Summer 2009

Africa's Orphans

– The Wilson Quarterly

Clamping down on foreign adoptions seems to many African leaders like a relatively cost-free way to stand up to Uncle Sam.

To grasp the magnitude ofthe African AIDS crisis, imagine that all 11.6 million children living in the coastal states from Florida to Virginia had been orphaned by AIDS. In sub-Saharan Africa, this calamity is not hypothetical, it’s fact. And the HIV/AIDS crisis that affects more than 30 percent of the population in some of the nations of that region is beginning to deplete the “once seemingly limitless network of extended-family” members able to raise parentless children. Foreign adoptions are only beginning to take up the slack. Although American adoptions from Africa have become much more common since the 1990s, the number of children adopted in 2006 from the leading source country, Ethiopia, reached only 732.

Many African countries make it difficult for outsiders to adopt orphans. Openness to adoption is not determined by the severity of the orphan crisis, the prevalence of AIDS, or the level of democracy in the orphans’ homeland, write political scientists Marijke Breuning and John Ishiyama of the University of North Texas.

Clamping down on foreign adoptions seems to many African leaders like a relatively cost-free way to stand up to Uncle Sam.

Government officials are more likely to base their decisions on domestic politics, the authors say, and, because so many Africans fear “baby buying,” restrictions are easy to tighten. America accounts for about half of all intercountry adoptions worldwide. Clamping down on adoption seems to many leaders like a relatively cheap way to stand up to Uncle Sam. Frustrated with the meager benefits they net from globalization, African leaders are tempted to “frame intercountry adoption in terms of exploitation and to restrict or prohibit it.”

Malawi, with 12 percent of its adult population suffering from HIV/AIDS and an estimated 560,000 AIDS orphans, requires prospective parents (singer-actress Madonna excepted) to foster a child for two years in the country before adoption may occur. Other countries require in-country waiting periods of six months, or have no official agency responsible for approving legal procedures, or refuse to allow groups devoted to placing orphans overseas to operate on their territory.

The more closely an African nation is connected to the global economy (measured by the level of foreign investment), the more likely its government is to see the potential benefits of having some orphans find homes abroad. Such adoptions may cause adoptive parents to advocate and provide resources for improved social services in their child’s birth country. Thus, policy is driven by the expectation not only that orphans will find homes, but that they and their adoptive parents will become informal and unsuspecting “ambassadors of goodwill” between countries.

THE SOURCE: “The Politics of Intercountry Adoption: Explaining Variation in the Legal Requirements of Sub-Saharan African Countries” by Marijke Breuning and John Ishiyama, in Perspectives on Politics, March 2009

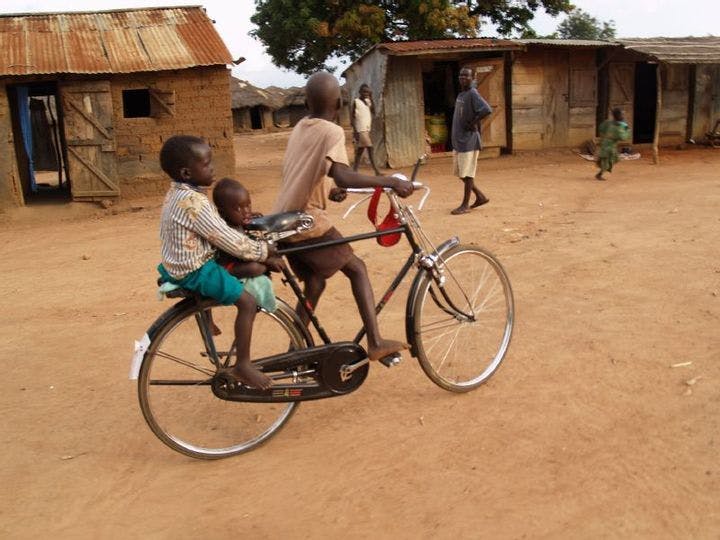

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Robin Yamaguchi