Summer 2011

Battle Over Britain

– Don H. Doyle

A century and a half ago, Britain was the world’s mightiest maritime power — which explains the harsh competition for its favor during the Civil War.

During the 1860s, the world watched with tremendous interest as the United States descended into a fratricidal war that seemed to doom the young country to fragmentation and prove the experiment in democratic self-government a failure. There were two conflicts: the land war and the diplomatic duel over the recognition of the Confederacy as a sovereign nation. British historian Amanda Foreman has written a splendid book that weaves the war in America together with the diplomatic contest in Britain, the most crucial foreign battle zone.

A century and a half ago, Britain was the world’s mightiest maritime power. It also possessed a large industrial economy that depended heavily on cotton from the South. The South’s fire-eaters dashed into secession confident that Britain would recognize the Confederacy’s independence and aid its struggle with loans, ships, and arms, perhaps even outright military intervention. This confidence derived not only from Britain’s economic interests but from Southerners’ knowledge that Britain feared that a “cotton famine” might ignite revolutionary social unrest among its workers. King Cotton “waves his scepter . . . over the island of Great Britain,” one of the secessionists boasted.

Britain’s government and its people were at odds over which side to support. Though the public was strongly antislavery, at the outset of the war it was not clear that the North intended to end the institution, nor that it had any higher moral purpose than to preserve national boundaries. Diplomats and propagandists for North and South worked diligently, often in secret, to persuade politicians, the press, and the public of the righteousness of their respective sides’ causes. Foreman deftly shifts among the blood-soaked battlefields in America, the marble halls of government, and the grungy offices of diplomatic legations abroad, building suspense as the fortunes of war and international politics changed by the day.

Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, William H. Seward, thought secession was all bluff. Even after shots had been fired, he entertained a scheme to foment a war against Spain, France, or Britain that, in his imagination, might bring the South into patriotic solidarity against an alien enemy. “If any European Power provokes a war,” he told William Howard Russell, war correspondent for the hugely influential Times of London, “we shall not shrink from it. A contest between Great Britain and the United States would wrap the world in fire.” Some thought Seward was coming unhinged from the strain of the secession crisis, but he deliberately and repeatedly issued the same warning to members of the Washington diplomatic corps.

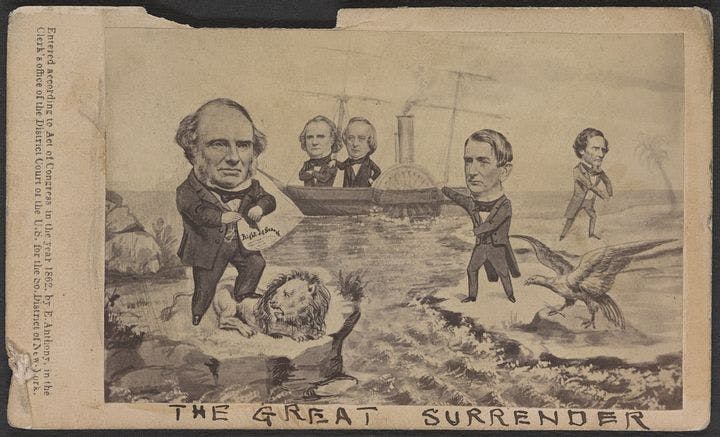

Foreman’s book, despite its ominous title, is about how the highly combustible relations between these “uneasy cousins” came close to igniting but did not. In November 1861, two Confederate agents were apprehended by crewmen of a U.S. warship who had come aboard a British mail packet, the Trent, in the Bahama Channel. The resulting dispute brought the two nations dangerously close to war before Seward agreed to let the agents go.

That Anglo-American relations survived had much to do with Britain’s self-interest—it valued wheat from the North as much as cotton from the South. British leaders also feared a third costly war with the United States, this time with Britain’s tenuous possession of Canada at risk. Most important, by early 1863 Lincoln had transformed the conflict into a war for emancipation, and the British public rallied to the cause of the “Union and Liberty,” forcing Britain not only to remain neutral but to halt the secret construction of Confederate ships in British ports. The Union’s victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July 1863 coincided with the changing perception abroad that the Confederacy’s cause was to perpetuate human slavery and the Union’s was to end it.

Foreman fills her pages with a large cast of fascinating characters, many of them prominent public figures and many more of whom most readers will never have heard: Benjamin Moran, a disgruntled underling in the U.S. legation in London, poured out his tortured soul in a richly detailed diary. Frank Vizetelly, an artist covering the war for The Illustrated London News, seems always to have been on the scene with his keen eye and facile pen. Confederate soldier Francis Dawson, one of some 50,000 Britons who participated in the war on both sides, provided keen observations at every stage of the conflict.

Foreman, who made a splash several years ago with Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, which was made into a movie starring Keira Knightly, has produced a book that is solidly grounded in a prodigious amount of research. Eminent historians have gone before her, but she breaks new ground in telling this vastly complicated story through the eyes of myriad characters. She is also remarkably evenhanded. She brings partisans of North and South, American and British, on stage to tell their story, but in the end she upholds the British tradition of neutrality.

* * *

Don H. Doyle, a professor of history at the University of South Carolina, was a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center earlier this year. He is at work on a book about the international context of the Civil War.

Reviewed: A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War by Amanda Foreman, Random House, 956 pp, 202

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress