Fall 2014

Love/Hate: New York, Race, and 1989

Three events defined 1989 in NYC: the Central Park jogger attack, the murder of Yusef Hawkins, and the election of the city's first (and only) black mayor.

“THE FUTURE BELONGS TO CROWDS,” wrote Don DeLillo in his novel Mao II. It remains, in many ways, the perfect summation of the year that helped inspire DeLillo’s book: 1989.

In June, throngs of college students overtook Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in a rally for democracy; thousands were killed as the government crushed the demonstration. In the fall and winter, the Berlin Wall fell; communist rule ended in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania; and nationalist movements in the Baltics were both literally and figuratively chipping away at the Soviet Union. Iran, Greece, and South Africa all witnessed the election of reformist governments. A British scientist invented the World Wide Web, the first GPS satellite was launched, and an American company offered the public a dial-up Internet connection for the first time. For millions around the world, the events of 1989 seemed to open a road into an unknown but hope-filled future.

For New York City, the 365 days of 1989 were a curved bridge taken too fast from the violence of the 1970s to the prosperity of the 1990s. Gentrification acted like napalm on minority neighborhoods: clinging to whatever it touched, impossible to wipe away, igniting fires that burned fast and hot and often lethal. The haves and have-nots lived in uncomfortable proximity. Crime ran the streets of neighborhoods like Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant and Red Hook and Manhattan’s Harlem, fueled by cash, guns, and crack — the cheap, dangerous drug that had arrived a few years earlier and devoured the urban core. On an average day in 1989, New York suffered five murders, nine rapes, and 194 aggravated assaults. The city was in internal strife.

1989 in New York was a curved bridge taken too fast from the violence of the 1970s to the prosperity of the 1990s

For the City of New York, three events defined 1989, exposing the knotted ligaments of race, justice, crime, and power.

On April 19, a white female was assaulted and raped during a nighttime jog through Central Park. Five teenage males — all black or Latino, all from Harlem, all between the ages of 14 and 16 — were arrested, charged with, and convicted of the crime.

On August 23, a 16-year-old African American male was shot to death after being attacked by a crush of white youths in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

And on November 7, the city of New York elected its first (and to this date, only) African American mayor.

TWO REPORTED RAPES ON THE SAME NIGHT in April 1989 spoke volumes about how the media covered crime in the city.

In Bedford-Stuyvesant, a 38-year-old black woman was approached on the street by two men. At knifepoint, they forced her up to the roof of a four-story building, where they raped and beat her before throwing her 50 feet to the street below. She suffered two broken ankles, a fractured right leg, and abdominal injuries.

That same night, in Central Park, a 28-year-old white woman was jogging when she was violently assaulted — dragged off the running path, raped, and severely beaten. Her skull was fractured, and she almost died from blood loss. Days later, when she awoke from her coma, she had no memory of the attack nor of any events in the hour immediately before the assault.

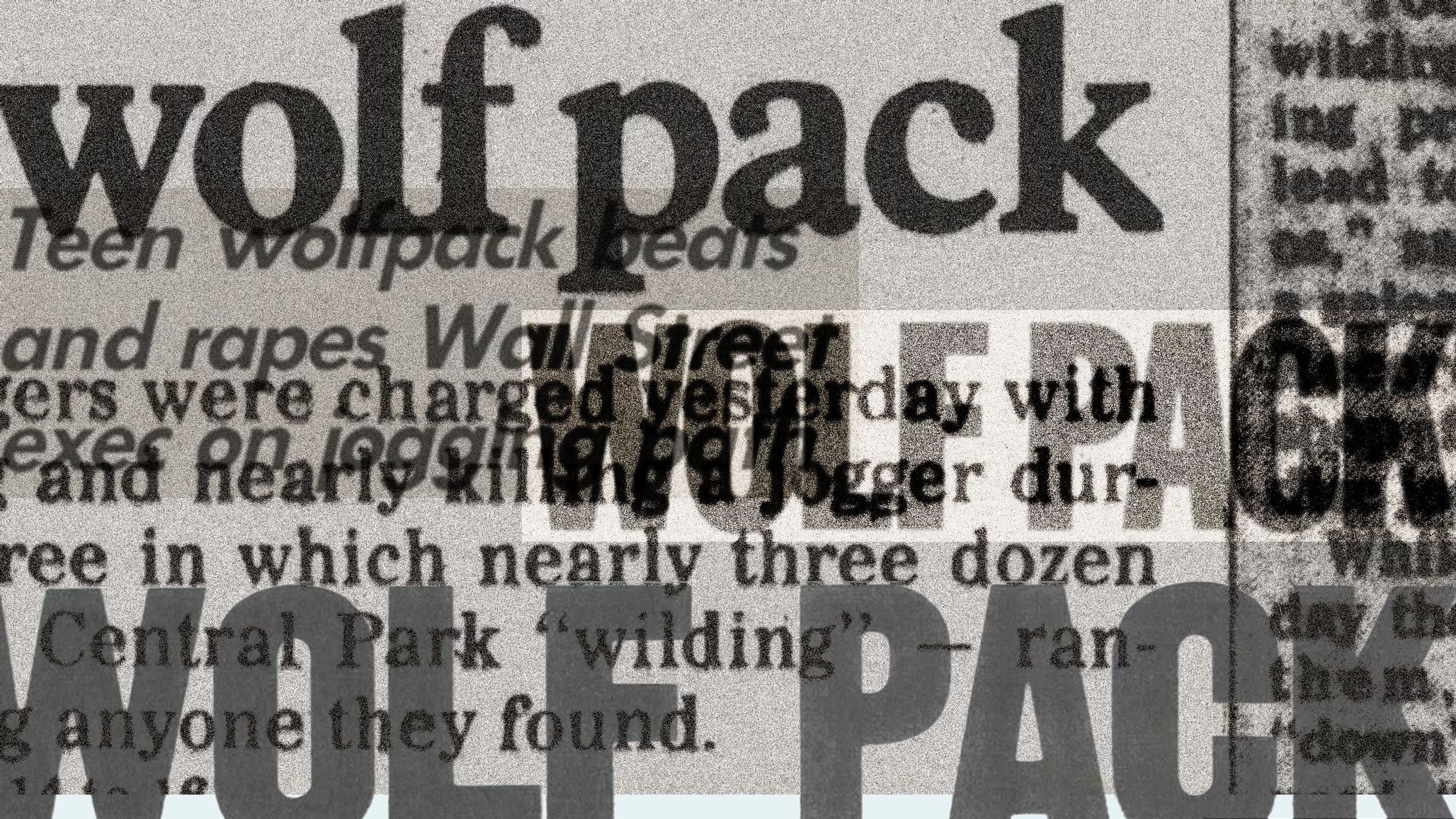

The first story was a brief flicker in the local, violence-loaded 35-cent tabloids. The latter became a national story, splattered across front pages for weeks, and introduced a new word — “wilding” — into the lexicon. New York City Mayor Ed Koch declared it “the crime of the century.”

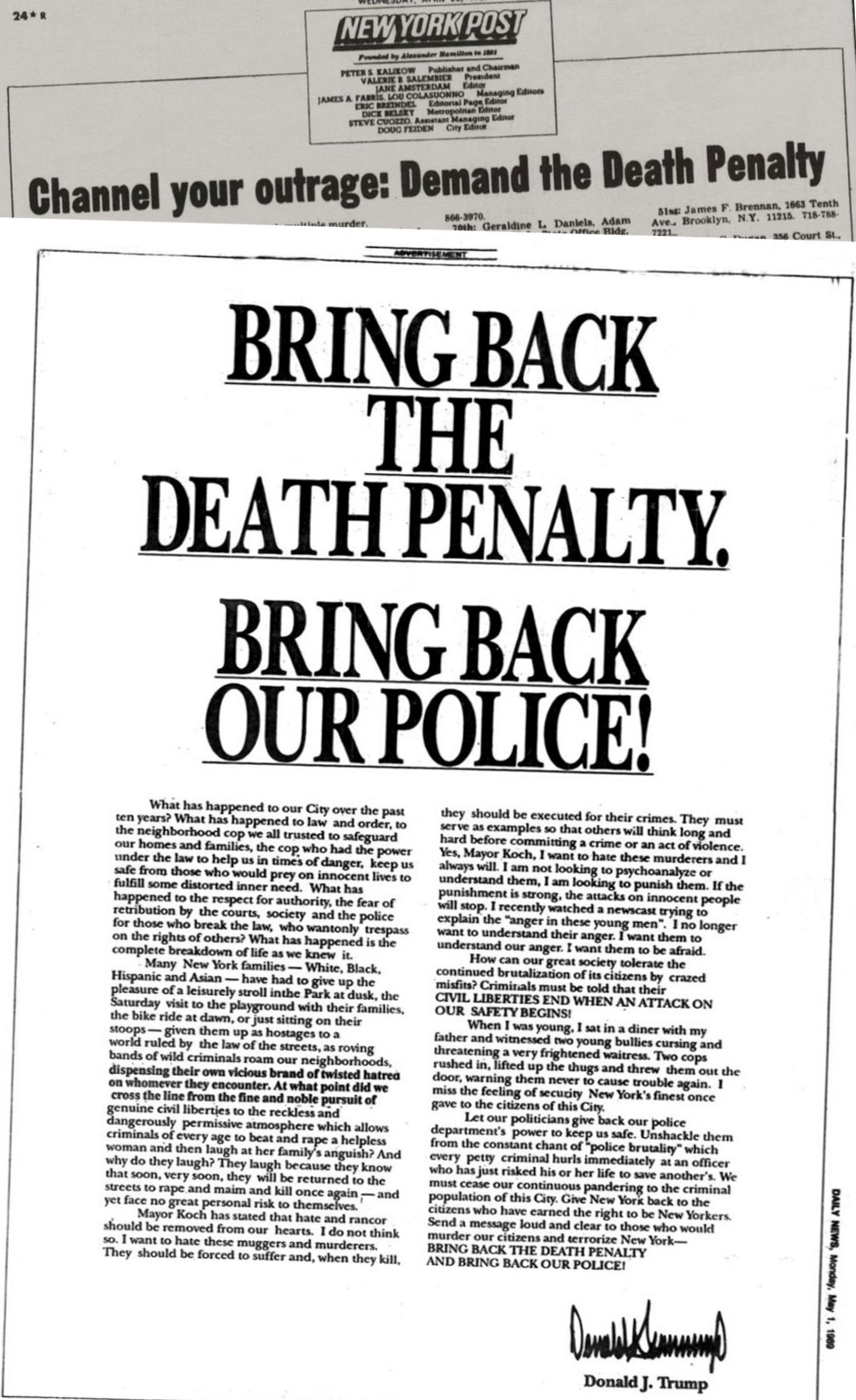

The brutal attack on Trisha Meili — the Central Park jogger — came to epitomize the fears of New Yorkers. The case, trial, and convictions were followed closely because the urbanites were afraid. Afraid to travel. Afraid to go to the park. Afraid to make their daily commutes. Afraid to live in New York. They needed someone to blame; they found what they were looking for in five young men whose names became synonymous with the city’s fear. The world came to know them as the “Central Park Five.”

The media depicted Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Korey Wise as violent, nihilistic teens. They were accused of being a part of a larger group of around 30 teenagers who were “wilding” — “street slang for going berzerk,” as one New York Daily News headline defined it — in Central Park on the night of April 19, 1989. The press called the boys a “wolf pack,” and accused them of a dozen assaults in the park before their attack on Meili.

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) was under tremendous pressure to close the case. Veteran detectives used well-worn techniques to mislead the young suspects and convince them to confess. After interrogating each of the teens separately for more than 14 hours, police turned on video cameras and taped the confessions. The defendants’ taped statements contained inconsistencies with each other and inconsistencies with the clues present at the scene. No physical evidence ever linked any of the accused to the crime.

None of that mattered. The court of public opinion reached a verdict before the criminal trials even began, and the justice system soon concurred. The five young men were found guilty. Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, and Raymond Santana were sentenced to five to ten years in prison; Korey Wise, age 16, was tried as an adult and sentenced to five to fifteen years.

In the weeks and months after the brutal rape, a media frenzy erupted. The case was prosecuted quickly and — in the minds of scared city residents — the police did their jobs. They had put the right people away.

The problem? The Central Park Five were innocent.

Two days after the attack in Central Park, the normally outspoken Mayor Koch released a statement. “I think that everybody here — maybe across the nation — will look at this case to see how the criminal system works,” he said. “How will this be handled? This is, I think, putting the criminal justice system on trial.”

From that day until today, the answer is the same: the criminal justice system was guilty. It failed by every measure. It failed Antron, Kevin, Yusef, Raymond, and Korey. It failed Trisha Meili. It failed — tragically so — the other victims of the real rapist, Matias Reyes.

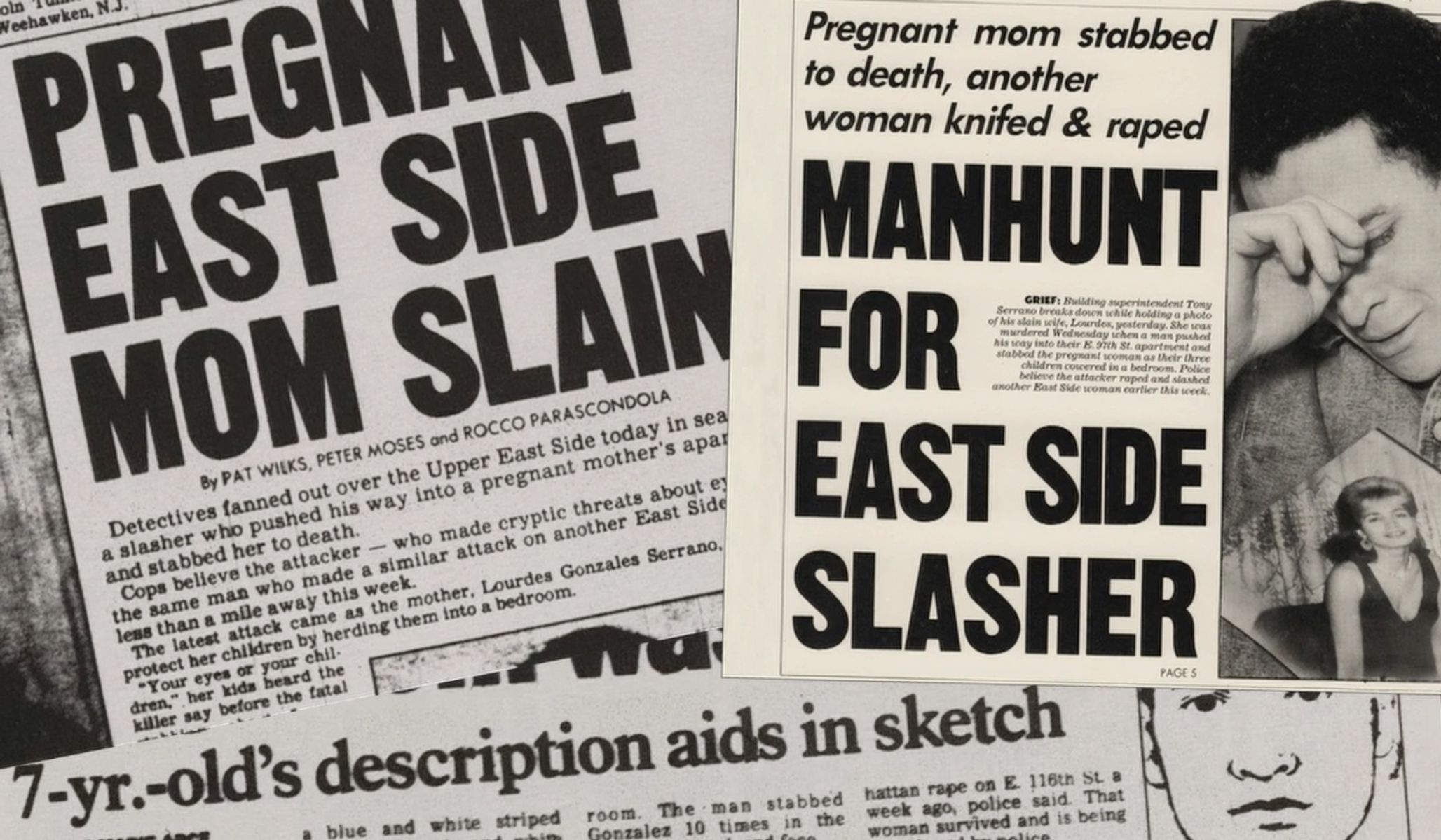

On June 14, 1989 — two months after the Central Park jogger attack, with the criminal justice system still focused on five innocent teens — Matias Reyes raped and murdered Lourdes Gonzalez, a pregnant mother of three. He stabbed her nine times as she begged him not to hurt her children, who listened to their mother’s screams from a different room in the apartment. Two months later, on August 5, Reyes was caught by an apartment building’s porter as he fled yet another crime scene, one of at least three rapes he committed between the Central Park attack and when he was finally apprehended.

Though Reyes had been identified as a suspect in a rape two days before he attacked Trisha Meili on her evening jog, no detective ever questioned him about the jogger attack. He wouldn’t be connected to it until May 2002, when he confessed to the crime — an admission of guilt that was prompted by a run-in between Reyes and Korey Wise in prison earlier that year. In December 2002, the convictions of the Central Park Five were overturned.

If this case was, as Mayor Koch said, “putting the criminal justice system on trial,” then there is no question: beyond any reasonable doubt, the prosecution, the police, and the press had failed the city. “The Central Park case will be one of the most important criminal cases in the history of the United States,” says Jonathan Zimmerman, professor of history at New York University. “The narrative of young black men being predators fit society’s preconceptions. It exposed the huge imperfections of the criminal justice system.”

Although much of the mainstream media regurgitated the preconceptions that had led to the wrongful conviction of the Central Park Five, others voiced their dissent — loudly.

SPIKE LEE’S FILM Do the Right Thing, released in June 1989, tells the story of stewing racial tensions in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. The film’s opening credits explode on to the screen with a tempest of a dance number set to “Fight the Power,” the newly released anthem by rap group Public Enemy. It was a call to action — “our freedom of speech is freedom or death, we got to fight the powers that be” — as Public Enemy frontman Chuck D demanded that people open their eyes to the racism around them and push back against it.

The film takes place over one scorching summer day, following more than a dozen characters — black, white, Puerto Rican, Korean, old, young, male, female, intellectually disabled — in Bed-Stuy as their lives repeatedly collide, with harmonious and hateful results. As the day wears on and tensions rise, Sal (the Italian-American owner of a local pizza joint) snaps, hurls a racial epithet, and provokes a brawl. The police are called, try to quell the fighting by force, and in so doing strangle to death Radio Raheem, a young black man known for his suitcase-sized boombox. A riot ensues. In the end, Sal’s pizza shop is burned to the ground, and we’re left to answer who, if anyone, did the right thing.

The movie was controversial, commercially successful, and went on to become one of the most critically acclaimed films of its era. Years later, it was selected in its first year of eligibility for the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry. A young Barack Obama took Michelle Robinson to see the film on their first date. “Do the Right Thing still holds up a mirror to our society, and it makes us laugh and think and challenges all of us to see ourselves in one another,” said President Obama in a video message created for the film’s 25th anniversary.

In June 2014, after a screening at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, director Spike Lee discussed the making of the film and its lasting impact. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library and a grandson of longtime Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, remarked that Spike Lee was reflecting the world around him. “Howard Beach. Yusef Hawkins. It’s Bensonhurst. It’s Mayor Ed Koch,” Lee replied. “Eleanor Bumpurs. Go on down the line. Michael Stewart. A lot of stuff was happening at the time in New York City.”

THREE WEEKS AFTER MATIAS REYES WAS BROUGHT INTO CUSTODY in August 1989, a different mob attack would grab the city’s attention — one perpetrated by a gang of roughly 30 white youths against a defenseless black teenager. Nobody called them a “wolfpack.” Nobody referred to it as “wilding.”

