Fall 2014

Denmark's Civil Unions: One Giant Leap for Mankind

– Daniel Krieger

When Denmark became the first country to legalize civil unions for gay couples, it marked the start of a new era of LGBTI rights, with global ripples that continue to reverberate today.

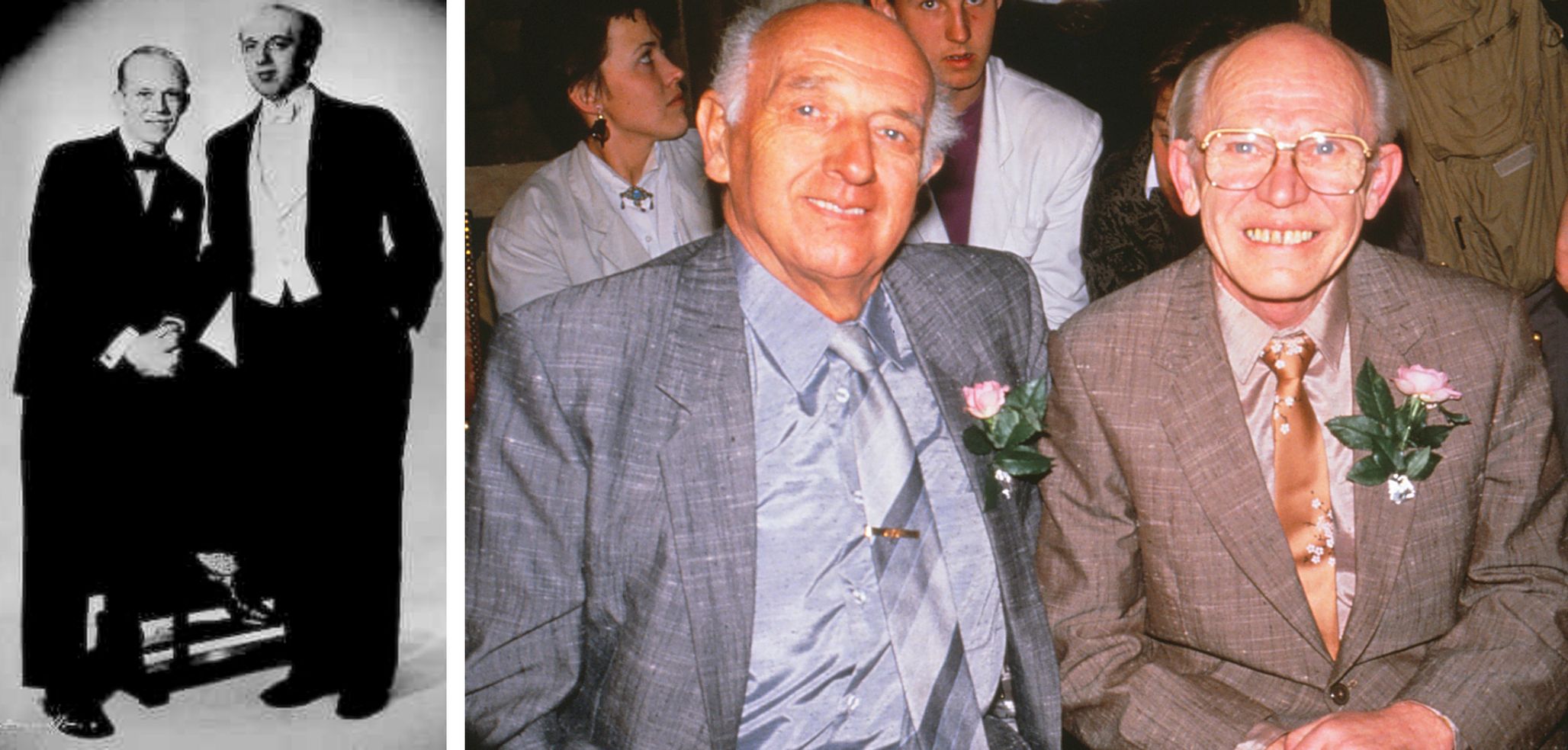

ON OCTOBER 1, 1989, AN EVENT UNLIKE ANY BEFORE in history took place at the Copenhagen town hall in Denmark. That Sunday, a national law went into effect that allowed same-sex couples to be joined in a civil union, and 11 gay male couples did just that — a school psychologist, a Lutheran minister, and a high school teacher among them. One of the grooms, Eigil Axgil (né Eskildsen), then 67 years old, told Rex Wockner, an American journalist who was there covering it, “We just never could have dreamed that we would get this far.”

They had plenty of reason for doubt. Four decades earlier, Eigil’s partner, Axel Axgil (né Lundahl-Madsen), launched Denmark’s first gay rights organization, the League of 1948 (whose name was later changed to the less-discreet Danish National Organization for Gays and Lesbians, or LBL for short.) Out of the closet, Axel was fired from his bookkeeping job and evicted by his landlord, but forged ahead. It was his group’s tireless lobbying over the years that eventually laid the groundwork that led to that historic day in 1989.

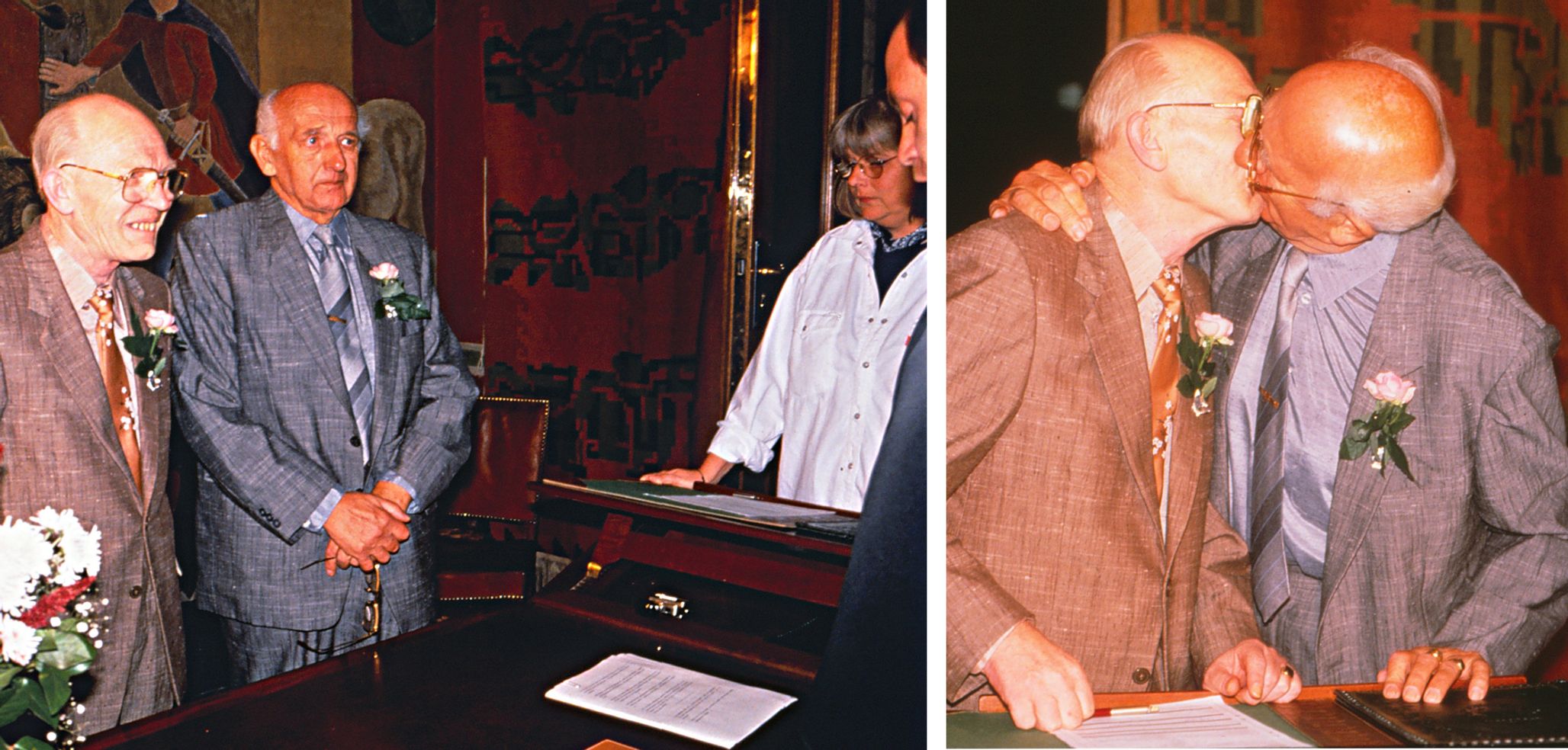

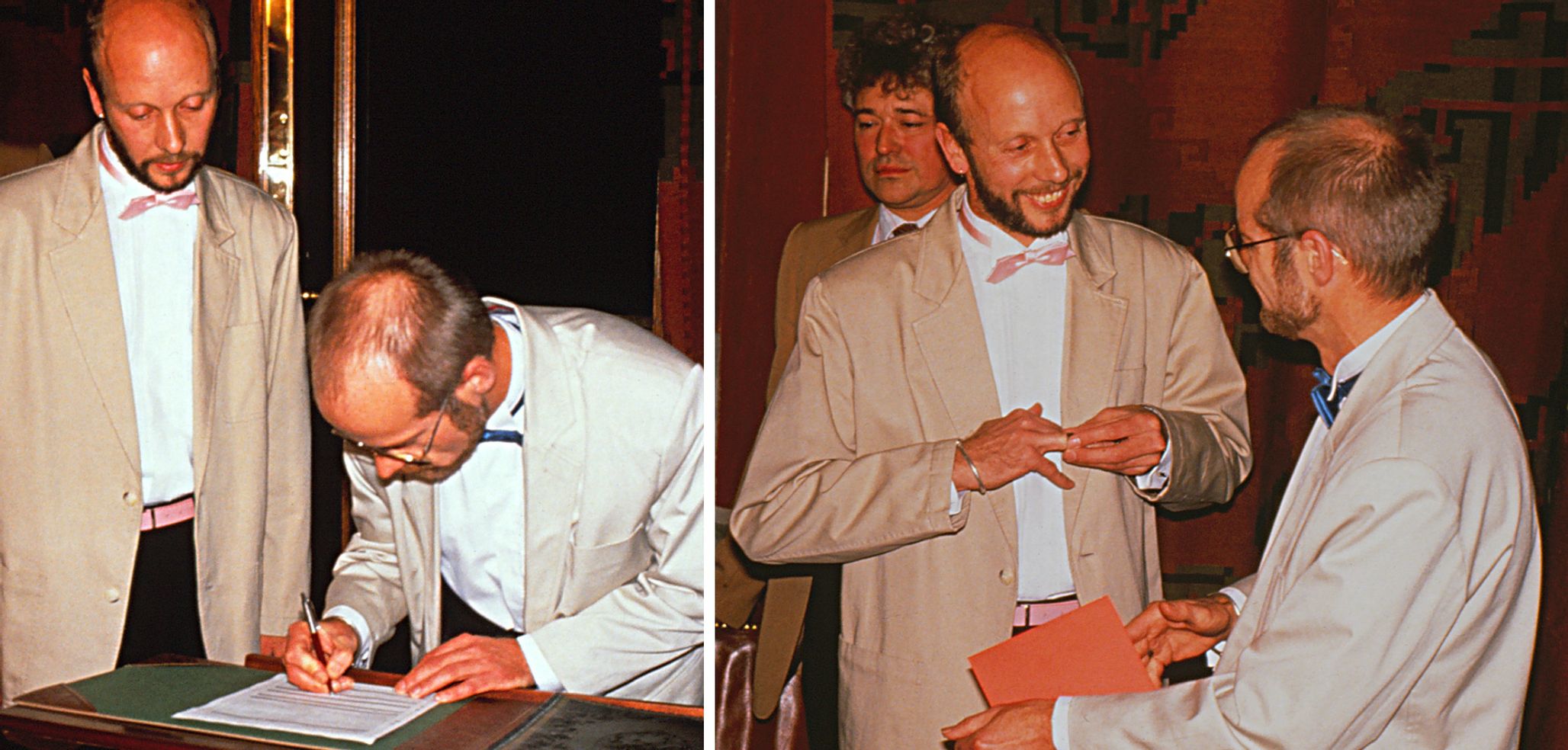

Wockner, who syndicated his breaking news stories to the gay press for more than two decades before retiring a few years ago, remembers Copenhagen Vice Mayor Tom Ahlberg speaking to the group for a few minutes before the ceremonies, reminding the 22 grooms that the rite of passage they were about to undergo would call for “love, helpfulness, and tolerance.” Then, starting with the Axgils (Axel and Eigel took the surname years earlier, a portmanteau of their first names), each couple went into a small adjacent room where Ahlberg asked: “Will you take [name] as your partner?” The only linguistic tweak in the ceremony was the label: the union was called a “registered partnership” rather than a “marriage.” After exchanging vows, Eigel and Axel each signed a certificate, and the next 10 couples followed, one by one. The grooms walked down the town hall steps amid a shower of rice and confetti as bottles of champagne popped and toasts were made.

Three of the more politically active couples were whisked away from the mob of photographers and well-wishers in horse-drawn carriages and taken to the LBL office nearby for a celebration and press conference. When Eigil Axgil was asked if he had any encouraging words for gay couples around the world, he said: “Be open, come out, keep fighting. This is the only way to move anything. If everyone comes out of the closet, then this will happen everywhere.”

Though Denmark's Registered Partnership Law, the first of its kind on earth, gave gay and lesbian couples most of the same rights as married heterosexuals (not to mention some of the less-enjoyable features of the institution, like paying alimony), it fell short on securing adoption rights or church marriage ceremonies. Nevertheless, it was a giant step in the fight for equality.

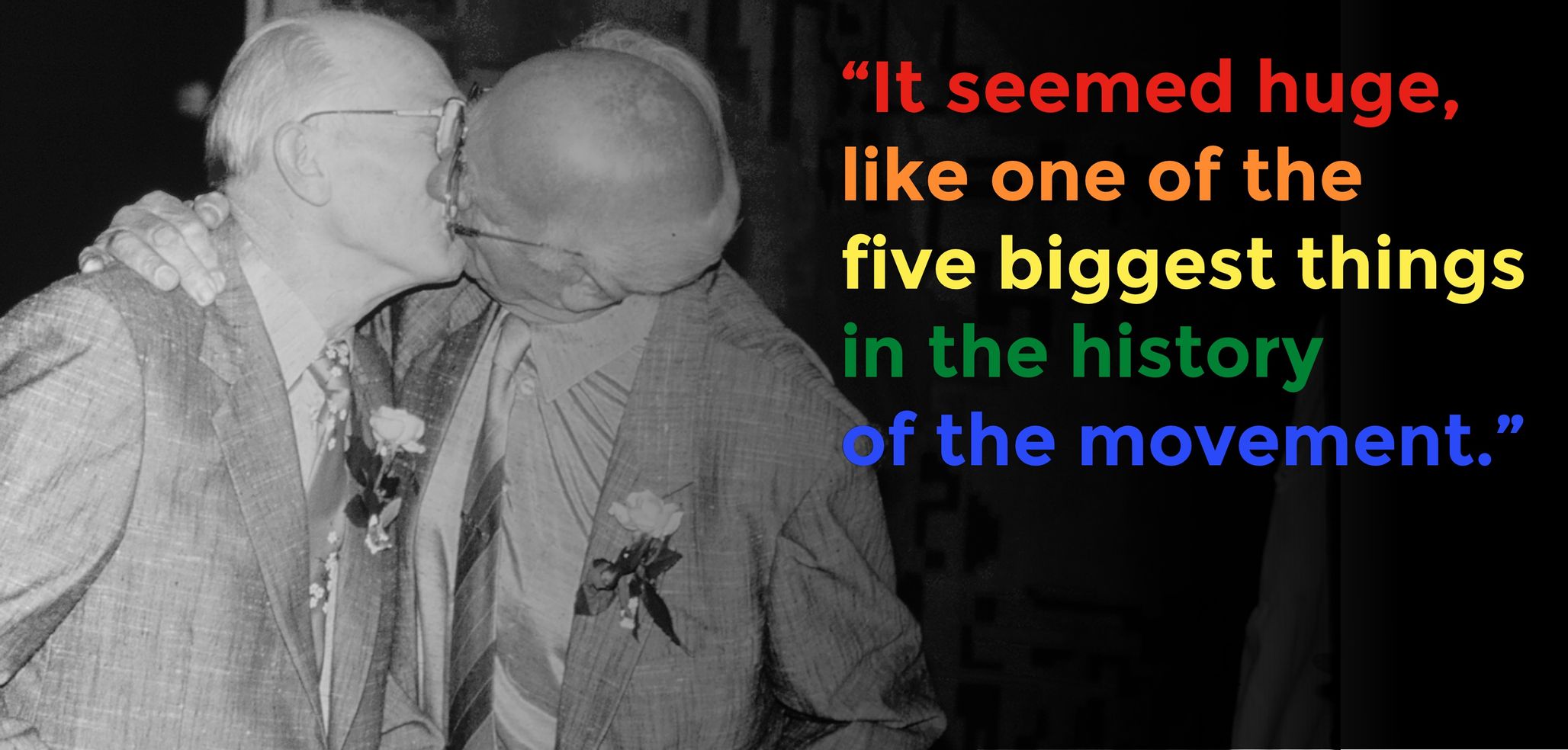

“It seemed huge, like one of the five biggest things in the history of the movement,” says Wockner, putting it right up there with the violent protests at the Stonewall Inn in 1969, which helped spark the gay rights movement in the U.S., and the 1987 March on Washington, which drew 200,000 participants. Several local daily newspapers — one of which called it “the event of the year” — wrote about the day in glowingly positive terms, printing a spread of color photos of the grooms kissing and carrying each other over the threshold. Wockner recalls that he didn’t notice any protesters outside city hall; according to polls at the time, three out of four Danes approved the new civil union law.

Wockner, who has spent much time in Denmark over the years, says that today, the country “feels like a place where gay marriage is not any kind of issue at all anymore for almost anybody — gay or straight.”

LOOKING AT HOW MUCH LGBTI RIGHTS HAVE EVOLVED in the past 25 years, with 17 countries now fully recognizing same-sex marriage, the occasion might seem less momentous in hindsight. But Denmark was the first country to get that ball rolling, slow moving though it was at the start.

Juris Lavrikovs, the communications manager at ILGA-Europe, a European LGBTI rights organization, sees Denmark's legal model of same-sex civil unions as a pioneering step. “We regard it as quite revolutionary and significant because it paved the way for recognition in the rights of same-sex couples around the world,” he said in a phone interview from the ILGA-Europe office in Brussels.

Not long after 1989, other Scandinavian countries followed suit — Norway adopting civil partnerships in 1993, and Sweden in 1995. The movement soon spread beyond Scandinavia, with others in Europe adopting the model, which became a stepping-stone for laws that actually legalized same-sex marriage, going beyond mere “partnerships.” “Marriage” first debuted nationally in 2001 in the Netherlands, followed by Belgium two years later, and Spain and Canada two years after that. South Africa did it in 2006, then Norway, Sweden, Argentina, Iceland, and Portugal. Denmark belatedly joined their ranks, legalizing same-sex marriage in 2012.

When it comes to policies that affect LGBTI people, ILGA-Europe ranks Denmark behind some of its European counterparts. In their “rainbow Europe” report, the organization rates each of the 49 European countries in six “thematic” categories — equality and non discrimination; bias-motivated speech/violence; legal gender recognition; freedom of assembly, association, and expression; and asylum — and more than 45 subcategories pertaining to the treatment of LGBTI citizens. Each country is given an overall score on a scale ranging from zero (“gross violations of human rights”) to 100 (“respect of human rights; full equality”). Today, Denmark has a score of 60 (tenth overall). The worst offender, Russia, scores just six, while the highest-ranked country, the United Kingdom — which once sent Oscar Wilde to prison for “acts of gross indecency with other male persons” — boasts a score 82.

Søren Laursen, the chairperson of LGBT Denmark (formerly LBL), claims that the rainbow map doesn't convey the full picture: because the ranking system only grants points for laws, it fails to take into account the common practices and de facto treatment of LGBTI people. Denmark, for instance, does offer asylum, but it isn’t codified into law. Similarly, Denmark should fare better in next year’s grades, having recently enacted a law that enables transgender people to legally declare their gender identity by themselves.

In a phone interview from LGBT Denmark's Copenhagen office, Laursen recounted the long and winding process that led to the passage of the 1989 Registered Partnership Law, tracing its origin to 1969, when a parliamentary committee was formed to consider revisions to the country’s marriage laws. Impatient with the glacial pace of legislative progress, LBL wrote its own proposal in 1982, coining the term “registered partnerships” in the process. In parliament, the LBL-authored bill faced fierce resistance and struggled to find politicians willing to pledge their support.

Though the group had allies in the center and on the left, “the right-wing government was absolutely opposed to anything,” says Laursen. Despite that, LBL — having already formed working relationships with some legislators by partnering on AIDS prevention efforts — succeeded in bringing the issue up for debate, prompting parliament to create a committee dubbed the “HomoCommission” to examine the challenges faced by LGBTI Danes.

Underfunded and with some members opposed to gay civil unions from the get-go, the commission rejected the idea of registered partnerships, instead favoring amendments to existing marriage benefit laws as a remedy to the inequality. But LBL had already convinced some jurists in parliament to put forth another proposal much simpler than the first. It defined a registered partnership as a marriage, but with caveats, leaving out the ability to adopt children or get married in a church. Because this was pushing the envelope so far, says Laursen, “there was an understanding among our lobby and politicians that it would be impossible to get a majority for same-sex marriage at that time.”

Some members of parliament, however, especially the Christian People's Party, still felt the new proposal was asking too much, and leveled some quite imaginative arguments against it, as detailed in William N. Eskridge and Darren R. Spedale’s 2007 book, Gay Marriage: for Better Or for Worse?: What We've Learned from the Evidence. One claim (still popular today in the United States) was that equality would violate the “sanctity of marriage,” which the Bible says must be between a man and a woman. Others argued that the bill would make Denmark a top destination for the sexual deviants of the world, that it would be harmful to children, that few homosexuals would want such a civil union anyway, and that the bill would harm the country's reputation. To this, one member of parliament countered that it was more likely that “Denmark's first step will rub off on other lands.”

AFTER SITTING IN PARLIAMENT FOR A YEAR AND A HALF, on May 26, 1989, the bill was finally voted on. Deciding by conscience rather than party, the members cast their votes by pressing a red or green button: 71 in favor, 47 against, and five abstentions. From a viewing gallery, visitors stood and cheered and bowed towards the legislators with gratitude. By the year’s end, more than 300 gay couples had registered their partnerships; over the next two decades, 4,000 more couples joined them.

In addition to granting gays and lesbians near-equality, some believe that the law led to a more positive view of the LGBTI community throughout Danish society. “The ‘registered partnership’ made gays and lesbians extremely visible everywhere,” says Laursen, in part because of all the updates to bureaucratic paperwork that the law required. One reason why Denmark was the first to do this, Laursen theorizes, is that its political culture is such that any member of parliament can propose a law and try to get a majority, unlike many other countries where such a proposal would likely languish.

Negative reactions to the bill’s passage came from marginal groups that represent a sliver of the Danish population. “They still exist and are still vocal against us,” says Laursen, “but they have no say in Danish society.” Right-wing dominance of the government in the 2000s, he says, is a major reason why it took Denmark until 2012 to grant marriage rights to same-sex partners (making it the 11th country to do so).

For the first decade of the 21st century, the Danish People’s Party and the Conservatives were in power. They were staunchly against gay marriage, and had the power to block it. But with momentum behind the equality movement and shifting political winds giving parliamentary control to a center-left government, advocates made gains. In 2010, adoption rights were finally extended to same-sex partners. Two years later, marriage equality activists passed a law that opened up marriage to same-sex couples and gave the Church of Denmark (a state religion in the Lutheran tradition) permission to either perform same-sex marriage ceremonies or opt out. A poll taken six months after the bill passed found that 79 percent of Danes supported marriage equality.

TODAY, LAURSEN SAYS THAT THOUGH HE APPRECIATES THE ACHIEVEMENT of registered partnerships, ultimately “we should not have special legislation for certain groups in society. We should have one law for all, and that’s what happened in 2012."

Evan Wolfson, a major force behind the push for same-sex marriage in the United States and the founder and president of Freedom to Marry, echoes the sentiment: “The only way to treat people equally is to treat them equally.” In his view, Denmark's registered partnerships, though groundbreaking, did not accomplish that. “Denmark achieved something that moved us forward more than we had in any other country, and that was good. But at the same time, it didn't fully hit the mark, because it didn't secure full equality. By introducing the separate and unequal standard as arguably being okay in some people’s minds, it actually in some ways also delayed progress.”

On the front lines of the fight for marriage equality over the past several decades, Wolfson was in the camp that wouldn’t endorse civil unions. “It's the same fight,” he says. “My argument has always been that if we’re going to have to fight anyway, why not fight over what we really want?”

For Wolfson and allies, after many years of battle, victory is in sight. Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have recognized marriage equality, starting with Massachusetts in 2004. “We’ve built that critical mass of states and critical mass of support, and now we can say to the U.S. Supreme Court, ‘It's time,’” says Wolfson. If things go the way he hopes, next year the U.S. Supreme Court may issue a ruling that would legalize gay marriage in all 50 states.

But calling it “gay marriage” isn't quite right.

“What we’re winning is not ‘gay marriage,’” says Wolfson. “It’s marriage. It’s just saying gay people can't be excluded from the same marriage that exists for others.”

That bold step taken by Denmark 25 years ago did end up inspiring other countries, many of which have since ventured even further. Others, like the United States, are still working on it.

Here, just as interracial marriage eventually became an accepted norm, one day lawfully wedded same-sex couples across the country might also be just an everyday part of the way things are.

As Wolfson said, it’s time.

* * *

Daniel Krieger is a journalist based in New York City. More of his work can be found at DanielKrieger.net.

Cover photo courtesy of EPA/Keld Navntoft/Denmark Out/Newscom