Summer 2009

Changing Tunes

– Grant Alden

The commercial revolution in American music.

Inventors ran wild during the years bracketing the turn of the 20th century, creating technology that repeatedly transformed the ways people heard and consumed music. It happened again a hundred years later, which makes David Suisman’s lucid account of the emergence and consolidation of the music industry particularly welcome.

Before the Industrial Revolution worked its magic, music was mostly an amateur (or at best semipro) affair, something one played and listened to in parlors, at dances and marches, in concert settings, and in vaudeville halls. Songs had been sold as sheet music throughout the 19th century, but the publishers—printers, really—were small, scattered businesses. That slowly changed, and by the 1890s sheet music publishers were competing fiercely for market share—for “hits”—paying song pluggers (the term survives) to sing and place songs with performers in every conceivable setting, from department stores to prisons. Thus began the process of injecting popular music into our daily lives, converting songs into commodities that were “unapologetically commercial and distinctively American.”

Naturally, such investments had to be protected, but not until the landmark Copyright Act of 1909 did U.S. law recognize something as intangible as a song as property. Suisman, an assistant professor of history at the University of Delaware (and a DJ on freeform independent radio station WFMU in Jersey City), does a first-rate job of sketching the publishers’ role in drafting that legislation. But he does not entirely sympathize with the impulses behind the law, which he views as “fetishizing the composer and the composition” rather than the performance, and granting preferred status to composed music over interpreted forms, such as traditional folk or jazz.

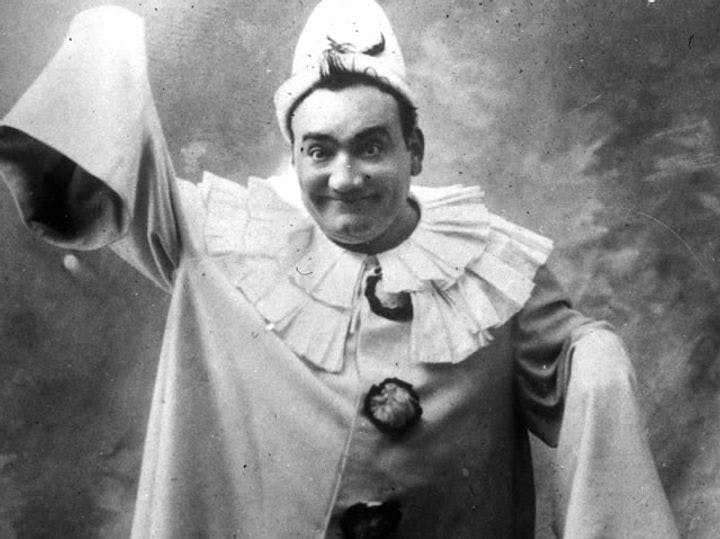

He describes the boom and bust of the industry that developed around the player piano, the most successful mechanical playback device (many variations on the music box were experimented with) to emerge before and compete with the phonograph. And he details the emergence of the Victor Talking Machine Company, founded in 1901, which produced both 78 rpm discs (burying Thomas Edison’s recorded cylinders) and the majority of the devices that made it possible for ordinary people to hear, say, the superstar tenor Enrico Caruso. Finally, in a curious counterpoint to Victor’s story, he traces the rise and fall of the African-American–owned Black Swan label, which sought to prosper while serving as an instrument of social change and artistic expression.

These stories, all well and carefully told, expand upon Suisman’s 2003 prize-winning doctoral dissertation. As there are few documents to analyze and no survivors to interview, he was obliged to rely on trade journal puffery, the papers of key figures such as gramophone inventor Emile Berliner, and, when discussing publishing firms, the songwriting manuals of the time. Throughout Selling Sounds there wafts a faint odor of disapproval, as if Suisman wishes things had gone differently. “On the one hand,” he writes, “the recording industry’s vast offerings could seem like a Whitmanesque celebration of the great plurality of talent in American life. On the other hand, fundamental to the industry’s development was the exploitation and reinforcement of cultural hierarchy.” What he means by that, exactly, never quite gets said, and that’s a pity, for it might well have led to a fine argument on both sides.

Suisman writes extensively about Victor’s aggressive and trendsetting marketing campaigns (the record company was the largest advertiser in the United States in 1923), and its highly effective efforts simultaneously to brand Caruso (signed to an exclusive contract in 1904) and its label. Only in passing does Suisman note that Victor’s elite Red Seal imprint was considerably outsold by its more pedestrian labels—whose catalogues included Tin Pan Alley’s plentiful offerings—and that Caruso made most of his fortune singing to the public, not recording for it.

As new technology makes the possession of songs ever more transitory, not to mention functionally free, working musicians are turning again to live performance as their principal income source. And consumers—some of whom have owned Beatles songs on 45s, eight-tracks, LPs, and CDs, and now as MP3 files and cell phone ringtones—are still mulling the costs and benefits of technology in delivering music to their ears.

* * *

Grant Alden was the founding coeditor and the art director of No Depression magazine.

Reviewed: Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music by David Suisman, Harvard University Press, 356 pp, 2009.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Floor

Up next in this issue