beginning, a middle, and an end.”

Even as they confront the tension between their traditional mission to do good and the need to think about all manner of unintended consequences, humanitarians are also weighing a third element: tackling the root causes of humanitarian crises, and delivering the sort of aid that might provide durable “insurance” against them.

There is an undeniable logic to this kind of approach, but when they try to address long-term needs, humanitarian organizations cross over into the field of development assistance—and risk not only losing their focus and effectiveness but blundering into new minefields.

Norbert Mao understands the promise and perils of modern humanitarianism as well as anybody on the planet. Mao is an Acholi (the group has a taste for bestowing the names of famous people on their children) who lives in Gulu. At 41, he is the highest elected official in Gulu District and the most influential elected official in northern Uganda, as well as a leader of a national opposition party. Among foreign diplomats Mao is universally respected, and with the help of the U.S. government he recently spent an academic year at Yale University. I first met him late one night in the same bar where I encountered the American soldiers. Mao said he had supported the new wave of assistance that began to arrive in 2004 after the United Nations declared the situation in northern Uganda one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. “Relief was necessary, but these relief efforts now need to be scaled down,” he said. The foreigners had overstayed their welcome and, without any sanction from local authorities, had created a parallel government that is accountable to no one, cripples self-reliance, and fosters Acholi dependence on handouts.

Mao’s complaints were partly self-serving, since failures by all branches of the Ugandan government had given rise to the need for outside aid in the first place. But Mao justifiably complained about the sanctimony often displayed by individual aid workers—“disaster tourists,” he called them—and their insensitivity toward the culture of his conservative, patriarchal society. He bristled over their interference in matters that go well beyond emergency relief. He has tangled frequently with the American Refugee Committee, which has taken on the mission of providing refuge to abused wives. Mao argued that the humanitarian groups “are embracing a new agenda simply to stay relevant.” He said he held 15 or more meetings a week with international aid agencies just to stay abreast of what they were doing.

The shooting war has ended in northern Uganda, and so has the need for urgent relief, yet the development requirements of the region are huge. The Lord’s Resistance Army hasn’t mounted any attacks in nearly two years; Joseph Kony’s long-time sponsor, the government of Sudan, has cut off its support. By any measure, northern Uganda is now safer than many parts of the United States. But the region’s people live in a peculiar limbo, a condition that James Nyeko, leader of a local interfaith council, has described as “no peace, no war.” Efforts to end the lingering threat posed by Kony have repeatedly failed. The Ugandan army, which had little trouble striking deep into the DRC in an orgy of looting in the 1990s, has proved strangely unable to dispatch the ragtag remnant of Kony’s forces. Peace negotiations have dragged on inconclusively since 1993. Not surprisingly, many observers have concluded that the prospect of losing the humanitarians’ largesse has left the government less than eager to end the conflict.

The rebels, too, have incentives to stop short of peace. In Uganda, as in other cases, they can steal humanitarian aid, impose a “tax” on recipients, or, in some instances, receive aid directly. The negotiators for the Lord’s Resistance Army receive direct financial support from European donors, including a per diem allowance for days spent representing Kony (who gets a kickback) in peace talks. (And aid givers aiming at “root causes” of violence and rebellion, such as poverty, sometimes essentially reward insurgents for taking up arms.)

Other pathologies are less obvious. Because the end of war means an end to food, housing, and other foreign assistance, requests for post-conflict aid often become a stumbling block in negotiations in places such as Uganda. Not only do combatants demand money to lay down their arms and start a new life, but people who live in refugee camps often expect cash “buyouts” to return to their original homes—after all, they are giving up a number of benefits.

At first blush, Zimbabwe would seem to present fewer complexities and traps for well-intentioned outsiders than Uganda. Aid agencies have for years been providing food and medical relief to poor people in the southern African country, where economic and social conditions have steadily deteriorated. The agencies have scrupulously avoided politics and any overt concern for the longer-term future of Zimbabwe in order to avoid running afoul of the country’s president-cum-dictator, Robert Mugabe. The posture of one prominent agency, World Vision, which says it helps meet the basic human needs of one million Zimbabweans per month, or nearly 10 percent of the population, is typical. By “maintaining minimal activities in the field and sticking to activities that have little ‘community mobilization,’” World Vision says it has steered clear of anything remotely threatening to Mugabe’s government.

Yet even this very narrow dedication to the immediate relief of suffering has proved unsustainable. This past June, on the eve of the country’s bitterly contested but eventually derailed presidential runoff election, Mugabe shut down all aid operations, claiming they were strengthening his political opponents. While Westerners bemoaned Mugabe’s step, Zimbabwean dissidents presented a more nuanced interpretation. They insisted that Mugabe’s government had long manipulated the “humanitarian international,” steering donated food and other goods to supporters of the regime. In one widely reported example this year, the government seized a truck loaded with 20 tons of American wheat and pinto beans destined for poor schoolchildren and blatantly gave the food to Mugabe supporters. Good intentions, in short, were exploited to strengthen Mugabe’s repressive regime.

“Zimbabwe is a huge patronage system, and ZANU-PF [Mugabe’s political party] drives that system,” Eldred Masunungure, a political scientist at the University of Zimbabwe, told The New York Times. “Food distribution is not only a matter of life and death to recipients, but it’s a strategic political resource that the government deploys to promote its political agenda.”

