Summer 2011

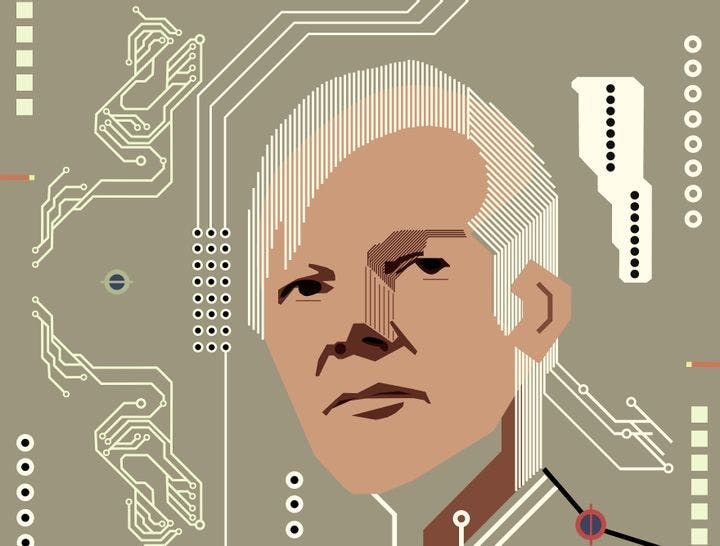

The WikiLeaks Illusion

– Alasdair Roberts

WikiLeaks’ tsunami of revelations from U.S. government sources last year did not change the world, but it did change WikiLeaks.

Late last November, the antisecrecy group WikiLeaks achieved the greatest triumph in its short history. A consortium of major news media organizations — including The New York Times, The Guardian, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, and El País — began publishing excerpts from a quarter-million cables between the U.S. State Department and its diplomatic outposts that WikiLeaks had obtained. The group claimed that the cables constituted “the largest set of confidential documents ever to be released into the public domain.” The Guardian predicted that the disclosures would trigger a “global diplomatic crisis.”

This was the fourth major disclosure orchestrated by WikiLeaks last year. In April, it had released a classified video showing an attack in 2007 by U.S. Army helicopters in the streets of Baghdad that killed 12 people, including two employees of the Reuters news agency. In July, it had collaborated with the news media consortium on the release of 90,000 documents describing U.S. military operations in Afghanistan from 2004 through 2009. These records included new reports of civilian casualties and “friendly fire” incidents. In October came a similar but larger set of documents — almost 400,000 — detailing U.S. military operations in Iraq.

WikiLeaks’ boosters said that the group was waging a war on secrecy, and by the end of 2010 it seemed to be winning. The leaks marked “the end of secrecy in the old-fashioned, Cold War–era sense,” claimed Guardian journalists David Leigh and Luke Harding. A Norwegian politician nominated WikiLeaks for the Nobel Peace Prize, saying that it had helped “redraw the map of information freedom.” “Like him or not,” wrote a TIME magazine journalist in December, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange had “the power to impose his judgment of what should or shouldn’t be secret.”

Did the leaks of 2010 really mark the end of “old-fashioned secrecy?” Not by a long shot. Certainly, new information technologies have made it easier to leak sensitive information and broadcast it to the world. A generation ago, leaking was limited by the need to physically copy and smuggle actual documents. Now it is a matter of dragging, dropping, and clicking Send. But there are still impressive barriers to the kind of “radical transparency” WikiLeaks says it wants to achieve. Indeed, the WikiLeaks experience shows how durable those barriers are.

Let’s begin by putting the leaks in proper perspective. A common way of showing their significance is to emphasize the sheer volume of material. In July 2010, TheGuardian described the release of the Afghan war documents as “one of the biggest leaks in U.S. military history.” Assange, an Australian computer programmer and activist who had founded WikiLeaks in 2006 (and is currently in Britain facing extradition to Sweden on rape and sexual molestation charges), compared it to perhaps the most famous leak in history. “The Pentagon Papers was about 10,000 pages,” he told the United Kingdom’s Channel 4 News, alluding to the secret Pentagon history of America’s involvement in Vietnam that was leaked in 1971. By contrast, there were “about 200,000 pages in this material.”

The Afghan war logs did not hold the record for long. In October, they were supplanted by the Iraq disclosures, “the greatest data leak in the history of the United States military,” according to Der Spiegel. Within weeks, WikiLeaks was warning that this record too would soon be shattered. It boasted on Twitter that its next release, the State Department cables, would be “7x the size of the Iraq War Logs.” Indeed, it was “an astonishing mountain of words,” said the two Guardian journalists. “If the tiny memory stick containing the cables had been a set of printed texts, it would have made up a library containing more than 2,000 sizable books.”

Gauging the significance of leaks based on document volume involves a logical fallacy. The reasoning is this: If we are in possession of a larger number of sensitive documents than ever before, we must also be in possession of a larger proportion of the total stockpile than ever before. But this assumes that the total itself has not changed over time.

In fact, the amount of sensitive information held within the national security apparatus is immensely larger than it was a generation ago. Technological change has caused an explosion in the rate of information production within government agencies, as everywhere else. For example, the leaked State Department cables might have added up to about two gigabytes of data—one-quarter of an eight-gigabyte memory card. By comparison, it has been estimated that the outgoing Bush White House transferred 77 terabytes of data to the National Archives in 2009. That is almost 10,000 memory cards for the White House alone. The holdings of other agencies are even larger.

The truth is that a count of leaked messages tells us nothing about the significance of a breach. Only six percent of the State Department cables that were leaked last year were classified as secret. And the State Department has said that the network from which the cables were extracted was not even the primary vehicle for disseminating its information. In the period in which most of the quarter-million WikiLeaks cables were distributed within the U.S. government, a State Department official said, “we disseminated 2.4 million cables, 10 times as many, through other systems.”

The 2010 disclosures also revealed fundamental problems with the WikiLeaks project. The logic that initially motivated Assange and his colleagues was straightforward: WikiLeaks would post leaked information on the Internet and rely on the public to interpret it, become outraged, and demand reform. The antisecrecy group, which at the start of last year had a core of about 40 volunteers, had great faith in the capacity of the public to do the right thing. Daniel Domscheit-Berg, who was WikiLeaks’ spokesman until he broke with Assange last fall, explained the reasoning in Inside WikiLeaks, a book published earlier this year: “If you provide people sufficient background information, they are capable of behaving correctly and making the right decisions.”

This proposition was soon tested and found wanting. When WikiLeaks released a series of U.S. military counterinsurgency manuals in 2008, Domscheit-Berg thought there would be “outrage around the world, and I expected journalists to beat down our doors.” The manuals described techniques for preventing the overthrow of governments friendly to the United States. In fact, the reaction was negligible. “No one cared,” writes Domscheit-Berg, “because the subject matter was too complex.”

As the British journalist John Lanchester recently observed, WikiLeaks’ “release of information is unprecedented: But it is not journalism. The data need to be interpreted, studied, made into a story.” WikiLeaks attempted to do this itself when it released the Baghdad helicopter video. Assange unveiled the video at a news conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., and packaged it so that its significance would be clear. He titled it Collateral Murder. The edited video, WikiLeaks said, provided evidence of “indiscriminate” and “unprovoked” killing of civilians.

Even with this priming, the public reaction was muted. Many people turned on WikiLeaks itself, charging that it had manipulated the video to bolster its allegations of military misconduct. “This strategy for stirring up public interest was a mistake,” Domscheit-Berg agrees. “A lot of people [felt] ... that they were being led around by the nose.”

The release of the Afghan war documents in July 2010 gave WikiLeaks further evidence of its own limitations. The trove of documents was “vast, confusing, and impossible to navigate,” according to The Guardian’s Leigh and Harding, “an impenetrable forest of military jargon.” Furthermore, the logs contained the names of many individuals who had cooperated with the American military and whose lives could be threatened by disclosure. WikiLeaks recognized the need for a “harm minimization” plan but lacked the field knowledge necessary to make good decisions about what should be withheld.

By last summer, all of these difficulties had driven WikiLeaks to seek its partnership with news media organizations. The consortium that handled the disclosures last fall provided several essential services for the group. It gave technical assistance in organizing data and provided the expertise needed to decode and interpret records. It opened a channel to government officials for conversation about the implications of disclosing information that WikiLeaks itself was unable to establish. Finally, of course, the news media organizations had the capacity to command public attention. They were trusted by readers and possessed a skill in packaging information that WikiLeaks lacked.

By the end of 2010, it was clear that WikiLeaks’ modus operandi had fundamentally changed. It had begun with an unambiguous conception of its role as a receiver and distributor of leaked information. At year’s end, it was performing a different function: It still hoped to serve as a trusted receiver of leaks, but it was now working with mainstream news media to decide how—or if—leaked information ought to be published. For WikiLeaks, this involved difficult concessions. “We were no longer in control of the process,” Domscheit-Berg later wrote. The outflow of leaked information was now constrained by the newspapers’ willingness to invest money and time in sifting through more documents.

For the newspapers that participated in the consortium, the rationale for publishing leaked information was simple. As The New York Times explained in an editorial note when the State Department cables were released in November, Americans “have a right to know what is being done in their name.” The cables “tell the unvarnished story of how the government makes its biggest decisions.” This is the conventional journalistic argument in defense of disclosure, and there is no doubt that the WikiLeaks revelations provided vivid and sometimes disturbing illustrations of the ways in which power is wielded by the United States and its allies.

WikiLeaks itself wanted bigger things to flow from its work. It continued to expect outrage and political action. Assange told Britain’s Channel 4 News last July that he anticipated that the release of the Afghan war documents would shift public opinion against the war. There was a similar expectation following release of the Iraq war documents. But these hopes were again disappointed. In some polls, perceptions about the conduct of the Afghan war actually became more favorable after the WikiLeaks release. Meanwhile, opinion about American engagement in Iraq remained essentially unchanged, as it had been for several years.

There are good reasons why disclosures do not necessarily produce significant changes in policy or politics. Much depends on the context of events. When the Pentagon Papers came out in 1971, they contributed to policy change because a host of other forces were pushing in the same direction. The American public was exhausted by the Vietnam War, which at its peak involved the deployment of almost four times as many troops as are now in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many Americans were also increasingly skeptical of all forms of established authority. The federal government’s status was further tarnished by other revelations about abuses of power by the White House, CIA, and FBI.

We live in very different times. There is no popular movement against U.S. military engagement overseas, no broad reaction against established authority in American society, no youth rebellion. The public mood in the United States is one of economic uncertainty and physical insecurity. Many Americans want an assurance that their government is willing and able to act forcefully in the pursuit of U.S. interests. In this climate, the incidents revealed by WikiLeaks — spying on United Nations diplomats, covert military action against terrorists, negotiations with regimes that are corrupt or guilty of human rights abuses—might not even be construed as abuses of power at all. On the contrary, they could be regarded as proof that the U.S. government is prepared to get its hands dirty to protect its citizens.

Indeed, it could be said that WikiLeaks was doing the one thing Americans least wished for: increasing instability and their sense of anxiety. The more WikiLeaks disclosed last year, the more American public opinion hardened against it. By December, according to a CNN poll, almost 80 percent of Americans disapproved of WikiLeaks’ release of U.S. diplomatic and military documents. In a CBS News poll, most respondents said they thought the disclosures were likely to hurt U.S. foreign relations. Three-quarters affirmed that there are “some things the public does not have a right to know if it might affect national security.”

As WikiLeaks waited fruitlessly for public outrage, it began to see another obstacle to the execution of its program. WikiLeaks relies on the Internet for the rapid dissemination of leaked information. The assumption, which seemed plausible in the early days of cyberspace, is that the Internet is a vast global commons — a free space that imposes no barrier on the flow of data. But even online, commercial and political considerations routinely compromise the movement of information.

This reality was quickly illustrated after the release of the State Department cables on November 28. Three days later, Amazon Web Services, a subsidiary of Amazon.com that rents space for the storage of digitized information, stopped acting as a host for WikiLeaks’ material, alleging that the group had violated its terms of service. The same day, a smaller firm that provides online graphics capabilities, Tableau Software, discontinued its support. The firm that managed WikiLeaks’ domain name, EveryDNS.net, also suspended services, so that the domain name wikileaks.org was no longer operable. On December 20, Apple removed an application from its online store that offered iPhone and iPad users access to the State Department cables.

All of these actions complicated WikiLeaks’ ability to distribute leaked information. Decisions by other organizations also undermined its financial viability. Five days after the State Department disclosures, PayPal, which manages online payments, announced that it would no longer process donations to WikiLeaks, alleging that the group had violated its terms of service by encouraging or facilitating illegal activity. MasterCard and Visa Europe soon followed suit.

Critics alleged that these firms were acting in response to political pressure, and many American legislators did in fact call on businesses to break with WikiLeaks. But direct political pressure was hardly necessary; cold commercial judgment led to the same decision. WikiLeaks produced little revenue for any of these businesses but threatened to entangle all of them in public controversy. A public-relations specialist told Seattle’s KIRO News that it was “bizarre” for Amazon to assist WikiLeaks during a holiday season: “I don’t think you mix politics with retail.” Worse still, businesses were exposed to cyberattacks by opponents of WikiLeaks within the hacker community that disrupted their relationships with other, more profitable clients.

These business decisions hurt WikiLeaks significantly. Assange said they amounted to “economic censorship” and claimed that actions by these financial intermediaries were costing WikiLeaks $650,000 per week in lost donations.

The leaks also provoked a vigorous reaction by the U.S. government. The Army came down hard on Private Bradley Manning, the apparent source of all four of the 2010 disclosures, bringing 34 charges against him. The most serious of these, aiding the enemy, could result in a death sentence, although prosecutors have said they will not seek one. The government is also investigating other individuals in connection with the leaks. Some in Congress have used the episodes to argue for strengthening the law on unauthorized disclosure of national security information, and federal agencies have tightened administrative controls on access to sensitive information. These steps, which may well produce a result precisely the opposite of what WikiLeaks intends by reducing citizens’ access to information about the government, have been taken by an administration that promised on its first day in office to “usher in a new era of open government.”

WikiLeaks is predicated on the assumption that the social order—the set of structures that channel and legitimize power — is both deceptive and brittle: deceptive in the sense that most people who observe the social order are unaware of the ways in which power is actually used, and brittle in the sense that it is at risk of collapse once people are shown the true nature of things. The primary goal, therefore, is revelation of the truth. In the past it was difficult to do this, mainly because primitive technologies made it difficult to collect and disseminate damning information. But now these technological barriers are gone. And once information is set free, the theory goes, the world will change.

We have seen some of the difficulties with this viewpoint. Even in the age of the Internet, there is no such thing as the instantaneous and complete revelation of the truth. In its undigested form, information often has no transformative power at all. Raw data must be distilled and interpreted, and the attention of a distracted audience must be captured. The process by which this is done is complex and easily influenced by commercial and governmental interests. This was true before the advent of the Internet and remains true today.

Beyond this, there is a final and larger problem. It may well be that many of the things WikiLeaks imagines are secrets are not really secrets at all. It may be that what WikiLeaks revealed when it drew back the curtain is more or less what most Americans already suspected had been going on, and were therefore prepared to tolerate.

To put it another way, much of what WikiLeaks has released might best be described as open secrets. It would have been no great shock to most Americans, for example, to learn about the United States’ covert activities against terrorists in Yemen. “The only surprising thing about the WikiLeaks revelations is that they contain no surprises,” says the noted Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek, a professor at the European Graduate School. “The real disturbance was at the level of appearances: We can no longer pretend we don’t know what everyone knows we know.”

In a sense, it was odd to expect that there would be great surprises. The diplomatic and national security establishment of the U.S. government employs millions of people. Most of the critical decisions about the development of foreign policy, and about the apparatus necessary to execute that policy, have been made openly by democratically elected leaders, and sanctioned by voters in national elections over the course of 60 years. In broad terms, Americans know how U.S. power is exercised, and for what purpose. And so there are limits to what WikiLeaks can unveil. Even New York Times executive editor Bill Keller conceded that the disclosures did not “expose some deep, unsuspected perfidy in high places.” They provide only “texture, nuance, and drama.”

None of this is an argument for complacency about government secrecy. Precisely because of the scale and importance of the national security apparatus, it ought to be subjected to close scrutiny. Existing oversight mechanisms such as freedom of information laws and declassification policies are inadequate and should be strengthened. The monitoring capacity of news media outlets and other nongovernmental organizations must be enhanced. And citizens should be encouraged to engage more deeply in debates about the aims and methods of U.S. foreign policy. All of these steps involve hard work. There is no technological quick fix. A major difficulty with the WikiLeaks project is that it may delude us into believing otherwise.

—

Alasdair Roberts, a former Woodrow Wilson Center fellow, is Rappaport Professor of Law and Public Policy at Suffolk University Law School. His books include Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age (2006) and The Logic of Discipline: Global Capitalism and the Architecture of Government (2010).

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Up next in this issue