Summer 2012

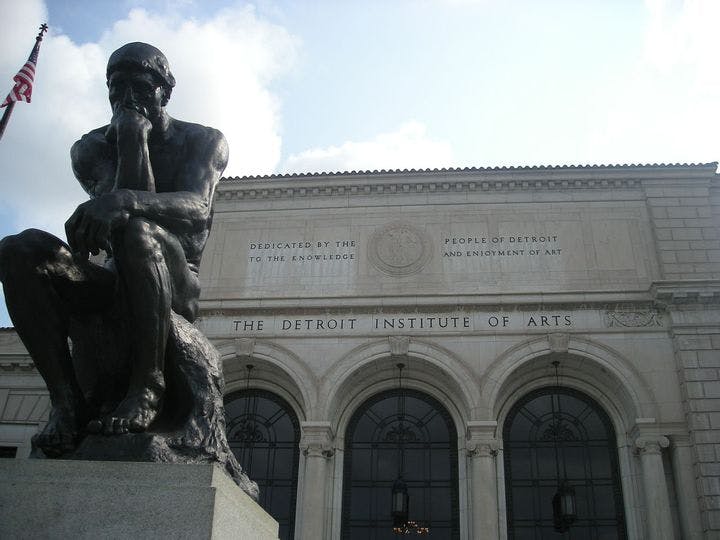

Is the U.S. the "most Philosophical Nation on Earth"?

– Troy Jollimore

America is "an unprecedented marketplace of truth and argument that far surpasses ancient Greece, Cartesian France, 19th-century Germany, or any other place one can name over the past three millennia."

Carlin Romano begins his new book with a provocative thesis: The United States is the most philosophical nation on earth. Romano, a critic at large for The Chronicle of Higher Education and professor of philosophy and humanities at Ursinus College, declares his stance in the first few pages of America the Philosophical: “The surprising little secret of our ardently capitalist, famously materialist, heavily iPodded, iPadded, and iPhoned society is that America in the early 21st century towers as the most philosophical culture in the history of the world, an unprecedented marketplace of truth and argument that far surpasses ancient Greece, Cartesian France, 19th-century Germany, or any other place one can name over the past three millennia.”

How could such a hotbed of philosophy have gained the reputation for being an un-philosophical, indeed downright anti-intellectual culture? Romano’s explanation is that the word “philosophy” has come to be identified, incorrectly, with the work of a small number of Ivy League philosophy professors in the analytic tradition whose research concerns technical matters related to epistemology (i.e., the theory of knowledge)—people such as Willard Van Orman Quine, Donald Davidson, and Wilfrid Sellars, who saw science as the model for good philosophy and regarded logic as their primary instrument.

Outside of this sphere stands another American philosophical tradition, which is less concerned with the fine points of logic than with rhetoric and imagination, would rather persuade than prove, and cares less about precision and accuracy than utility. This tradition, which Romano refers to with his label “America the Philosophical,” is largely derived from such founding pragmatist philosophers as Charles Sanders Peirce and William James. In Romano’s view, it also includes a wildly varied range of thinkers and figures, among them Richard Posner, Cornel West, Susan Sontag, Oliver Sacks, Robert Coles, Robert Fulghum, and even Hugh Hefner—as well as Richard Rorty, whom Romano credits as the man who revealed analytic epistemology to be a sham.

One could, of course, accept the existence of these two traditions without accusing either of being spurious. But Romano misses no opportunity to heap scorn on the practitioners of analytic epistemology. Unfortunately, the overheated rhetoric he habitually employs makes him seem at least as intolerant as the allegedly narrow-minded academics he is attacking. At one point, he charges that “post-Rortyan epistemologists” are “oblivious in their inbred conventions to time and intellectual culture passing them by, [and] continue to focus on narrow syllogistic arguments in the theory of knowledge.” The reasoning of mainstream analytic epistemologists takes a wide variety of forms, and categorizing them as makers of “narrow syllogistic arguments” is a caricature at best. After a while, it appears that “analytic epistemology” functions as a label for whatever Romano doesn’t like, philosophically speaking.

Other than the fact that he finds them interesting, the figures Romano discusses with approval seem to have little in common. He gives no sense of what particular issues or debates he takes to define or even matter to philosophy. Perhaps this makes a kind of sense, given Romano’s apparent understanding of pragmatism as holding that it’s the practical effects of an idea on society and history, rather than its content, that matter.

This understanding explains how Romano can assert that the United States today is “the most philosophical culture in the history of the world.” What is important to him is “the quantity of [America’s] arguments, the diversity of its viewpoints, [and] the cockiness with which its citizens express their opinions.” Skeptics will remind us that what matters, philosophically, is not just the quantity of debate but its quality, the degree of thoughtfulness it expresses.

Romano also tenders as evidence of America’s philosophical bent “the intensity of its hunt for evidence and information, the widespread rejection of truths imposed by authority or tradition alone, [and] the resistance to false claims or justification and legitimacy.” But are Americans really more committed than other people to evidence-based belief, or more rational in their skepticism? American attitudes toward evolution and global warming, not to mention the willingness of large numbers of Americans to accept the epistemic authority of their favored news outlet, casts doubt on Romano’s claim. And Romano has very little to say about the role of religious commitments in Americans’ thinking.

Is this to say that the United States is an entirely un-philosophical society? Not at all. But America the Philosophical violates the first rule of good philosophy: It insists on treating this complex question as if it were a simple one.

Troy Jollimore is a professor of philosophy at California State University, Chico. He is the author of Love’s Vision (2011) and the forthcoming book On Loyalty, as well as two volumes of poetry.

Reviewed: America the Philosophical by Carlin Romano, Knopf, 672 pp.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons