Summer 2008

Yoknapatawpha Diplomacy

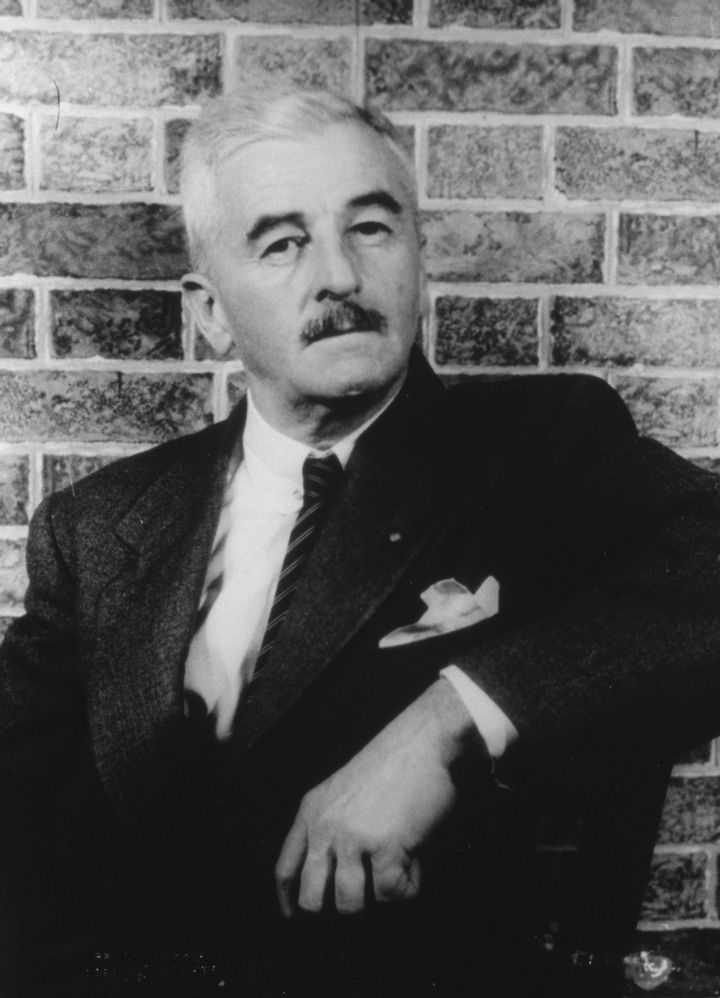

William Faulkner, a reclusive writer fond of drink, might seem a curious emissary to foster American goodwill abroad, but during the Cold War, artists and intellectuals were considered not only relevant but vital to U. S. foreign policy.

A half-century ago, during a period of particularly fervent anti-Americanism, the U.S. State Department launched a massive campaign, quaint by today’s standards, to win hearts and minds around the globe. At the height of the Cold War, America mobilized not seasoned diplomats and practiced public-relations specialists, but intellectuals. Nobel Prize–winning novelist William Faulkner was dispatched to South America.

Faulkner (1897–1962) was a curious emissary in a propaganda war. One of the world’s most reclusive celebrities, he had to be persuaded to attend his own Nobel Prize ceremony in Sweden in 1950. But as the Soviet Union filled the world canvas with portraits of a grossly materialistic America without cultural achievements, Faulkner responded to appeals to his patriotism and agreed to represent the United States internationally. Acclaimed as a writer earlier in Europe and South America than in his home country, Faulkner “fulfilled the wildest dreams and underlying political agenda” of the government that sent him, writes Deborah Cohn, a professor of Spanish literature at Indiana University.

He ran into a rough patch in Brazil on his first Latin America foray, in 1954, when he drank himself into a “pre-coma” state and was unable to participate in as many activities as the State Department had hoped, but redeemed himself with gracious press interviews on the rest of the trip. In 1961, on a tour to Venezuela, where Vice President Richard Nixon’s motorcade had been stoned three years earlier, Faulkner lectured, gave press conferences, and conversed with unsympathetic Marxist critics and pro-Soviet journalists as a “nonpolitical, modernist author who addressed ‘universal truths,’” Cohn says. A year later, when the National Guard was called in to enforce the desegregation of the University of Mississippi near his home, State Department officials noted in internal communications that he provided a counterbalance to Soviet efforts to define America as a land of bigotry and race riots.

The U.S. government’s enlistment of highbrow cultural figures in its “propaganda wars against Communism,” Cohn writes, was inspired by a belief that promoting greater understanding and respect between cultures would “ultimately benefit national security.” The years of the Cold War were heady times for American artists and intellectuals, when they were considered not only relevant but vital to U.S. foreign policy.

The public diplomacy of these figures took a sometimes unpredictable course. Faulkner’s travels in Latin America spurred interest in the works of Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez, and Mario Vargas Llosa in the United States. Thus, the effort to bestow the blessings of American literature on Latin America wound up enriching American border.

* * *

The Source: "Combating Anti-Americanism During the Cold War: Faulkner, the State Department, and Latin America" by Deborah Cohn, in The Mississippi Quarterly, Volume 59, No. 3.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons