Summer 2013

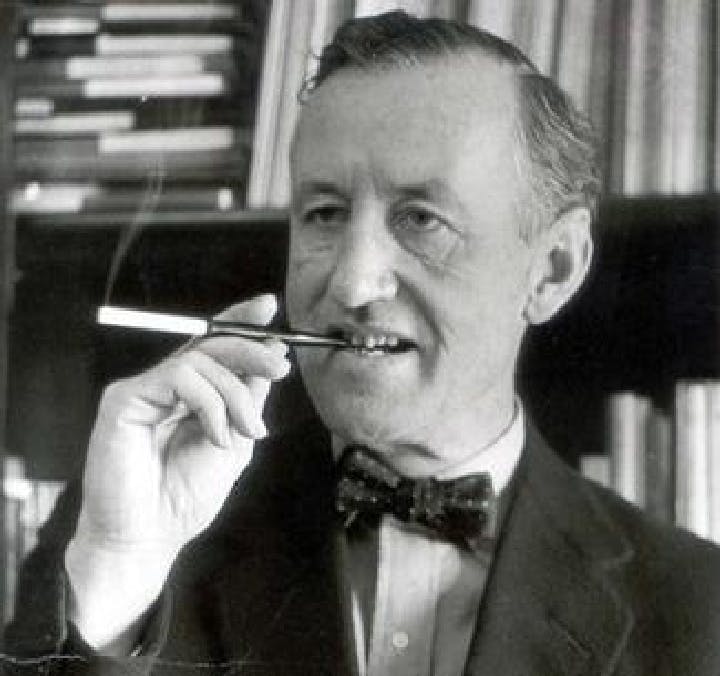

The CIA’s favorite novelist

– The Wilson Quarterly

From Fleming with love.

British superspy James Bond is in a bad way. He’s out of chips in a crucial game of baccarat against le Chiffre, the Soviet agent in France. Will a bad guy best the free world?

Not if the CIA can help it. Agency man Felix Leiter swoops in with a wad of cash and a note to 007: “Marshall Aid. Thirty-two millions francs. With compliments of the U.S.A.”

For many American readers of Casino Royale (1953), Ian Fleming’s debut Bond novel, this was the first time they’d heard much of anything about the Central Intelligence Agency. Journalists did not dare pull back the veil of secrecy surrounding the organization, established in 1947 as part of the National Security Act. Even to utter its name on television required permission — and the CIA never granted it.

That didn’t stop Fleming (1908–1964), the British novelist and former intelligence officer who wrote his 14 smash-hit Bond books outside the United States. Fleming “could say what he liked about the agency,” writes Christopher Moran in the Journal of Cold War Studies. “The Official Secrets Act in Britain prevented him from mentioning explicitly that James Bond, his hero, worked for the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), but nothing prevented him from linking Leiter, the American sidekick, to the CIA.”

So it was that for the first 25 years of the CIA’s existence Fleming almost singlehandedly shaped the popular perception of America’s spy agency. “In the main, his depiction was positive,” Moran judges. Fleming won powerful American friends and fans in the process, including President John F. Kennedy and his family.

The Bond series, which was published between 1953 and 1964 and has sold more than 100 million copies to date, paints American spies as courageous cold warriors, if a bit clumsy. (The first Bond film, Dr. No, appeared in 1963 and was based on the 1958 novel.) Felix Leiter is a consummate professional: cool under pressure, hard as nails, and fiercely patriotic. Leiter’s CIA, while always playing second fiddle to Bond and the British, receives treatment a spin doctor would envy. “In Fleming’s hands, the CIA is shown to be a force for good in a dangerous world,” explains Moran, a professor of U.S. national security at the University of Warwick in England. That picture stands in contrast to portrayals by later spy novelists, such as John le Carré, the Briton who has depicted Agency men as paranoid and amoral.

Why all the warm feelings from Bond’s creator? As personal assistant to the director of British Naval Intelligence during World War II, Fleming developed a “genuine fondness” for American spooks. On trips to the United States during the war, he witnessed British and American spies working side by side at British Security Coordination, a New York–based outfit set up by UK intelligence “to combat Nazi propaganda and to gain the sympathies and cooperation of the U.S. public.”

In Washington, Fleming left a deep impression on General William J. Donovan, the redoubtable head of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the CIA’s predecessor. The legendary “Wild Bill” was “captivated by Fleming’s high spirits, lively tongue, and unorthodox methods, seeing him as an exemplar of the swashbuckling and slightly eccentric British secret service tradition.” Fleming played the part. He traveled to the States wearing a commando fighting knife and packing “a fountain pen loaded with a cyanide cartridge.” Donovan reportedly asked the future novelist to help draw up plans for a postwar spy agency (what would become the CIA), and later presented Fleming with a .38 Colt revolver. The inscription: “For Special Services.”

Fleming returned the favor by using Donovan’s hard-charging personality as his model for the fictional Leiter, a “tough and cruel fighter” who entered Agency service out of the U.S. Marine Corps.

It was an apt portrait. During the 1950s and ’60s — the “golden age” of CIA covert action, when neither Congress nor the press pried into the spy service’s doings — Agency operatives hopscotched the globe on daring — and sometimes dubious — missions.

But Fleming stuck to a feel-good script. “No mention is made of intelligence failures, nor does Fleming discuss any ‘dirty tricks’” — assassination plots, experiments with mind control, and coups against democratically elected leaders.

Little wonder that Allen Dulles, director of the CIA from 1953 to 1961, couldn’t get enough of Bond. In 1957, he received a copy of From Russia With Love, published that year, from Jacqueline Kennedy — John and Robert Kennedy were huge Bond fans. Dulles, an OSS veteran, sang Bond’s praises in the press and in retirement attended debuts of the film adaptations. In 1959, British spies arranged for Dulles to meet Fleming in London. Fleming dazzled Dulles with his wit and imagination, especially on the subject of spy gadgetry. Back at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, Dulles leaned on his underlings “to replicate as many of Bond’s devices as they could.”

The two men struck up a profitable friendship. Fleming sent Dulles signed Bond books. Dulles, who resigned from the Agency in 1961 in the wake of the Bay of Pigs disaster, sent Fleming an early draft of his memoir, The Craft of Intelligence (1963). In turn, Fleming included an increasing number of flattering allusions to the CIA in his novels. In The Man With the Golden Gun (1965), Bond convalesces from a fight thusly: “sitting in his chair, a towel round his waist, reading Allen Dulles’s The Craft of Intelligence.” And Fleming benefited handsomely when Dulles talked up 007, as he did at a 1963 meeting of the American Booksellers Association.

Despite his affinity for Americans, Fleming stayed true to his British roots. The Bond novels leave no doubt that Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service plays the game better than anyone. The CIA provides funds and logistics while 007 outsmarts and outfights the Soviets. In Casino Royale, it’s Bond who is tasked with cleaning out le Chiffre, even though this “should have been a problem for the French or for the Americans to deal with,” according to Moran. Though Leiter saves Bond from baccarat bankruptcy, he spends most of the novel attending to less glamorous chores, “such as completing the necessary paperwork for back home,” Moran writes.

In Live and Let Die (1954), Felix snoops around without Bond’s guiding hand and makes a fool of himself. Instead of seducing women and cultivating local agents, as 007 does, Felix relies on paid informants for intelligence and winds up getting captured. Fed to a shark, he barely escapes with his life. Fleming drives the message home in Diamonds Are Forever (1956). “Whereas Bond — the Briton — appears impeccably attired and athletic, radiating sex appeal, Leiter uses crutches, walks with a limp, and wears a prosthetic hook,” Moran writes.

In reality, the British were the ones limping. Smarting from colonial losses and financial problems at home, SIS could hardly keep up with the Americans. “In real life the CIA was primus inter pares,” Moran observes. “SIS was impecunious, operationally more cautious, and incapable of matching the resources of its closest collaborator.”

Fleming’s depiction of Anglo-American bonhomie also misses the mark. CIA men, including Dulles, saw SIS as overly class conscious and susceptible to Soviet infiltration. One American spy of the era said the CIA viewed its British counterparts as a “bunch of supercilious snobs” who wouldn’t protect the goods. “Don’t tell the bastards anything,” the refrain went.

Yet the Yanks couldn’t shake their affinity for Fleming. In a 1961 story for Life, John Kennedy put From Russia With Love on a list of his 10 favorite books. At a Georgetown dinner party, Kennedy, then a presidential candidate, enthusiastically sought Fleming’s input on how to depose Cuba’s Fidel Castro. The novelist shot from the hip, mentioning harebrained schemes to humiliate Castro and convince Cubans of divine opposition to his regime. Kennedy laughed at the suggestions. But Dulles, who caught wind of Fleming’s musings, seized on them. The CIA’s campaign to topple Castro, Operation Mongoose, included stunts that bore a resemblance to some of Fleming’s ideas. The British novelist with a wild imagination “may have played a part in encouraging the CIA down the path of fantasy,” Moran ventures.

Whatever else Fleming did, he warmed a reticent CIA up to the idea of good PR. “There are tantalizing hints, albeit nothing conclusive, that by the early 1960s the CIA was directly trying to influence Fleming’s coverage of the agency.” In 1961, Fleming told a New York Times journalist that Dulles’s “organization and staff have always cooperated so willingly with James Bond.”

Langley left everyone else in the dark. The CIA didn’t open up to mass media until the 1970s and ’80s, when “ugly revelations — amplified and distorted at the hands of novelists and filmmakers — convinced a new generation of intelligence officials that the CIA had an image problem and that popular culture could help.” But once upon a time, Bond had been all the Agency needed.

THE SOURCE: “Ian Fleming and the Public Profile of the CIA” by Christopher Moran. Journal of Cold War Studies, Winter 2013

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia