Winter 2020

Protest and the Muse

– Richard Byrne

The Velvet Revolution and an American graduate student inspired Bohumil Hrabal -- one of Central Europe's greatest writers -- to create a classic work on the collision of politics and art.

“So there I stood in front of the pub in my Russian fur hat, while all the people who had been in Wenceslas Square streamed past me, shouting and carrying placards…. I’d never seen so many beautiful unblinking people, I’d never seen such solemnity in young people… I walked along with them and I came to my old Law Faculty, where across the bridge the white helmets gleamed and shone – and I stood where 50 years ago I saw the Army and SS-Waffe hounding my fellow students out of the Faculty… (Bohumil Hrabal, “November Hurricane,” 21 November 1989)

The Velvet Revolution in 1989 was Czechoslovakia’s fifth political convulsion of the 20th Century. All of these events shaped the career of Bohumil Hrabal – one of the greatest Central European writers of his era.

He was born in 1914, just a few months before Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot dead in Sarajevo, and only four years old when Czechoslovakia was born after the First World War. He was a 24-year-old studying law when the Germans marched into Prague in 1939.

Hrabal took his law degree in 1946, but never practiced. As the Communists seized power in 1948, he began to write the literary works that would bring him fame. By the time of the Prague Spring in 1968, he was one of Czech literature’s brightest stars – an ascent confirmed by the Best Foreign Film Oscar in 1968 awarded to the adaptation of his novella, Closely Watched Trains. (Hrabal co-wrote the film’s screenplay with director Jiří Menzel.)

During the dark period of so-called “normalization” that held sway in the 1970s and 1980s, after the Russian invasion, Hrabal did not emigrate. He did not sign the classic protest manifestos of that era, such as Charter 77, as many writers did. Instead, he bobbed and weaved with authorities (and with himself) in those years, facing bans and harassment.

When he did get permission to publish, Hrabal’s works and interviews often were censored or mutilated. Yet new masterpieces also flowed from his typewriter into samizdat editions, much to the fury of Czechoslovak Communist authorities.

The Velvet Revolution of 1989 was the final political switchback of Hrabal’s long life. The 75-year-old writer shared a final burst of literary greatness in response. In a stylistically-complex and shatteringly-candid series of “collage” essays, known as Letters to April (Dopisy Dubence), Hrabal grappled with his intensely conflicted emotions about revolution, politics, and art – and his own fraught and fearful relationship with totalitarianism.

Hrabal wrote that his Letters to April was, in part, “a confession about my fear.” They also were written as he grieved over the recent death of his beloved wife, Eliška “Pipsi” Plevová.

Yet Letters to April is also the work of writer suddenly energized by renewed hope in his art and his life. A new muse had stirred the writer’s creativity.

The Velvet Revolution of 1989 was the final political switchback of Hrabal’s long life.

Aleksander Kaczorowski, author of the 2016 biography, Hrabal: A Sweet Apocalypse, says that the Letters to April “are extremely interesting, not only as a testimony of the era of post-communism in Central Europe, or as a source of knowledge about Hrabal himself, but also as an artistic achievement.”

Hrabal’s version of his friendship with a young American woman named April Gifford is contained in Letters to April. But what about April? She has told her story rarely in the Czech Republic. She has not spoken about it with an American journalist.

Until now.

A Young Woman with a Five-Kilo Dictionary

Even today, 30 years after Communism’s collapse, the traditional Czech pivnice (or beer hall) can be a dauntingly masculine preserve. In 1987, a renowned Prague pub like U Zlateho Tygra (or “At The Golden Tiger”) was very much a boy’s club.

