Fall 2014

Hirohito's Long Shadow

– Shihoko Goto

Hirohito's descendants remain committed to Japan's traditional values, which desperately need reform.

Until the end of World War II, Emperor Hirohito was a living god in the minds of many Japanese. By the time of his death in 1989, he was more of a phoenix: the personification of a Japan that was able to rise from the ashes of war. His 64-year reign, the Showa era, was a story of resilience and triumph that weathered military defeat and ultimately conquered the world as an economic powerhouse.

Only four decades after Tokyo was reduced to rubble, Japan rebuilt itself into the second-largest economy in the world. So ascendent was Japan that many in the West began to fear that Japan might simply buy out some of the hottest (and not so hot) assets from across the globe — Hollywood movie studios, Rockefeller Center, the Pebble Beach golf course, and even Van Gogh’s sunflower paintings. Such international worries, however, soon dissipated as Japan fell into an economic abyss shortly after Hirohito’s reign, from which it is only now showing signs of re-emergence.

Over the past 25 years since the emperor was laid to rest, Japan has grappled with its own narrative of exceptionalism. It’s easy to fall into the trap of nostalgia—longing for the Showa era days gone by when Japan was clearly the biggest power in Asia and its people were confident of economic superiority underpinned by a diligent workforce, unique business practices, and traditional values.

Change has been painfully slow for Japanese women, and nothing short of a social revolution will propel Japan’s economy even close to what it once was. Yet, the descendants of Emperor Hirohito remain committed to preserving a Japanese value system that is in dire need of sweeping social reform.

The descendants of Emperor Hirohito remain committed to preserving a value system in dire need of sweeping reform

Take, for instance, none other than Hirohito’s own granddaughter-in-law, Princess Masako. When the Harvard- and Oxford-educated career diplomat married Crown Prince Naruhito 21 years ago, hopes were high that she would take on an active role in modernizing the often staid imperial household — she could encourage greater diplomatic exchange between royalty worldwide, even if she couldn’t reach the global celebrity status of a Princess Diana or Queen Noor. Instead, as Princess Masako struggled to conceive a child over the years, she made fewer and fewer public appearances, and almost never traveled overseas.

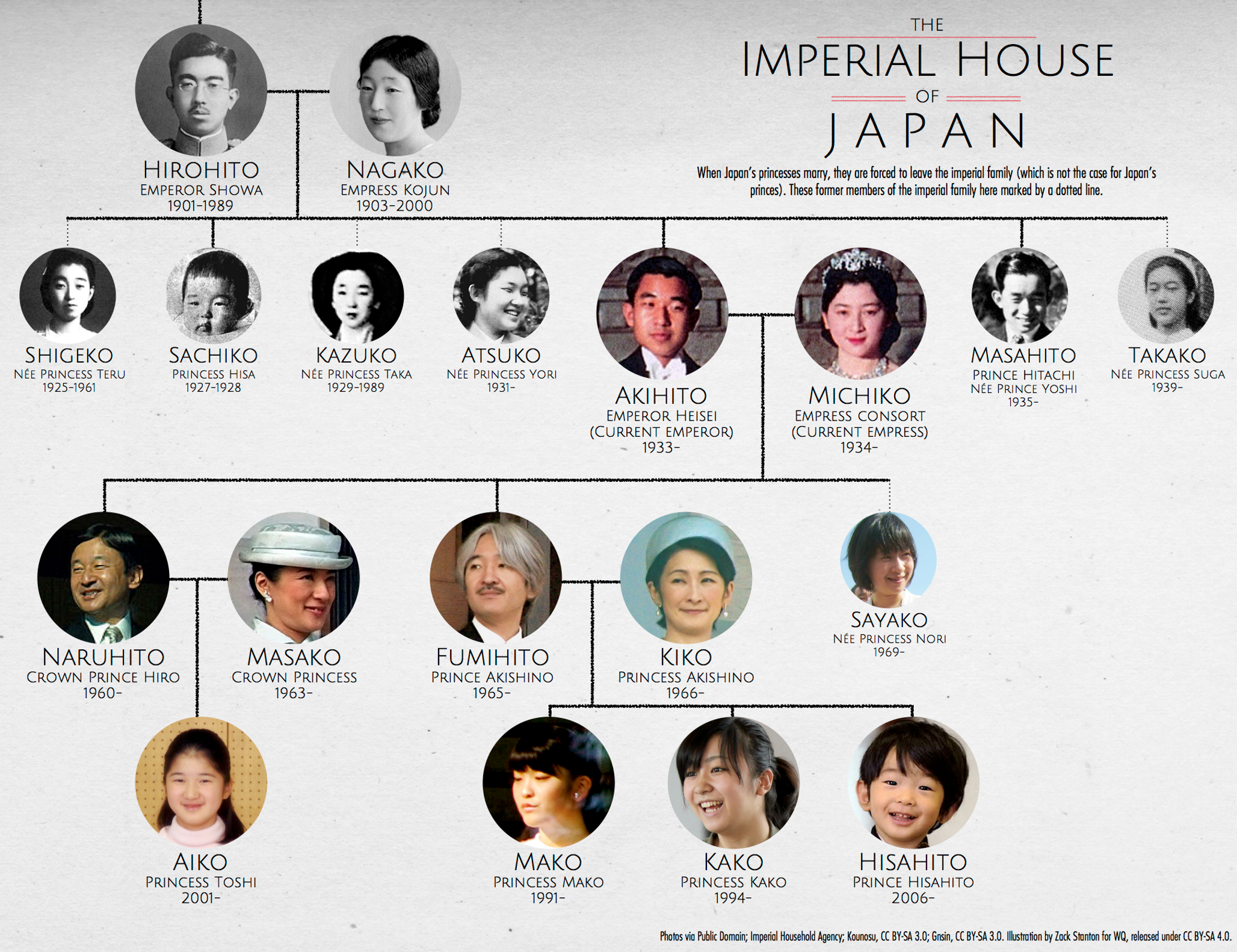

When she did succeed in giving birth to Princess Aiko 12 years ago, national joy was muted: a woman still cannot succeed to the Chrysanthemum Throne. Granted, parliament began debating the possibility of reforming the constitution so that women could inherit the crown, but that conversation was quickly quashed when Princess Kiko, the wife of Naruhito’s younger brother, had a baby boy in 2006. This means that once Crown Prince Naruhito ascends to the throne, his successor will be neither his daughter nor his two female nieces, but his nephew, Hisahito — who will leapfrog over all of them to take the emperorship. Princess Kiko is the mother of the emperor-to-be, and has overtaken Princess Masako in stature.

Although the stakes and public exposure are unrelatable, the troubles are. The imperial household is plagued with the same challenges of modern families everywhere: grappling with infertility, suffering awkward dynamics between relatives, trying to support high-powered women who want to carve out a new path for growth while juggling family and work commitments. Yet instead of championing any of the hurdles they face, the imperial family has essentially tried to bury the fact that they struggle. Far from speaking out on the difficulties of conceiving, or discussing women’s rights, they remain silent and abide solely to follow their official duties of attending politically correct public events.

The imperial household faces the same challenges as all modern families. Rather than champion those issues, they try to hide their struggles.

As one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world — and the home to a generous welfare system — Japan has no choice but to encourage more women to remain in the workforce, even once they have children.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made empowering women one of his biggest rallying cries — and to his credit, he has elevated public acknowledgement of the issue to unprecedented levels. But his words have yet to lead to concrete results, as Japan ranks in 105th place on the World Economic Forum’s latest global annual gender gap report. Even more worrisome is the fact that one in three young, well-educated Japanese women still just want to get married and become full-time housewives, according the Japanese Health Ministry’s survey of women and their aspirations last September.

Emperor Hirohito may approve that such traditional values still remain strong under his son Akihito’s reign. But if Japan is serious about even getting closer to its glory days, it needs to accept the fact that the winning formulas that worked in the past simply won’t work in the future.

Hirohito’s successors can and must contribute to spur the much-needed social change.

* * *

Shihoko Goto is an Associate with the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, specializing in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. She was formerly a correspondent for Dow Jones News Service and UPI in Tokyo and Washington. Follow her on Twitter at @GotoEastAsia.