Summer 2012

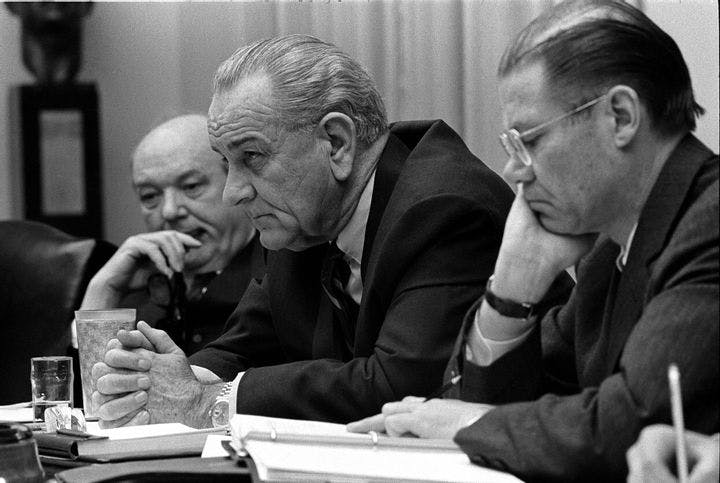

Proud American: Lyndon Johnson and "The Passage of Power"

– Aaron Mesh

The "Johnson treatment" meets the "Kennedy mystique" in Robert Caro's latest installment on Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Aides to Lyndon Baines Johnson always knew when their boss had decided to engage in a political battle. Once he had finished precisely calibrating the personal costs and benefits, he would begin to gather momentum in a ritual that allies described as “revving up”: the effort to persuade himself of the goodness of his cause, regardless of whether he had previously supported or opposed it. Thus motivated, he would “get all worked up,” as his longtime lawyer, Ed Clark, put it, “all worked up and emotional, and work all day and night, and sacrifice, and say, ‘Follow me for the cause!’—‘Let’s do this because it’s right!’ ”

Those who have read Robert A. Caro’s three previous biographical volumes on Johnson will recognize this groundswell—the sudden marshaling of outsized energies—because it is also the pattern of these mammoth, magnificent books. They chronicle in exhaustive detail the strengths and flaws of the 36th president of the United States, then surge forward toward a pivotal moment with the full weight of that character study behind them.

In this fourth installment—a comparatively trim 712 pages—the payoff is even greater. In the course of this book, Johnson is bumped from presumptive 1960 Democratic presidential nominee to the bottom half of John F. Kennedy’s ticket, then suffers the further abasement of being vice president in an administration that despises and pities him. His political future shrinks to a narrowness that Caro, with typical flair, compares to “the Dallas canyon” of office buildings and warehouses the presidential motorcade drove through on November 22, 1963. The assassin’s bullet that kills Kennedy instantly makes Johnson president, and the second half of The Passage of Power is a headlong rush as LBJ realizes what he can do when handed great authority.

Much of the book’s first half can be summed up with another Johnson phrase, familiar from previous books: “Too slow. Too slow.” Caro has corralled his usual army of details: some uncovered serendipitously (he reveals in the footnotes that his back doctor also treated JFK) but mostly during extensive interviews. To these he adds a deliciously maddening tendency to reach the cusp of a conflict, then pan to a wider angle to give a comprehensive view of its context.

Johnson finally meets his match in the Kennedys—especially Robert, with whom he develops “one of the great blood feuds in American political history.” In the corridors of a Los Angeles hotel during the 1960 nominating convention, JFK offers Johnson the vice presidency, a position that Bobby tries to persuade him not to accept. Soon Johnson finds himself a hick pariah among the denizens of the Camelot inner circle, who nickname him “Rufus Cornpone.” There are several episodes of wounding humiliation (as when Johnson tries to dance with JFK mistress Helen Chavchavadze at a party, slips and falls, and finds himself lying on her, according to one of the guests, “like a lox”).

But these doldrums are a necessary backdrop to accentuate the whirlwind of activity Johnson undertakes once he enters the Oval Office. Before, actually: It’s in the first three days after Kennedy’s assassination, when Johnson is still holed up in room 274 of the Executive Office Building, across the street from the White House, that he makes the choices that will not only preserve the country from chaos but elevate its character. Told that he shouldn’t risk his political chips on the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he replies, “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for?”

Nothing is so moving as when a hard man decides to do good. By the time this Texas politician takes presidential office, Caro has shown us exactly what kind of man he is—grasping, bullying, and almost bottomlessly corrupt—and so it is all the more affecting to see him recognize, if only briefly, a higher purpose to his ambition: giving basic freedoms to black Americans denied them by segregation, and basic human dignity to poor people denied them by inequality of opportunity. The Passage of Power is about how Lyndon Johnson gained power, but it is also about how he conducted it to others.

The book reaches its own emotional peak in an impromptu “revving up” speech delivered to the nation’s governors gathered for Kennedy’s funeral. Johnson knows he’ll need their leverage to pass civil rights legislation, and he leans on them with this pledge: “I am not the best man in the world at this job, and I was thrown into it through circumstances, but I am in it and I am not going to run from it. I am going to be at it from daylight to midnight, and with your help and God’s help we are going to make not ourselves proud that we are Americans but we are going to make the rest of the world proud that there is an American in it.” At this moment, the reader experiences a fleeting but genuinely stirring sensation: pride that Lyndon Johnson was an American.

Aaron Mesh is a reporter for Willamette Week, an alternative weekly newspaper in Portland, Oregon. Reviewed: The Passage of Power by Robert A. Caro, Knopf, 712 pp.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons