A refugee looks back: What the 1940s teach us about today’s crisis

– Milan J. Kubic

In the late 1940s, an intransigent Congress made it difficult for many post-WWII European refugees to come to the U.S. Among those displaced persons was Milan J. Kubic, the author of this piece. This is how President Truman fought Congress, won, and opened America's doors.

European officials who are at loss for what to do with the Middle Eastern and African refugees pouring into Germany and Austria should recall Ecclesiastes 1:9: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” Startling as it has been, the tidal wave of desperate and impoverished asylum-seekers who have been arriving in Western Europe is far from unprecedented. Millions of similar victims of violence who were made homeless by World War II paid the same compliment to the free part of the Old World in the 1940s and early 1950s.

Yet within a decade after World War II ended, this great humanitarian upheaval was over, the old continent was rapidly recovering from the catastrophe, and the great majority of the refugees were repatriated or resettled — myself included. The solution to the humanitarian crisis was a historic achievement that is largely attributable to President Harry S. Truman.

While war still raged in Europe and the Pacific, America got ready to help the displaced persons (or DPs, as they came to be known). In November 1943, at President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s invitation, representatives of 44 nations met at the White House and established the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), an international agency to plan and coordinate “measures for the relief of victims of war.”

By the time the war ended in 1945, there were an estimated 20 million DPs roaming the European continent. They were a chaotic mix: Jewish survivors of concentration camps; German civilians fleeing their destroyed cities; freed Soviet Red Army prisoners of war; remnants of Ukrainian, Italian, and Hungarian troops who had fought alongside the Wehrmacht; and the countless slave laborers that the Nazis had rounded up in occupied countries and forced to work in armament factories and on huge fortifications along the French coast.

UNRRA was overwhelmed by the deluge of destitute refugees left behind by the advancing Allied armies and the collapsing German Wehrmacht. Though it had distributed $3.7 billion worth of clothing, food, medicine, and tools to the homeless victims of the war, the young organization was not well suited for the scale of need. From 1947 on, care for the DPs was turned over to the International Refugee Organization (IRO), a United Nations agency that was better financed and organized for the task, which grew to a monstrous size.

In the years after the war ended in Europe, UNRRA and IRO helped repatriate about 11 million uprooted people. Millions of refugees managed to return to their homes on their own. Others had no home — at least none that they could return to.

More than 600,000 liberated Jews were brought (legally and illegally) to Palestine by Zionist organizations, where in time they helped establish the state of Israel. Another 250,000 displaced Jews did not wish to go to Palestine. In 1945, they and roughly 600,000 other DPs — mostly Poles and other eastern Europeans who refused to return to their home countries, which had come under communist rule — lived in camps scattered throughout the U.S., British, and French occupation zones in Germany and Austria.

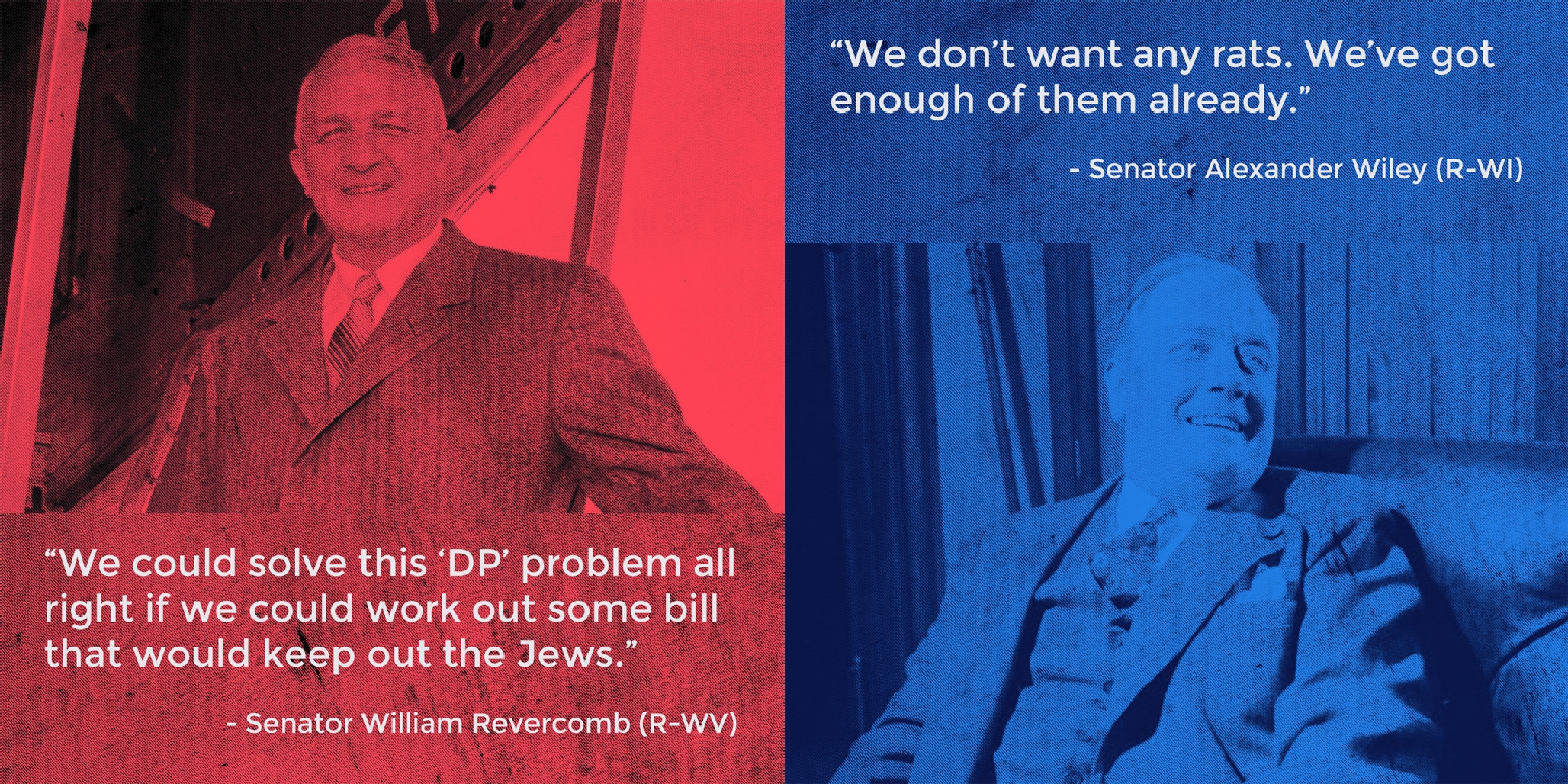

The great majority of these “non-repatriables” wanted to emigrate to the United States. In that, they faced a formidable obstacle: the U.S. Congress, which was dominated by arch-conservatives who considered Jews and Slavs a threat to the Anglo-Saxon character of the United States. “We could solve this ‘DP’ problem all right if we could work out some bill that would keep out the Jews,” Senator William Revercomb of West Virginia told his colleagues in 1948. Senator Alexander Wiley, the Wisconsin Republican who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee, took a similar position, calling on the United States to admit only those people with “good blood”: “We don’t want any rats. We’ve got enough of them already.”

Asked to enact “adequate and decent laws” to let refugees in, the 80th U.S. Congress instead produced a bill designed to do the opposite. President Truman would declare the proposal unacceptable, denouncing it as “anti-Semitic” and “anti-Catholic.” It was an early salvo of a political battle that the combative president launched against what he called the “do-nothing” 80th Congress, and would become an issue of Truman’s 1948 reelection campaign.