On August 23, Yusef Hawkins, a black 16-year-old, and three friends took the N train into Bensonhurst, a predominantly Italian-American neighborhood in Brooklyn. Hawkins came to meet the owner of a 1982 Pontiac. Yusef was hoping to purchase it for $900.

“This is a closed, insular world, this enclave in Brooklyn … a world of tightknit families and fear and hostility toward the outside,” reads a New York Times report from September 1989. A place “where the young men … grow up with a macho code.”

Throughout the day on August 23, rumors ricocheted through Bensonhurst, and innuendos quickly became imminent threats — that a neighborhood white girl was dating a black teenager, that she was inviting black and Latino boys to the neighborhood for her 18th birthday party that night, that a group of black teenagers was coming to beat up a white kid from Bensonhurst, that this neighborhood girl needed someone (or the whole community) to protect her honor.

As Yusef Hawkins and his friends searched for the address from the used car listing, they came across a mob of 30 or so angry white youths. “What are you niggers doing here?” shouted someone in the crowd. The white teens surrounded Hawkins and his friends. Some carried baseball bats. At least one carried a gun. Hawkins was holding a half-eaten Snickers bar.

Yusef Hawkins, trapped in a Bensonhurst doorway, was shot in the chest by a .32-caliber revolver. Two bullets cut through his heart. He slumped to the ground.

The white youths scattered. Eight of them eventually came to face charges, but Joseph Fama, age 18, and Keith Mondello, 19, were identified as the leaders of the mob, with Fama as the gunman.

Nobody called them a “wolfpack.” Nobody referred to it as “wilding.”

Hawkins’ murder was the latest in a long string of racially tinged deaths in New York City: Willie Turks in 1982, pulled out of a car and beaten to death in Gravesend; Michael Stewart in 1983, mysteriously dead from asphyxiation while in police custody for scrawling graffiti on the wall of the First Avenue L subway station; Eleanor Bumpurs in 1984, a 66-year-old woman with severe mental health issues, shot twice by police as they tried to subdue her during an attempted eviction; Michael Griffith in 1986, killed when he was struck by a car on Shore Parkway as he fled assault by a mob of 10 white men in Howard Beach, Queens.

Three days after Yusef Hawkins’s death, 300 black demonstrators marched through the streets of Bensonhurst. Neighborhood residents cursed and spat upon the protesters, hitting them with food. Some locals held watermelons. Organized shouts retched forward from the crowd, and the taunts varied: “niggers go home” or “useless” (a play on the victim’s name) or “Central Park, Central Park.”

Brooklyn native Reverend Al Sharpton, who organized the march, emerged as the controversial voice for the disenfranchised. He led demonstrations throughout the city, demanding justice while earning substantial coverage from a rapt media. Mayor Koch, meanwhile, condemned Sharpton’s protest in Bensonhurst: “It’s just as wrong to march into Bensonhurst as it would be to march into Harlem after that young woman in the jogging case.” Koch’s statement — which seemed to suggest that the comfort of whites in Bensonhurst trumped the need to memorialize Yusef Hawkins and protest his brutal murder — understandably enraged many in the city’s African-American population.

Amidst the controversy, Sharpton emerged as something of a spokesman for Hawkins’s family. Though few figures were as polarizing as 1989’s Al Sharpton, his interactions with the family seem more genuine than those of many other leaders. (In 1991, Sharpton would be stabbed by a white, drunk Bensonhurst male resident en route to another march through Bensonhurst in memory of Yusef Hawkins.)

Whereas Koch’s response to the protests looked at the murder through the unsympathetic prism of the feelings of Bensonhurst’s white population, Reverend Jesse Jackson’s response was arguably worse. With the forthcoming Democratic primary contest between Mayor Koch and his black challenger David Dinkins occupying a significant portion of the media’s attention, the New York Daily News (among other outlets) reported that, while Sharpton was sitting with the grieving parents at their son’s wake, Jackson approached them and said, motioning to the casket, “That boy lying in there could make David Dinkins the next mayor.” Moses Stewart, Yusef Hawkins’ father, flew into a rage. Though Jackson’s office later denied using those words, Stewart confirmed the story to reporters.