In order to succeed, humanitarian efforts require a “Goldilocks” solution—just the right mix of force and charity, sympathy and structure, blind will and determined follow-up. Getting that mix right, as in Kosovo, is difficult but not impossible. Some measure of military support can help some of the time. In Francophone West Africa, France’s military forces often intervene to bolster failing states or halt civil wars. Earlier this year, the government of Chad—nobody’s idea of a model regime—was kept in power by a timely threat by French forces, which happen to have a permanent base in the country. A few years before that, in Côte d’Ivoire, French troops intervened in a civil war between the Muslim North and Christian South. While the willingness of the French government to send troops into Africa violates—or obliterates—the sovereignty of these countries, there is a humanitarian benefit. In Francophone Africa, there is a distinctly lower incidence of humanitarian crises. One can argue that the French end up keeping bad governments in power, such as Paul Biya’s in Cameroon and Omar Bongo’s in Gabon, but they prevent the sort of barbaric disorder that has engulfed Somalia, Sudan, and parts of Congo.

The lesson is not that military intervention per se prevents humanitarian disasters but that—notably in Africa—the intervention of soldiers from a single powerful country equipped with extensive local knowledge, often acting unilaterally, can decisively reduce the incidence and severity of humanitarian crises.

Yet timing military interventions is something of a crapshoot, and there is no science to choosing opportunities. The best results, again, seem to involve former colonial armies in Africa. Elsewhere in the world—notably Iraq and Afghanistan—military intervention designed to bring about regime change, and done partly in the name of reducing human suffering, can have the opposite effect. Of course, many humanitarian crises don’t permit even the remote possibility of a military response. When Myanmar’s ruling junta made it all but impossible for outsiders to help the victims of a devastating cyclone and tidal wave earlier this year, there were scattered calls in the West for using force to get aid into the country, but there was little prospect of action. Despite efforts to chip away at the concept of national sovereignty—a UN summit in 2005 endorsed the principle that outsiders have a “responsibility to protect” people facing certain kinds of threats, regardless of national borders—sovereignty remains alive and well in the real world. Many developing countries regard the new principle as a thinly veiled effort by the West to find a way to impose its values on them, and, in any event, it is rare that many nations can be rallied to a risky and expensive cause in which they have no direct interest. The continuing ability of nation-states to chart distinct courses guarantees that humanitarianism will often be simply an exercise in providing Band-Aids for grievous and painfully lingering wounds.

Humanitarians will continue to need patience and a willingness to make the best of bad situations. Even in Kosovo, where humanitarians were backed by military force and worked under conditions of relative peace and security, billions of dollars were required to help a relatively small number of people and still for a long time it appeared that the state of political and social limbo might last forever. In northern Uganda, however, the perverse incentives of humanitarian assistance may be merely prolonging a stalemate. Still, the limbo of dependency and interference in local affairs by the “humanitarian international” is much preferable to the resumption of war.

The Goldilocks solution is unsatisfying to scholars and many practitioners, since it acknowledges that we don’t know what is working until after it has been done. Purists who don’t want humanitarian aid to help the Mugabes and Konys of the world, either directly or indirectly, can’t be happy with the Goldilocks solution either. And those who wish humanitarian aid to tackle long-term problems and root causes—in essence, to serve legitimate development aims—will also be disappointed. As a practical matter, the relief of suffering is an achievement that can be measured day by day, while creating sustainable benefits and structural changes in societies can only be judged over long periods of time.

Whatever its shortcomings, the Goldilocks solution—getting humanitarian intervention just right—cannot be judged on measurable outcomes alone. Humanitarianism is ultimately about our humanity: how we choose to live. Good intentions are not enough, but they are still something.

A couple of months ago, I was reminded of how much the purely human aspect of humanitarianism matters when I received an e-mail from Arijeta Hajdari. I’d not heard from her or her family for years. Coincidentally, her message arrived just days before Kosovo gained full sovereignty after nine years of UN rule. Arijeta wrote in halting English that her family was well. Her parents had, finally, a brandnew house to replace the one destroyed by the Serbs. Her brother, Leontiff, was studying architecture and still playing soccer. Arijeta herself was attending Kosovo’s leading university, in Pristina. She was 21 years old and studying criminology. She wanted to pursue a career in law-enforcement. Attached to her e-mail was a photograph of her with friends, dressed well, perhaps at a party. She was smiling.

She asked me about my son and daughter and whether I remembered how they played with her and Leontiff in the English town where she met the queen of England. And did I recall another time, she asked, when her family came to visit mine in London? And how the Hajdaris had stayed in our house, and we showed them around the city?

I wrote back to Arijeta and told her that, indeed, we all remembered the Hajdaris and were happy to learn they were well.

Minutes later, another e-mail came from Kosovo. “It is lovely to hear from you,” Arijeta wrote. “I thought that you had forgotten us.”

I have not.

* * *

G. Pascal Zachary is the author of Married to Africa, a memoir to be published by Scribner in January 2009. He is a former foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal and a consultant on African issues to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/weesam2010