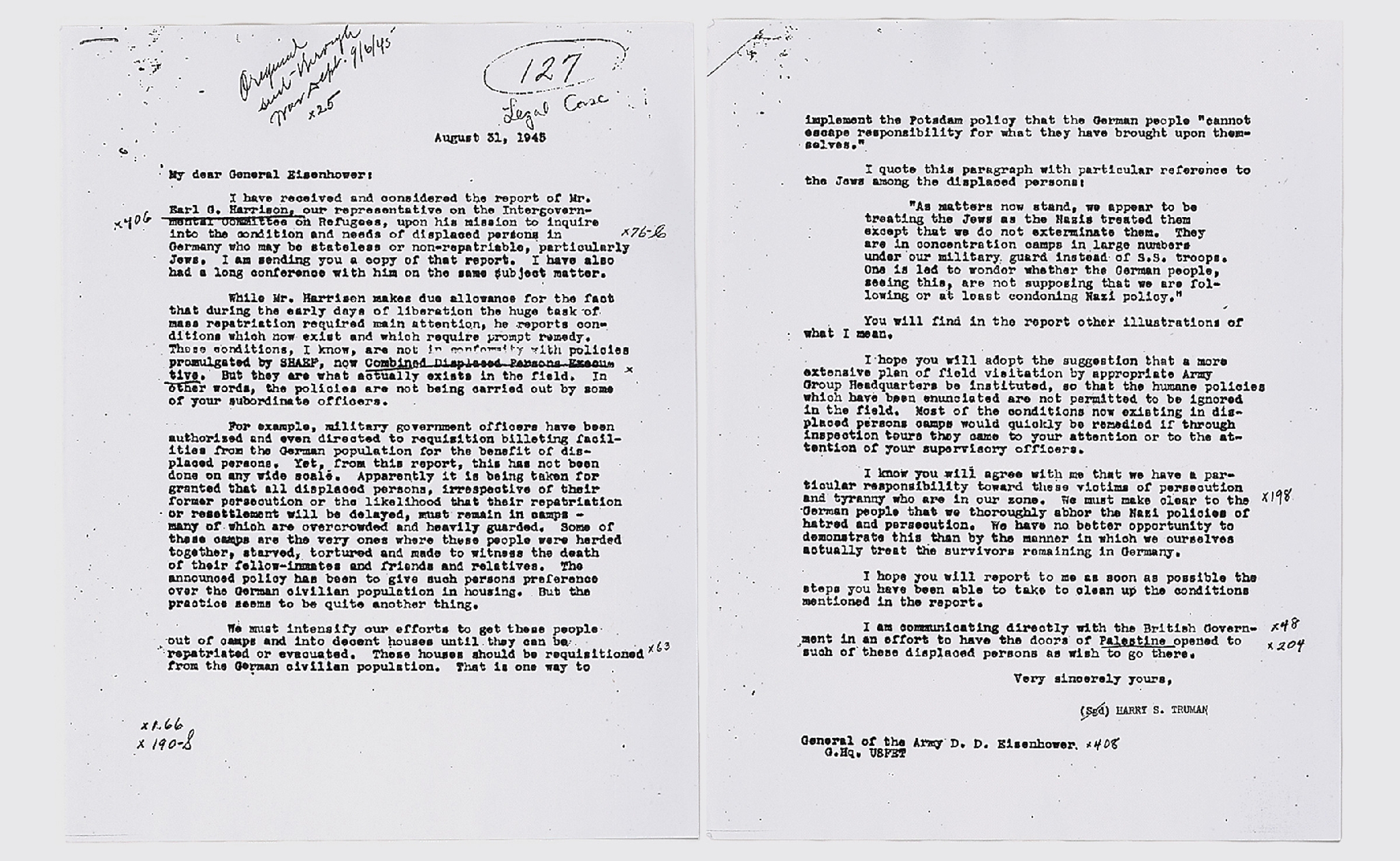

President Truman began preparing for the showdown in 1945, just two months after taking office. His first step was to ask Earl G. Harrison, the dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, to investigate the conditions of the DPs and help design “plans ... to meet their needs.” Harrison left for Europe in June, and a month later delivered Truman the data he needed.

