Fall 2018

We Need a New – and True – Wilsonianism

– Trygve Throntveit

No, the world order Wilson envisioned will not survive – for contrary to historical memory, it has never been brought into existence. Provided such an incarnation, democracy’s declining practice might indeed be reversed.

These days, talk about the state of democracy globally, and of the United States’ role in its promotion or decline, is simultaneously cacophonous and monotonous. On one hand, we see major publications like The Atlantic devoting near-entire issues to some version of the question “Is democracy dying?” and find most contributors answering “yes” – for a disturbing array of reasons: Americans are urged to heed frightening signs from Europe regarding the frailty of democratic habits and institutions under tribalist pressures, not unlike those now straining American society. They are warned that the digital revolution favors tyranny rather than human agency, political equality, and free markets. At the same time, racism rapidly erodes America’s capacity to mount a political, economic, or even philosophical defense of the principles that launched the global democratic experiment.

On the other hand, many observers interpret the crisis of democracy as more perceptual than existential. Granted, when Foreign Affairs posed the question of democracy’s mortality to a slate of contributors this summer, several took a bleak view. The two lead essays, however, reminded us that democracy, especially its American iteration, has a historical track record of resilience in the face of great challenges, and suggested that the problems now besetting it at home and abroad can only overwhelm it should fear and apathy paralyze its guardians.

Despite these differences, most such musings on democracy amount to variations on a theme. Directly or implicitly, they suggest that the critical task is to protect – or perhaps resurrect – the so-called “liberal internationalist order”: the network of international institutions and alliances created after World War II, and anchored during the Cold War and post-Cold War years, by an American nation conceived as the model and best interpreter of democracy and its practice. The underlying assumption about that order, moreover, is that its true architect was not Franklin D. Roosevelt, but Woodrow Wilson, whose vision was rejected after World War I, but realized after another global catastrophe.

If the question, then, is whether the world order Wilson envisioned will survive, the unfortunate answer is no – for contrary to historical memory, it has never been brought into existence. Provided such an internationalist incarnation, however, democracy’s declining prestige and practice might indeed be arrested and reversed. Whereas the old, mislabeled “Wilsonianism” of the Cold War and post-Cold War decades has contributed to democratic morbidity in significant ways, a new and truer Wilsonianism can defend against pathogens without destroying the system or weakening its best defenses.

What Is Wilsonianism?

Debates over Wilson’s vision and legacy have long generated more heat than light. For decades, beginning in the 1960s, most discussion surrounded Wilson’s failures as a diplomatist and statesman. Was he a naive idealist or cynical imperialist? Both interpretations hold kernels of truth. Wilson won two elections promising to restore deliberative democratic processes, ensure justice for all participants, and achieve peaceful relations with other nations. When World War I imperiled the latter goal, Wilson cast intervention as a means to defend democracy, laying grounds for a League of Nations to promote political empowerment for all peoples. Yet under Wilson, Jim Crow advanced, U.S. interventions in Latin America increased, a humiliating settlement was forced on Germany, and countless imperialized souls saw their political futures entrusted to a League that was promptly abandoned by Wilson’s own United States. A generation later, stark injustices still plagued the United States, myopic nationalism hindered its responsible engagement in world affairs, and – as the League stood helpless – a second global conflict threatened democracy worldwide.

In the wake of the Cold War, a subtly different debate arose. This hearkened back to the aftermath of World War II and was premised on the assumption that, for good or ill, it was Roosevelt’s adaptation of Wilsonian principles that had defined the American-led struggle against authoritarian communism. Had the chimerically multilateralist-yet-unilateralist posture first assumed under FDR been vindicated by the fall of the Iron Curtain, or was it merely a pretense for equating the United States’ own interests with the good of humankind? Today, the argument is whether the old Wilsonianism of Roosevelt and his twentieth-century successors can survive our fractured informationscape, virulent sectarianism, and resurgent nationalism – and, of course, the exacerbating eruption of Donald Trump on the political scene.

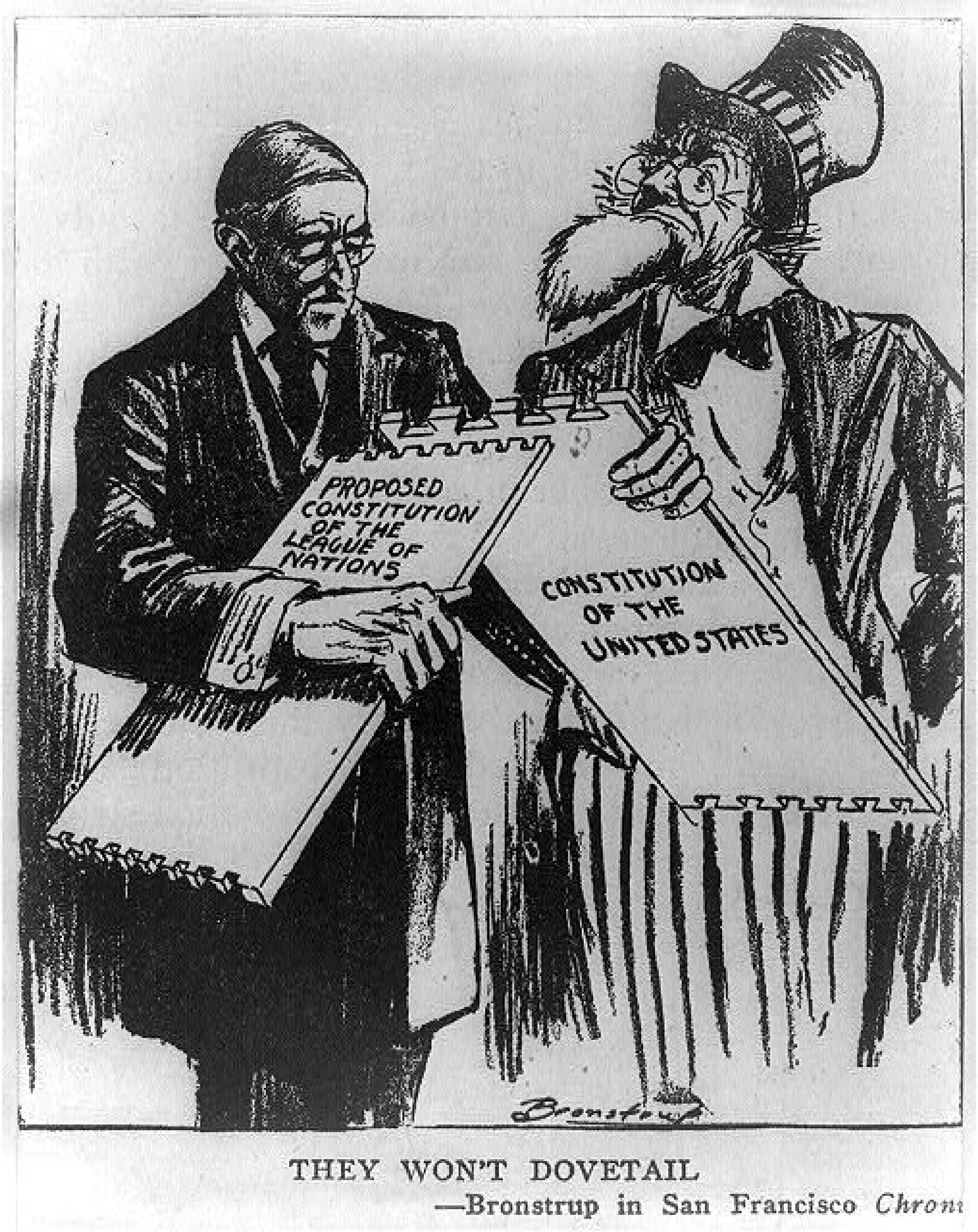

Reflected in such arguments is a drastic misunderstanding of the program central to Wilson’s vision: the League of Nations. Lost amid such arguments is how radical that vision was, and yet how practical. As noted, Wilson's foreign-policy record is far from perfect, and the same is true of the organization he asked his country to join. But the League – at least as Wilson designed it – had two advantages over the institutions founded by his World War II successors.

The first was real authority. Superficially, Wilson’s League resembled today’s United Nations in adopting a general rule of unanimity for its executive voting processes, effectively giving each of the great powers on its Council a veto over the world's majority will. Unlike Roosevelt, however, Wilson saw the veto, and unilateralism generally, as dangerous to international peace, and thus, to American security. And unlike the UN’s architects, Wilson inserted provisions in the League Covenant that prohibited parties to a dispute – including executive members like the United States – from participating in final votes on critical League decisions. The result was to lodge more authority and power in the community of states than in any one of its members, just as the U.S. Constitution elevates the federal government over individual states.

The second advantage proceeded from the first: legitimacy. Wilson knew that, even when great-power interests were not explicitly involved, the specter of great-power impunity would cast a pall over any ostensibly collective decision or action (especially in the view of the sanctioned or disappointed). He argued that both the League’s negative project of preventing war and its positive potential to promote prosperity, health, education, and justice across borders required affirming and institutionalizing the principle that “the rights of humanity are greater than the rights of sovereignty.”

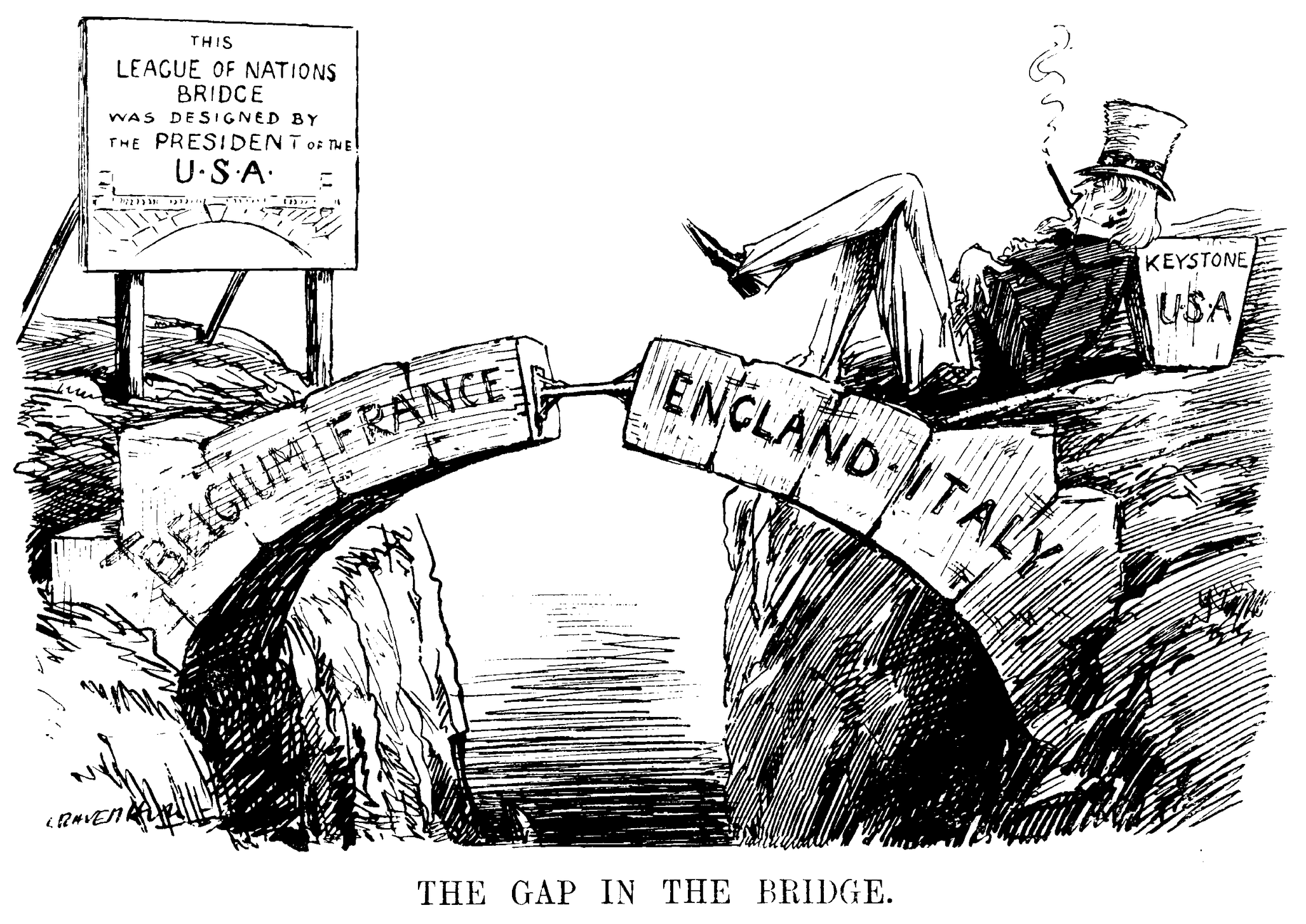

But didn’t the League fail? Yes – precisely because its Wilsonian incarnation was aborted in the Senate by nationalists happy to put sovereignty over practicality (and fairness). It is no exaggeration to state that U.S. abstention from membership crippled the League. And so, the practicality of Wilson’s design is solely demonstrable through the problems emerging from its destruction.

U.S. abstention meant the immediate obsolescence of the League’s economic boycott powers, due to fears America would simply scoop up any foregone trade with the boycotted. It also hampered any coherent international policy toward Germany. In short, American membership would have facilitated more coordinated responses to conflicts in the 1920s, better preparing the international community to tackle the apocalyptic crises of the 1930s – and perhaps preventing the worst from arising. Indeed, even if World War II were not averted, a record of constructive cooperation between America and Europe would still have made a difference to its legacy, providing plausible normative and institutional alternatives to the domineering model of global leadership America adopted after 1945.

Wilson’s great insight was that absolute sovereignty is a legal fiction and strategic delusion. “Every man who makes the choice to respect the rights of his neighbors deprives himself of absolute sovereignty,” he insisted. The alternative was anarchy of just the sort that had drawn the U.S. into the First World War, and would draw it into the Second. The United States, Wilson argued, would have to decide whether peace was worth accepting the chance that, like its fellow nations, it might occasionally “lose in court.”

The Un-Wilsonian Century

Wilson’s vision finds no parallel among any of his Oval Office successors. The familiar story of an American people wandering in an isolationist wilderness after World War I and finally emerging into the internationalist light after the Second is a fable. The great struggle since Wilson’s day has not been a binary contest between internationalism and isolationism, but a far messier competition among internationalism and various forms of unilateralism. Sadly – for America and the world – unilateralism has nearly always won.

True, Wilson’s program of international cooperation was stopped by Senate rivals who feared the nation’s entanglement in conflicts beyond its sole authority to address. Yet together with Wilson’s successors in office, these nationalists simply pursued their own strategy of international engagement: engagement without obligation. By actively promoting American economic and cultural influence worldwide, Republican administrations sought throughout the 1920s to knit the world into lucrative market networks without ensnaring the United States politically.

The crises of the 1930s and the coming of World War II revealed the deadly weakness of such a strategy. It also provided Franklin Roosevelt with a foil for a different strategic vision, one that came to dominate American diplomacy: globalism. Unlike their interwar predecessors, globalists embraced a hegemonic role for America in all aspects of international affairs – political and military as well as economic and cultural – justified by the principle that whatever advanced the interests of the world’s premier democracy would advance the interests of all peoples. Much like their predecessors, however, globalists assumed no obligations to other peoples – or rather, assumed obligations without accountability, defining and fulfilling them on American terms alone.

Neither the vision nor the reality of American foreign policy after 1945 has been Wilsonian in character or scope. Yet the number and diversity of policies to have acquired the “Wilsonian” sobriquet over the past 70 years is striking.

From the 1940s through the early 2000s, globalism reigned. Its principles were built into the League’s successor organization, the United Nations, with bipartisan support. Prominent “internationalist” powerbrokers like Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg made a veto over collective decisions the criterion of U.S. membership. Roosevelt himself came to favor the veto for permanent Security-Council members, anxious to preserve postwar control over the global deployment of U.S. forces. Roosevelt was also committed to great-power unanimity in international action, and thus, at least in the negatory sense, to great-power unilateralism – the antithesis of Wilson’s internationalism. Unfortunately, from the moment the UN Charter was ratified in 1945, its promising capacities in cultural diplomacy, world health, and disaster relief were undermined by the power politics it was ostensibly designed to constrain.

Perhaps the dynamics of the U.S.-Soviet relationship precluded another course. Regardless, neither the vision nor the reality of American foreign policy after 1945 has been Wilsonian in character or scope. Yet the number and diversity of policies to have acquired the “Wilsonian” sobriquet over the past 70 years is striking, including Truman’s globalization of communist containment; Eisenhower’s support of right-wing coups; Reagan’s impugning the UN; and George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq (and more in between). None involved or credibly advanced the multilateral resolution of disputes or cooperative pursuit of international goals. Each may share other features – good, bad, ugly – with several of Wilson’s policies, but to label them “Wilsonian” is to render the term applicable to every direct intervention by the United States in world affairs since 1776 – and thus meaningless.

In fact, American diplomacy since 1945 has been as un-Wilsonian as that of the 1920s and 1930s. Its overarching strategy for securing domestic safety and economic prosperity has been to subordinate international cooperation and organization to the pursuit of unrivalled power. That strategy has had several unfortunate effects: It encouraged Soviet counter-expansion and placed the burden of containing it on American shoulders. It propped up dictators, ballooned deficits, and stacked bodies from Guatemala to Vietnam. It sowed seeds of Islamist terrorism and armed rogue states with nuclear weapons, while eroding America’s moral authority to compel cooperation in maintaining global order. Its destructive legacy explains Obama’s earnest, if inconsistent, efforts to “lead from behind” – and his shrinking roster of achievements.