On Election Day, Moses Stewart stayed home. “It won’t make any difference,” he told Newsday’s Jimmy Breslin.

A FEW WEEKS AFTER THE MURDER OF YUSEF HAWKINS, David Dinkins, the sitting Manhattan borough president, defeated three-term incumbent Ed Koch in the Democratic mayoral primary on his way to becoming New York City’s first black mayor.

From the start of the campaign, Dinkins portrayed himself as a salve for the city’s racial wounds — “a man of hope and healing,” as Jesse Jackson called him at a campaign rally. “I am running because our city has become sharply polarized,” Dinkins told his supporters at his announcement speech in February 1989. “We need a mayor who can transcend differences so we can work together to solve our problems.” Mayor Koch, by contrast, was painted as a man who, if not the source of the city’s worsening racial dynamics, was either unable or unwilling to take the issue seriously. “For every New York program and every New York pain,” ran one Dinkins radio ad, “[Koch] has a joke, a wisecrack, a one-liner.”

“African Americans had more of a governmental voice in D.C. than in New York City,” says New York University professor Jonathan Zimmerman. “Harlem was the basis of political power. African Americans didn’t have the dominance in population like in other American cities. Philadelphia, Cleveland, D.C., and others had large black populations and a history of black mayors by that time. New York doesn’t have the concentration.”

Lacking a demographic edge, there were two major factors in Dinkins’ mayoral win: a Democratic establishment severely weakened by corruption scandals, and the successful fusion of a diverse array of voters. “Although few realized this at the time, Dinkins benefited most from the 1986 criminal indictment and prosecution … of Democratic political leaders in the Bronx and Queens,” wrote J. Phillip Thompson in his 1990 analysis of the Dinkins election. The rat-a-tat of prosecutions — which, as fate would have it, were led by U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani, Dinkins’s future opponent in the 1989 and 1993 mayoral elections — took down three congressmen and one borough president.

For Mayor Koch, the political damage was almost incalculable. The machinery of the Democratic establishment — so instrumental in securing his three terms in office — was self-destructing, and the public increasingly saw Koch as complicit in the corruption. Black and Latino politicos, free from the bonds of political patronage and newly able to speak out without the fear of retribution, stepped in to fill the party’s power vacuum, hammering the mayor over the city’s ongoing racial tensions. In 1988, the Black-Latino-Labor alliance delivered a crushing blow to Koch with Jesse Jackson’s victory in New York City’s 1988 presidential primaries. “Jackson’s 1988 presidential campaign [was a] testing ground for the 1989 Dinkins mayoral candidacy,” wrote Thompson. “Given that a black or Latino candidate had never won a citywide election in New York City, Jackson’s victory was widely perceived as a momentous gain for black New Yorkers.”

To become mayor in 1989, Dinkins would have to unseat an incumbent three-term mayor in a primary. Then he would advance to a general election campaign against Rudy Giuliani, the charismatic federal prosecutor known for his enormously high conviction rate and success against high-profile criminals like mafia kingpin John Gotti. Giuliani had the support of both the Republican and Liberal parties, and Dinkins knew that his own victory could not be won solely on the back of the city’s new Democratic coalition. He had to appeal to the city’s white and Jewish voters without alienating the black supporters who were enraged by the city’s racial violence. He denounced controversial Nation of Islam minister Louis Farrakhan for anti-Semitism. He used Jesse Jackson at campaign rallies, but was careful to distance himself from the reverend in other areas. He urged calm after the brutal murder of Yusef Hawkins in Bensonhurst, but demanded swift prosecutions for those responsible. He said the Central Park Five were guilty of “urban terrorism,” that the city was “under siege,” and that harsh penalties needed to be doled out immediately. His positions were an indication of the political and social strains that the events of 1989 had put on the city and its residents.

Dinkins handily defeated Koch in the September primary. Exit polls showed he won 9 in 10 black voters; picked up about one-third of white voters (twice the support that they had given to Jesse Jackson one year earlier); and kept the margins small in Koch strongholds such as Staten Island and Manhattan’s West Side. His appeal as the candidate for racial harmony worked: 6 in 10 white voters thought he would be fair to both blacks and whites, while 7 in 10 black voters believed that Mayor Koch gave preferential treatment to whites.

Though Dinkins proved victorious in the general election, in the November mayoral election he defeated Giuliani by only three percentage points. “Two-thirds of the whites and 9 of 10 blacks voted for a candidate of their own race,” reported the New York Times. It was among the closest New York mayoral races in a century.

The election of David Dinkins set into motion the defining dynamic of the next two decades of mayoral politics in the city: As black and Latino leaders rose in the Democratic Party, white ethnic New Yorkers fled it. Roughly 60 percent of Koch’s primary voters defected to Giuliani in the general election. Bensonhurst, where Dinkins had been so careful to urge calm, went to Giuliani by a 10 to 1 margin.

“I know that your faith in me is not going to fade away,” Giuliani told his supporters on election night. “I assure you, I’m not going to fade away.”

Four years later, David Dinkins lost reelection to Rudy Giuliani. He would be the last Democratic mayor in New York City for 20 years.

ON JULY 17, 2014, ERIC GARNER, a 43-year-old black man and resident of Staten Island, was approached by two plainclothes NYPD officers who questioned him about selling “looseys” — untaxed cigarettes. The confrontation between Garner and the police escalated until Officer Daniel Pantaleo put Garner in a chokehold and three other officers helped take Garner to the ground. Garner died.

Four days later, filmmaker Spike Lee tweeted out a link to a video titled “Radio Raheem and the Gentle Giant.” It mixes the footage of Garner’s death with footage from the death of Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing. The similarities are eerie. Contrasted with the scenes of Radio Raheem losing his struggle against a police officer’s chokehold are Garner’s screams: “I’m minding my business, please just leave me alone!” After he’s forced to the ground, Garner gargles and cries, “I can’t breathe! I can’t breathe! Get off of me! Get off of me!”

New Yorkers, then and now, hold onto the hope that times have changed, but we have to consider the possibility that while much has changed, for many New Yorkers — particularly in less-affluent or minority neighborhoods — change has been slow to come, and when it has, it hasn’t always meant improvement.

FAST-FORWARD A QUARTER-CENTURY FROM 1989. Raymond Santana — sentenced at age 14 for a crime that he and the other members of the Central Park Five didn’t commit — and I sit on a warped wooden bench on a hot July night in Bryant Park, the green blip in the middle of Midtown Manhattan. The cheers of World Cup fans and laughter of children fills the air around us.

“It’s hard not to think about how it happened 25 years ago,” he says. Santana is now 39. He wears athletic shorts and a gray shirt, having just come from a gym. He has a goatee, but still comes across as incredibly youthful — and sincere.

“Would you ever leave this city?” I ask.

Raymond Santana is a proud man — fearless, well-read, tireless — who has rebuilt his life with quiet dignity. He’s also a victim — of racism, of media sensationalism, of the criminal justice system. A victim in every way.

“No. I couldn’t leave,” he says. “It was a battle. I had to stay. I had to fight by telling my story. By doing the book with Sarah [Burns]. By doing the movie with Ken [Burns] and David [McMahon]. Getting the Central Park Five story out there — the real story — was all due to the book, the film, by going out to speak to kids.”

On our way to the park from the Midtown gym where he used to work as a personal trainer, we run into friends and supporters congratulating him on the $40 million settlement that the city agreed to pay to the Central Park Five.

“Raymond! I’m so happy for you,” says a smiling man as we leave to go down the street.

A middle-aged woman stops and practically knocks him over. “Raymond!” she says, beaming. “You deserve every penny. I had no idea that happened to you. Congratulations!”

You can see that he’s happy. The crowds that greet him are no longer angry. They welcome him.

He is no longer infamous. He is no longer anonymous. He isn’t alone.

He will never leave the city, and New York will never leave him.

* * *

Garrett McGrath is a contributor to Narratively and Uni Watch. Follow him on Twitter at @garrettpmcgrath.

Additional contributions by Zack Stanton.

Created in partnership between The Wilson Quarterly and Narratively.