Harrison found that the “non-repatriables” were living in wooden barracks that the Nazi regime had built for the slave laborers and prisoners of war. “One must raise the question as to how much longer many of these people, particularly those who have over such a long period felt persecution and near starvation, can survive on a diet composed principally of bread and coffee,” Harrison reported. “In many camps, the 2,000 calories [in refugees’ diets] included 1,250 calories of a black, wet and extremely unappetizing bread.” The DPs were demoralized and lacked medicine, clothing, and fuel for the coming winter. “UNRRA,” in Harrison’s opinion, “being neither sufficiently organized or equipped ... has not been in position to make any substantial contribution to the situation.”

President Truman promptly wrote to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commander of the Allied armies in Europe, and asked him to do what he could to improve the conditions in the camps. On December 23, 1945, two days before the first postwar Christmas, the president directed U.S. consulates worldwide to give preference to DPs when filling U.S. immigration quotas. The directive, which specified that the “visas should be distributed fairly among persons of all faiths, creeds, and nationalities,” brought to America 40,000 refugees that Congress tried to keep out.

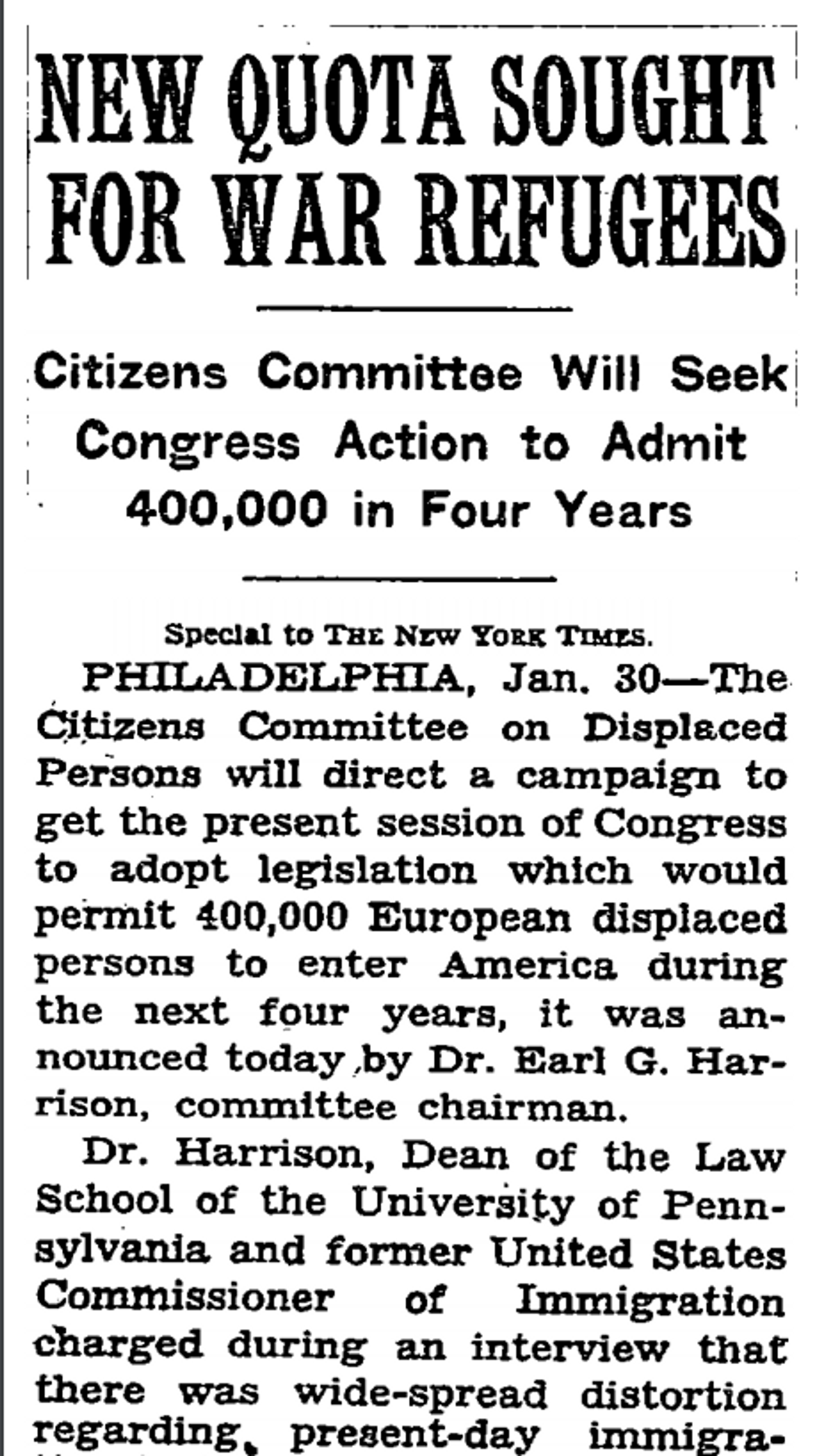

Even with Truman’s fairness directive, immigration quotas still effectively prevented most refugees from entering the United States; to admit more of them, the law needed to be changed. To generate public pressure behind his campaign, Truman asked his liberal allies to join the Citizens Committee on Displaced Persons, a nonsectarian organization founded in 1946. The group — which was chaired by Harrison and included such prominent Americans as Eleanor Roosevelt, labor leader David Dubinsky, department store owner and Chicago Sun publisher Marshall Field III, and civil rights organizer A. Philip Randolph — lobbied for a temporary suspension of restrictive U.S. immigration quotas.

To keep the issue high on the country’s conscience and agenda, Truman unleashed what his biographer, David McCullough, would later describe as the president’s favorite strategy: “attack, attack, attack.” In his 1947 State of the Union Message, Truman informed Congress that he did not “feel that the United States had done its part in the admission of displaced persons,” and called for new immigration bill. Six months later, he sent the legislators a special message reminding them that “we are dealing with a human problem, a world tragedy,” and urging Congress “to pass suitable legislation as speedily as possible.” When Congress adjourned without responding, Truman returned to the subject in another address to Congress in January 1948. In the course of the year, with his reelection campaign in full swing, he denounced the congressional bigotry in rallies from coast to coast.

The duel culminated on June 25, 1948, when Congress, on the last day of its session before recess, presented Truman with an immigration bill that he again considered grossly inadequate. The president responded with one of his most furious salvos against his political opponents. He called the bill “flagrantly discriminatory,” and said that he had signed it “with very great reluctance” and only because otherwise “there would be no legislation on behalf of displaced persons until the next session of the Congress. “It was “a close question,” he said, whether the measure was “better or worse than no bill at all.” He went on to acknowledge the proposal’s “good points” — mainly, the recognition of “the principle … that displaced persons should be admitted to the United States,” and a provision for the admission of 200,000 displaced persons, 3,000 orphans, and 2,000 refugees who had fled after the communist coup d’état in Czechoslovakia.

But “the bad points,” Truman thundered in his June 1948 statement, “are numerous [and they] ... form a pattern of discrimination and intolerance wholly inconsistent with the American sense of justice.” Specifically, he charged that “the bill discriminates in callous fashion against displaced persons of the Jewish faith” by “exclud[ing] Jewish displaced persons, rather than accepting a fair proportion of them along with other faiths.” Further, the bill “excludes many displaced persons of the Catholic faith who deserve admission,” and “contains many restrictive requirements, such as prior assurances of suitable employment and ‘safe and sanitary housing,’ unnecessarily complicated investigation of each applicant, and burdensome reports from individual immigrants.” Drawing to a close, Truman expressed regret “that the Congress saw fit to impose such niggardly conditions,” and put lawmakers on notice that he had signed the bill with the expectation that Congress would take the necessary remedial actions when it reconvened.

That November, Truman, against all expectations, won a victory that not only kept him in office but also put the Democrats in charge of both the House and the Senate. The astonishing victory in part reflected voters’ growing recognition that Truman was right on the immigration issue. One of the convinced Americans was Truman’s general election opponent, Republican New York governor Thomas E. Dewey, who less than a month after the Republican Congress had passed its Displaced Persons Act expressed some reservations about it and called for a “liberalized DP law.”

For all its faults, the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 marked the beginning of the end of the non-repatriables’ odyssey. Even before the law was passed, UNRRA and IRO had begun grouping us by nationality and moving us from the drafty shacks to more solid quarters. The transfers, which took place while Europe was still mired in chaos and suffered severe food shortages, did not ease our hunger and discomfort. Winter clothing for the refugees was made so small that I, at five-foot-ten and 125 pounds, could not get into the pants. In 1949, the mess sergeant in our large IRO camp in Ludwigsburg, in southern Germany, reported that one-third of the 2,000-calorie daily rations he was slated to receive for the DPs had been stolen before reaching his kitchen. For many of us, finding Americans to sponsor our emigration to the United States presented a hurdle that, just as Truman predicted, was hard to clear.

But the availability of more than 200,000 U.S. visas encouraged American religious and civic relief organizations to open offices in the DP camps and step up their efforts to help the refugees. In a surprisingly short time, we would be called to new processing centers for interviews. By the fall of 1948, refugees who qualified under the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 began boarding U.S. Army transport ships that had brought GIs to Europe to man the new NATO bases.

The first 813 of these refugees left the German port of Bremenhaven on October 21, 1948. The trip to New York was free, the food on board was ample, and the American Red Cross gave each immigrant a welcome-to-the-U.S. gift of six dollars.

My own crossing aboard the USAT General A. W. Greeley was in keeping with the rest of my DP experience. We left in the middle of February 1950, and the sea was so rough that the ship’s propeller spent seemingly one-third of its time out of the water, winds pushed the ship off course, and the normally week-long crossing took 18 days. Since we had no drugs against sea sickness, most of us ate little or nothing until we reached terra firma. Otherwise, except for a glancing collision with another army transport in the foggy English Channel, the trip was uneventful.

When I was not too seasick, I worked behind the counter of the ship’s commissary, or PX, and helped put out the souvenir edition of the ship’s journal. It may be of some historic interest that the six-dollar gift each refugee received from the Red Cross translated into about 120 candy bars, Cokes, or packs of chewing gum. In the PX, the bestsellers were Hershey bars, Oh Henry! bars, V8 juice, Coca-Cola, and — wonder of wonders — nylon stockings for women. Every time the crazy sea calmed down enough for the PX to open, the store was mobbed by eager customers. By the time we pulled into the New York harbor on the freezing cold morning of March 3, 1950, the commissary’s wares were practically all sold out.

On July 16, 1950, the 81st Congress passed an amendment of 1948 Displaced Persons Act which, the president said, he signed “with very great pleasure.” The new law authorized a total of 400,744 visas, more than 172,000 of which had been already issued.

With hundreds of refugee-filled U.S. Army transports crossing the Atlantic, the DP camps rapidly emptied, and the last “non-repatriable” displaced persons — a former Polish slave laborer, his wife, and their two children — arrived at New York’s Pier 61 on Sunday, April 13, 1952.

Including the additional immigration authorized in 1953, the United States admitted a total of 600,000-plus World War II displaced persons and refugees whose homes were behind the Iron Curtain. An additional 400,000-plus displaced persons were resettled by Great Britain, Australia, Canada, and other Western countries. By the end of 1955, Europe’s World War II migration crisis was over.

In his memoir, Years of Trial and Hope, President Harry S. Truman wrote, “All my life, I have fought against prejudice and intolerance.” The fight may have to be waged and won again to resolve the plight of the Middle Eastern migrants in Europe.

* * *

Milan J. Kubic was a correspondent for Newsweek magazine from 1958 to 1989. Born in Czechoslovakia, Milan was a refugee and lived in displaced persons camps in the U.S. zone in West Germany from June 1948 to February 1950.

Cover photos courtesy of das Bundesarchiv and Rebecca Harms