Summer 2009

A Modern Problem

– Martin Walker

Reviewing a new study of Islam and the modern world.

Like many other disappointed politicians, Ali Allawi turned to the consolations of philosophy and religion. The result is a remarkably thoughtful and engaging assessment of the current state and future prospects of the world of Islam. Allawi is the nephew of the Iraqi exile leader Ahmed Chalabi, who was briefly the darling of Washington’s neoconservatives. When Chalabi returned to Iraq upon the toppling of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Allawi followed, leaving his life as an Oxford don to serve as minister of trade and defense and then as minister of finance in the first transition governments.

Chastened and disillusioned by the experience, Allawi is now a visiting fellow at Princeton. His 2007 book The Occupation of Iraq is by far the best descriptive analysis of the disasters that unfolded when American hopes met Iraqi realities. His new book joins the increasingly crowded debate over the fundamental question of whether Islam can be reconciled with the modern capitalist world.

His answer is a cautious and conditional “yes.” He believes that the capitalist West is being forced to change as its citizens recognize that environmental constraints have foreclosed the era of limitless material growth, and that personal ambition should operate within the broader context of the common good. “The rugged, autonomous individual so beloved by liberal philosophers and by Hollywood movies simply cannot exist outside the virtuous community,” he writes. “And Islam would add that neither the individual nor the society can be whole if they are not infused with the sense of the transcendent.”

But Islam has yet to reconcile with the better aspects of the post-Renaissance and post-Enlightenment West: intellectual freedom, the questioning of tradition, a commitment to education and the scientific method. Islam’s attempts to embrace modernity have taken false and essentially political paths, Allawi argues, whether through Arab nationalism, state socialism, the crazed jihadism of 9/11, or what he condemns as the “legal trickery” of so much modern Islamic finance (which allows some religious figures to line their pockets by certifying that particular investments comply with Islamic law). Allawi has little respect for “the Gulf countries’ exuberant embrace of a frantic hypermodernity only scantily garbed in Islamic idioms,” and even less for the anti-intellectual Wahhabism he blames for the implosion of Islamic cultural life and creativity.

Allawi overstates the deleterious effect of Wahhabism, which came along centuries after the Mongols and Tamerlane crushed the first great flowering of Islamic civilization. But he is right to point out disparities between what the Islamic world once was and what it is today. “The creative output of the 20 or 30 million Muslims of the Abbassid era [ad 750 to 1258] dwarfs the output of the nearly one-and-a-half billion Muslims of the modern era,” he comments sourly. The Muslim countries of the Organization of the Islamic Conference, a 57-member voting bloc in the United Nations, “have 8.5 scientists and technicians per 1,000 population, compared to a world average of 40.7 and a developed-world figure of 139.3.”

Allawi devotes much of the book to the intellectual civil war within Islamic theology, asking whether “a modern society, with all its complexities, institutions, and tensions, [can] be built on a vision of the divine.” He finds a possible answer in the work of Syed Naquib al-Attas. Born in 1931 in Java, al-Attas attended Sandhurst, the British military academy, and served as an officer in the Malay regiment before becoming a philosopher and teacher. He sought to create an institution to breed “the complete man, . . . a Muslim scholar who is universal in his outlook and is authoritative in several branches of related knowledge.” In Malaysia in 1987, he founded the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, which taught in English and quickly became an important center for a generation of Islamic scholars who questioned the traditional Arab dominance of Muslim thought.

But in 2004 al-Attas was forced to retire, and his school was merged into an Islamic university dominated by Saudi-funded rivals. Allawi sees al-Attas as a victim “of an ongoing war, within the world of higher education in Malaysia and the wider Muslim world, around the issue of the meaning of the Islamization of knowledge and of the functions and purposes of an Islamic university.” Behind the conflict lies the relentless drive of Wahhabists with unlimited funds who seek to dominate Islamic intellectual life with their tradition-based puritan approach. For Allawi, their mission represents “the closing of the Islamic mind.” Wahhabism’s triumph is not final, he concludes, but for the moment its success means that “the much-heralded Islamic ‘awakening’ of recent times will not be a prelude to the rebirth of an Islamic civilization; it will be another episode in its decline.”

* * *

Martin Walker is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and senior director of A.T. Kearney's Global Business Policy Council.

Reviewed: The Crisis of Islamic Civilization by Ali A. Allawi, Yale University Press, 304 pp, 2009.

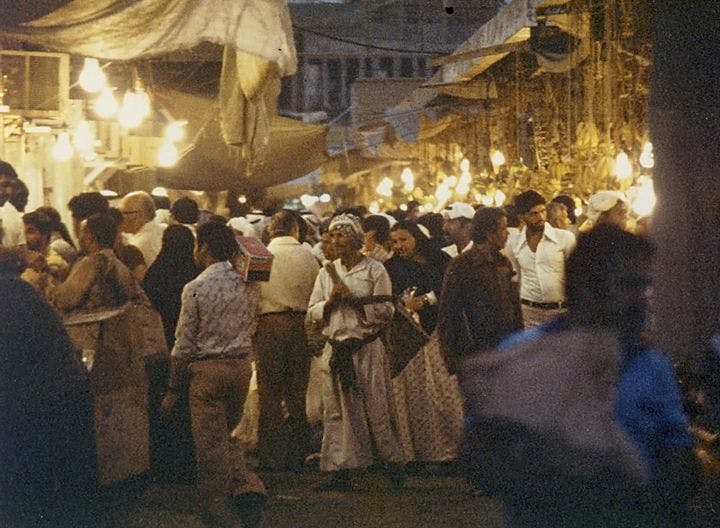

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Dennis S. Hurd

Up next in this issue