Winter 2018

The Disinformation Vaccination

While many have woken up to the realities of Russian disinformation, responding to Moscow and censuring social media cannot be the end of the story. Instead, the U.S. should take a long, hard look in the mirror and invest in its own citizens.

The most illuminating conversations I’ve had about Russian disinformation have not been with ex-Cold Warriors, Russia hands, or government officials. They have been with the people that – according to many of those I just listed – are purveyors of disinformation themselves.

“I don’t believe in fighting [against] information. That’s what the communists did,” Jaroslav Plesl, the editor-in-chief of Dnes, the Czech Republic’s second-largest daily newspaper, told me in January 2017, just after the Czech government unveiled a new center to fight terrorism and so-called “hybrid threats,” including disinformation.

I caught a lot of flak for publishing a quote from that conversation in an editorial on how to fight fake news. A Czech friend in the anti-disinformation field told me that while he didn’t think Plesl was on the Kremlin payroll, he might as well be, given all he and his publication do to amplify the Russian state’s narratives.

My friend won’t be happy to find out that on my last trip to Prague, I met with an editor at Parlamentní Listy, one of the most popular fringe media outlets in the country. It is often accused of having Kremlin ties. Whether or not that’s true, Jan Rychetský, the editor with whom I spoke, described his employer’s strategy very simply: “We try to speak to the people that no one from the mainstream media speaks to.”

It is critical that we think not only in terms of a direct response to Russia, but a reaction to the greater shifts in our society and, in some cases, societal failures, that allowed Russian meddling to become so effective.

These comments aren’t unique to the Czech Republic, or even to Eastern Europe. They’re endemic to the increasingly polarized, distrusting societies that have emerged around the world, including in the United States. They speak to the heart of the reason the U.S. and its allies have found themselves scrambling to mount a response to Russian information warfare: in our new efforts to fact-check, to ferret out any whiff of Russian influence on social networks, and even to somehow seal our information environment from nefarious influencers, we’re still neglecting to protect the people most susceptible to the Kremlin’s narratives and overlooking much of why they’re particularly vulnerable. By extension, we’re neglecting to protect our democracy itself.

Now that we have woken up to the realities of this hostile foreign influence and are beginning to mount a defensive, it is critical that we think not only in terms of a direct response to Russia, but a reaction to the greater shifts in our society and, in some cases, societal failures, that allowed Russian meddling to become so effective.

An Invasive Species

Russia has been dealing in disinformation for decades. What differentiates its modern campaigns from those of the past are two characteristics: they now rarely promote a strictly pro-Russian narrative, choosing instead to stoke known tensions in a given society, and they are amplified by modern technology and the rapid spread of content on the internet. Both characteristics meant that the seeds of disinformation Russia planted around the 2016 election found an ideal climate in which to become an invasive species.

In October 2016, just 19 percent of the U.S. population trusted the government always or most of the time, a statistic that had suffered a precipitous decline since the September 11 attacks, according to Pew Research Center. The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, a survey of 28 countries, declared that “trust is in crisis around the world,” including in the United States, which had the largest trust gap between the “informed public” and the “mass population” regarding the institutions of government, business, media, and NGOs.

The decline in trust correlates with the shrinkage of the media landscape, with circulation of daily newspapers falling by more than 20 million over the past 20 years. Some of that drop can certainly be attributed to newspapers’ increased web traffic, but the quality of this traffic is disputable; in 2016, the average visit to such a site was less than two and a half minutes. Meanwhile, only one in five Americans place “a lot” of trust in national media and two-thirds of the country gets at least some news from social media.

Russia seized upon this widespread suspicion of our country’s democratic institutions to further exploit the fissures in our societies. Its infamous Facebook ad-buys covered polarizing issues of all stripes, from gay rights to Black Lives Matter to Civil War nostalgia. Most were accompanied by inflammatory images. What some Americans found in these ads and in other Russian-sponsored influence campaigns were messages that resonated with them, ostensibly unlike the content in the so-called “mainstream media.”

A similar dynamic contributed to the increasing popularity of Czech “alternative news site” Parlamentní Listy. In discussing mainstream outlets, Rychetský told me, “Suit journalism doesn’t suit me.” He lamented the issues covered and methods used by mainstream reporters. "They never work in the garden. They never speak with the old people. They never have beer in the village pubs.”

This professed approach, of course, does not condone or justify that the Russian efforts and outlets including Parlamentní Listy have pushed outright lies – so it’s understandable why a slew of NGOs, think tanks, and awareness-raising campaigns have embarked on fact-checking crusades, seeking to debunk the untruths published on disinformation sites that have cropped up on both sides of the Atlantic.

Beyond Band-Aids

The utility of these efforts, however, is unclear. Since the 1970s, psychological research has shown that repeated untruths are difficult to debunk. Add this to the recklessly amplifying Internet ecosystem on platforms like Twitter, in which “false information... overpowers efforts to correct it by a ratio of about three to one,” according to a study by Columbia University’s Andrew Guess. Fact-checking suddenly looks less like the panacea that many in the West seem to think it is.

The United States has also begun a regulatory battle against disinformation, even compelling Russian state-funded propaganda outlets RT and Sputnik to register as foreign agents. Russia responded by using whataboutist rhetoric to justify the reciprocal registration of Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty as foreign agents within the country.

It’s a harder, longer process, but one that seeks to move beyond band-aids and vaccinate against the virus, prioritizing the citizens who fall victim to disinformation.

But governments cannot simply fact-check or label their way out of the crisis of truth and trust that leads people to seek out sources like Parlamentní Listy or RT. The solution is likely not as technologically sexy as a new algorithm to weed out disinformation from social media, or as quirky as an army of “Baltic elves” who fight Russian trolls online. What we need is something familiar to many who have worked in foreign assistance: capacity-building. But rather than mounting such an effort abroad, we should pursue it for our own people. It’s a harder, longer process, but one that seeks to move beyond band-aids and vaccinate against the virus, prioritizing the citizens who fall victim to disinformation.

Two countries with a long history of responding to hostile information campaigns have come to this conclusion. Both have been testing grounds for citizen-focused responses to disinformation, and both have enjoyed a degree of success that merits analysis – and emulation – in the wider West.

The Finnish Model

Jed Willard tells an excellent story. As the director of the FDR Center for Global Engagement at Harvard University, he is often the lone academic among policy wonks. When I met him at a conference on strategic communications in Prague last May, he was surrounded by a gaggle of participants angling to chat with him; his presentation on what should have been a mundane discussion of future research trends in the anti-disinformation field was so captivating that he had suddenly become the conference’s most sought-after attendee. Willard had advised the Finnish government on the development of a public diplomacy program that focused on telling the country’s story instead of responding directly to Russian lies. The program is now finishing its third year.

In part, Finland was ahead of the Russian disinformation curve thanks to decades, if not centuries, of experience responding to hostile narratives peddled by its much larger neighbor. “The Finns are used to this,” says Willard. As a result, the government was able to “recognize similar efforts, now powered in part by social media, earlier than most other states.”

But it wasn’t just time the Finns had on their side. “Rather than responding to disinformation with impatient acrimony and gut-instinct,” Willard tells me, “the Finns have made a concerted effort to educate their military, civilian, and journalistic leadership on the social science behind it,” empowering officials to make more strategic decisions, and ultimately, produce a more compelling public narrative. “They didn't look for purely technical solutions or quick fixes, as some other states have.”

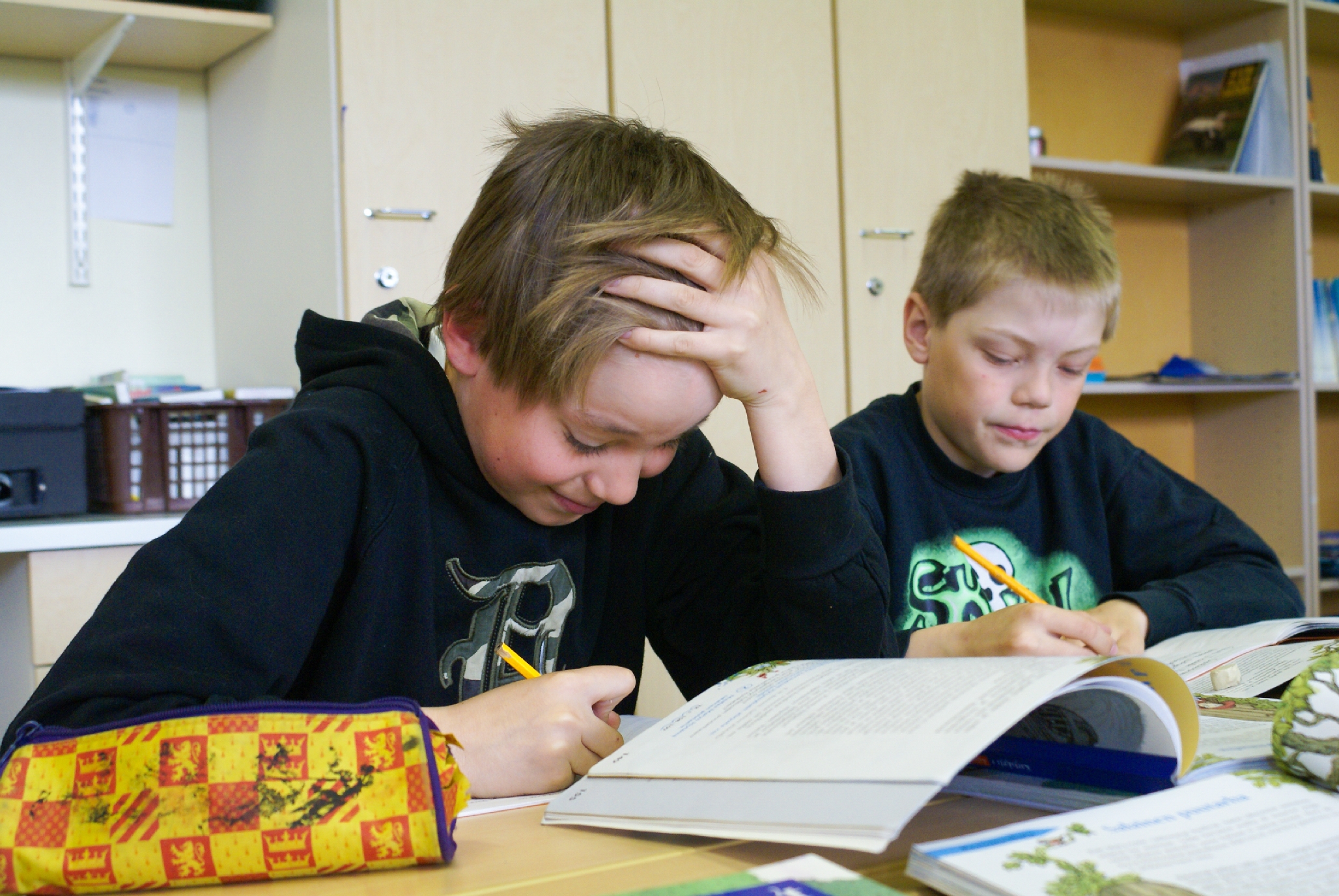

Beyond storytelling, the Finnish government equips even its youngest citizens with tools to survive in today’s crowded media environment. The government has viewed “media and information literacy” – which is predicated on critical thinking – as a “civic competence” since the 1960s. “We all need media literacy skills in our different roles in the information society: as citizens, consumers, employees and students,” wrote the Finnish minister of culture and sport in 2013. As such, in Finland, media literacy is a whole-of-government affair; in addition to the Ministry of Culture and Sport, the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Ministry of Justice, and the Finnish Competition and Consumer Agency, among others, contribute to the government’s policy.

Surely, Finland’s holistic view of media literacy will go far towards ensuring that society remains resilient in the face of whatever hostile information – Russian or otherwise – is directed towards it.

The policy is also radically inclusive, recognizing that “the child’s relationship with media may begin as a baby, for example on the lap of a parent who is using the internet,” and becomes stronger as children grow older and begin to use media to play, learn, and socialize. Finnish officials often refer to schools as Finland’s “first line of defense” against disinformation and the country’s education system is “frequently cited as a superpower of sorts,” according to Willard. Surely, Finland’s holistic view of media literacy will go far towards ensuring that society remains resilient in the face of whatever hostile information – Russian or otherwise – is directed towards it.

Whether this approach can be replicated in the United States is uncertain. The Finns enjoy a smaller and more homogeneous society – and therefore a clearer and more prevalent national narrative – as well as a nimbler governmental structure, which makes a whole-of-government response to disinformation easier to mount.

Learning to Discern

A larger and more diverse population, however, has not stopped NGOs and government actors in Ukraine from pursuing media literacy.

In 2016, 20 million people viewed a television ad that was a bit peculiar for the Ukrainian information environment, typically replete with commercials for medicines, upcoming shows, and beauty products. What they saw was an army of grocery shoppers selecting products from shelves without looking at them, while one woman took time to look at the nutrition label on each box. “Information is like a product,” intoned the voiceover. “It can be poor quality, incomplete, or even harmful. So what do you consume? High-quality [products], or something that only looks it? Be careful! Consume wisely!” Polling that measured the ad’s effect showed a 14-percent increase in viewers who recognized a need for knowledge and skills to separate truthful information from lies.

This public awareness campaign was a component of “Learn to Discern,” a pilot media literacy project implemented by IREX, a Washington-based NGO. The program, which “helps citizens detect and decode misinformation and propaganda,” developed a first-of-its kind curriculum for media literacy in the digital age.

“Traditional approaches to teaching media literacy haven’t evolved with the rapidly changing information space we live in today,” says Myahriban Karyagdyyeva, director of programs at IREX’s Kyiv field office. “With the advent of the internet and social media, individual citizens are now ‘news’ outlets themselves.”

Karyagdyyeva describes the curriculum, which was developed in partnership with the Academy of Ukrainian Press and StopFake, an Ukrainian fact-checking organization, as “less academic and more practical,” focusing on increasing consumers’ ability to recognize emotional manipulation – a tactic used by bots, savvy advertisers, profit-motivated publications, and yes, Russian propagandists.

Russian disinformation is often “colorful [and] emotionally charged” and “media literacy courses, by and large, failed to address this evolution,” according to Karyagdyyeva. IREX sought to “equip citizens with techniques for recognizing their own emotional reactions so they can read news more critically.”

Svitlana Zalishchuk, a young member of Ukraine’s parliament and a former journalist, agrees: “Communication is one of the most important dimensions of our life… but we don't know anything about the rules, about how to do it, how to protect ourselves,” she recently told me in Kyiv. “It has to be part of education, without a doubt.”

The IREX training program reached 15,000 Ukrainians, 92% of whom reported checking their sources three months after finishing. Though that’s a fraction of the country’s population of 45 million, the program offers a model that might be replicated more broadly at this particularly critical time (Ukraine is battling Russia and its proxies not only in the information space, but on the ground in the east). Last summer, the Ukrainian Ministry of Education signed a decree prioritizing media literacy in the national curriculum. As the war enters its fourth year, IREX is starting a second pilot program using its curriculum in Ukrainian schools.

Civic Investment

Today, the disinformation debate centers on Russia and its interference in the recent U.S. presidential election, and naturally, so does our response. But we must think deeper. We must think longer-term. Most of all, we must think not about a Russian bear lurking in every dark corner of the internet, but about our fellow citizens.

To prepare for these future attacks on democracy – and indeed, even attacks from within – we must think beyond Russia to the key actors in the democratic process: people.

Some members of Congress, in attempting to move the disinformation discussion away from the partisan rancor that has often characterized it, have warned that responding to this challenge is really about defending our democracy. They are absolutely right, but the policies that have resulted from these discussions are almost entirely directed at Russia. Moscow will continue to attempt to influence our democracy, as it has for decades, and now that the Kremlin has written the textbook for how to do so, other bad actors will undoubtedly imitate Russian tactics. To prepare for these future attacks on democracy – and indeed, even attacks from within – we must think beyond Russia to the key actors in the democratic process: people.

Thomas Jefferson recognized this, writing in 1820: “I know of no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education.”

Our best defense against hostile influence, whatever its vector, is to invest in critical thinking skills at all levels of the population so that outlandish claims are seen for what they truly are: emotional exploitation for political or monetary gain. Fringe outlets like the Czech Republic’s Parlamentní Listy existed before Russia exploited the arguments on their pages, and they will continue to grow and thrive unless deprived of the oxygen that first enabled them.

***

Nina Jankowicz (@wiczipedia) was a 2017 George F. Kennan Fellow at the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute and is an expert on Russian disinformation. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Project Syndicate, among other outlets.

Cover image courtesy of Shutterstock