Calls to shore up the "liberal-internationalist order" ignore one discomfiting fact: that very order, at least in part, enabled the rise of Trump.

Yet surely, even specious Wilsonianism is preferable to full-blooded Trumpism, no? After all, under Trump and his Congressional enablers, America has destabilized the Middle East by sabotaging the six-power nuclear deal with Iran. It has legitimized murderous authoritarianism in Asia by conjuring a farcical nuclear deal with North Korea. It has wounded America’s closest economic allies in North America and Europe with its trade policies. It has undermined institutions, such as the Paris Climate Accords and UN Human Rights Council, which it could play a lead role in improving. And it has turned a legitimate concern over burden-sharing in NATO into a myopic campaign to malign its members and cast doubt on America’s commitment to a free and peaceful Europe – all while Putin’s Russia expands its malign influence.

All this reflects Trump's contempt for pluralism, for good-faith negotiation, for an ethic of mutual but proportional obligations and responsibilities, and for loyalty to fair processes over self-serving outcomes – in other words, for values central to the American constitutional system and critical to the functioning of any globally connected society.

But calls to shore up the "liberal-internationalist order" ignore one discomfiting fact: that very order, at least in part, enabled the rise of Trump. By refusing, for decades, to submit to any system in which the United States had to abide by collective decisions, policymakers opened the door for a leader with little if any regard for international norms and just as little appreciation of international interdependence. Worse, they fostered a culture in which national sovereignty is fetishized and American power equated, naively, with humanity's best interests.

As Trump has made clear, to "Make America Great Again" means to "go it alone" whenever Americans don't get their way, all the way, right away, because Americans are special and deserve to be treated as such. Having imbibed the same exceptionalist message over the decades as their president, it is no wonder many Americans think he is onto something.

Promises, Radical and Restorative

America is special, of course. It is the most durable example of a government and society in which even the largest centers of power are legally and institutionally constrained by their weaker counterparts. Indeed, it was America’s special example that guided Wilson in drafting the League Covenant. To Wilson, the notion that a powerful nation should be free to ignore or dictate to the world at large was as wrongheaded and dangerous as the notion that a powerful citizen should be exempt from, or superior to, the laws of his or her government. Sadly, too many of Wilson's successors embraced the first notion, setting the stage for a president who now explicitly promulgates the second.

The promise of a new Wilsonianism, then, is twofold. One is the radical promise of genuine internationalism. Geopolitics, economics, science, and medicine all tell us that the major threats and opportunities of our time are borderless – which is to say, mutual. Yet U.S. policy has never reliably supported genuine collective security, economic cooperation, or shared stewardship of the global commons. U.S. policymakers have never accepted any system in which they might actually “lose in court,” and only rarely have they submitted U.S. perspectives, plans, and prejudices to the scrutiny that even a crudely scientific (let alone democratic) ethos would demand. In that sense, we do not need a new Wilsonianism in foreign affairs. We just need Wilsonianism, properly understood.

The second promise is the restorative promise of civic nationalism. The scientific-democratic habits that U.S. policymakers often fail to practice internationally are the same that U.S. citizens and their representatives increasingly fail to practice domestically. They are, in the words of William James, the habits of “civic courage” through which truly great nations are made – and saved – “day by day”:

… by speaking, writing, voting reasonably; by smiting corruption swiftly; by good temper between parties; by the people knowing true men when they see them, and preferring them as leaders to rabid partisans or empty quacks.

As James’s own gendered language suggests, few people, at any time or place, have found it easy to practice these virtues with the self-scrutiny and self-awareness they demand. Nor did Wilson supply a perfect model of civic courage. Instead, he supplied a regulative ideal, and a framework for realizing it – not immediately, not perfectly, but day by day, with the humility that brings wisdom and the prudence that underwrites boldness.

It is in that spirit – rejecting tales of golden ages as well as prophecies of doom, and knowing that our complicated past cannot provide solutions, but can suggest directions – that Americans should imagine their role in human affairs. That is the spirit of a world-leading people – whatever the name we use to conjure it.

***

Trygve Throntveit (@throntv) is dean’s fellow for civic studies at the University of Minnesota’s College of Education and Human Development. Formerly a lecturer and the assistant director of undergraduate studies in the Department of History at Harvard University, he is the author of Power without Victory: Woodrow Wilson and the American Internationalist Experiment.

Cover photo: A banner-size painting of Woodrow Wilson hangs from a building, circa 1920. The caption partially reads: "Originated to portray the bigness of the man whose heart is bigger than the portrait." (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)