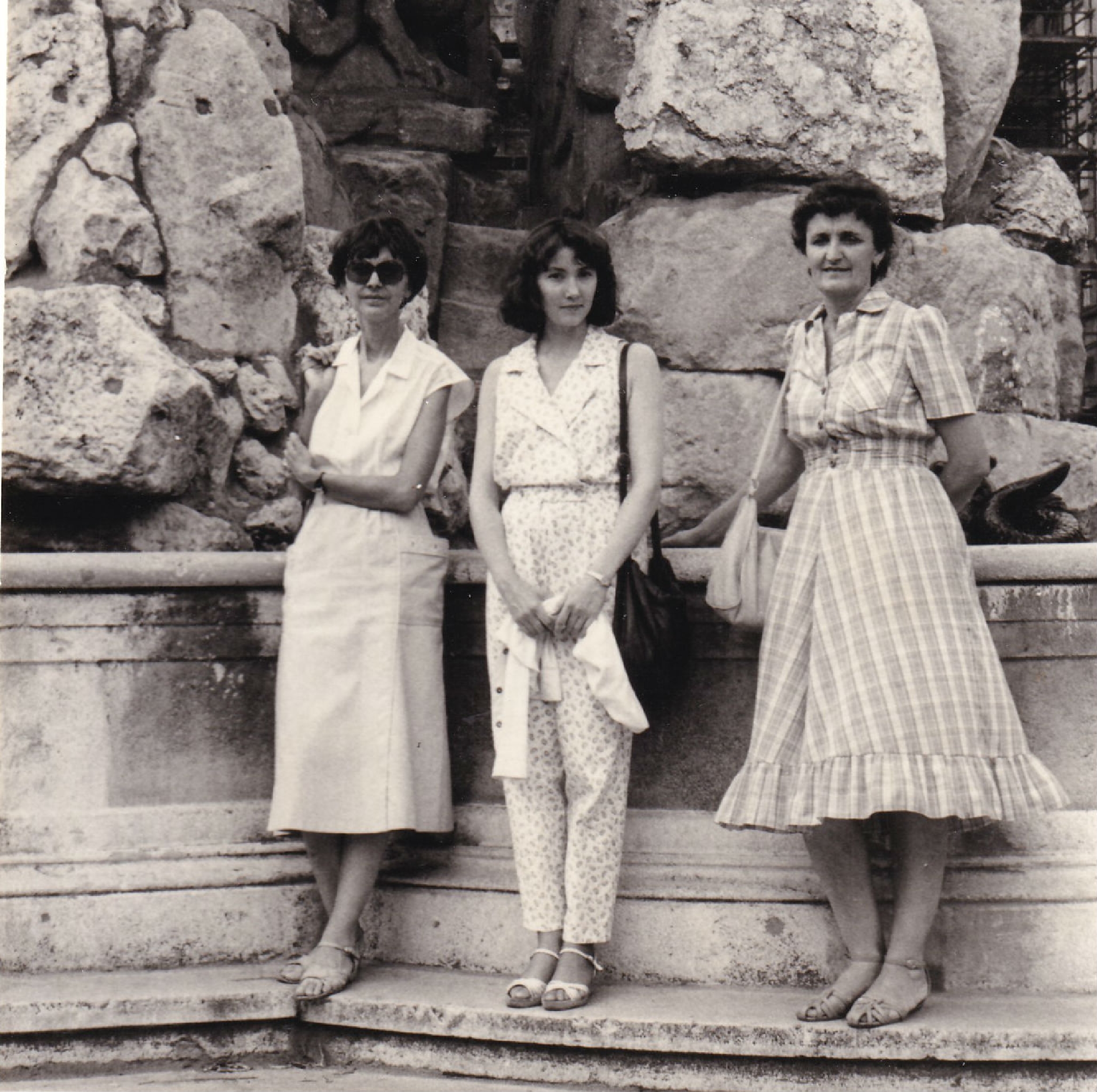

Yet Stanford University graduate student April Gifford, recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship, proved undaunted. While Prague in the 1980s could be dank, repressed, and polluted, she found it irresistible.

“My whole being opened to the beauty of Prague,” she says, “even as I knew about its current repressiveness.”

Though she had read some of Hrabal’s writing at Stanford, Gifford was impressed greatly by the overwhelming laughter she witnessed at stage adaptations of his prose. “There were so many people in the audience, laughing so hard…. the audience engagement was amazing.”

Gifford wanted to write about Hrabal – and the unexpected laughter his work elicited in a country that PEN International dubbed “the Sleeping Beauty” – for International Herald Tribune. “Even though I'm not a journalist,” she reasoned, “maybe since I'm here in Czechoslovakia, and this is going on, they'll sit up and pay attention.”

Czech friends advised her to seek out Hrabal at his favorite haunt: U Zlateho Tygra. He was the most influential writer of a generation that included novelist Milan Kundera and playwright Vaclav Havel – a prominent political dissident who later became president of both Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic.

The works of Bohumil Hrabal resist easy distillation, but they find their power in two Czech artistic traditions: the ribald palavering of pubs (immortalized by Jaroslav Hašek in his 1922 novel, The Good Soldier Švejk), and a modernism created by artists in the 1920s including poet Jaroslav Seifert and writer Karel Čapek (who coined the word “robot”), and informed by the international currents of Cubism, Surrealism and Dada.

“My whole being opened to the beauty of Prague, even as I knew about its current repressiveness.”

Hrabal was a relentless literary innovator. His Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age is a novella written in a single breathless sentence. Yet his work is steeped in foaming lager beer and smoky air of Czech pubs. It is writing that renders uncommon depths with a common – and comic – touch.

Hrabal’s regular table was in the back of U Zlateho Tygra, where a large pair of antlers hung on the wall. With some patience, and endurance of gentle hazing from Hrabal’s friends, she finally met the writer.

Gifford always dragged a large Czech/English dictionary around with her in those days, eager to soak in as much as Czech as she could. “The reason I carried it with me was that I took language study so seriously,” she says.

But it was Gifford’s good nature and humor –and not her dictionary – that won Hrabal and his friends over. One of them dubbed her “Dubenka,” after the Czech word for “April.” The endearment stuck.

Hrabal recalled his early impressions of Gifford in “Public Suicide,” the first of his Letters to April:

Dear Dubenka, during your first visit to Prague, you said things in Czech that drove us wild…. Folks, I went to see Mandlíková play tennis, and d’you know what she said when she flunked the ball?… To jsem posrala!— I buggered up! Is it OK for me to say that? So Mr Marysko said… Lassie, we say that all the time – and where did you hear it? And you innocently said… In San Francisco.

Gifford says she delighted in playing to the table under the antlers at the pub.

“I had friends,” she recalls, “who loved teaching me words and phrases that a woman with my background would not normally say. These friends taught me these phrases to try out on Mr. Hrabal.” Eventually, she adds, “Mr. Hrabal's friends would actually egg me on more than he did. But he would laugh, and he was listening to me.”

Gifford recalls being especially impressed by Hrabal’s voice. “The stress in Czech is always on the first syllable, and that gives it a certain musicality. But the way Mr. Hrabal spoke and read was especially musical. It was very mellifluous. When he read, it was beautiful and people noticed. I can still hear it to this day, you know. A fantastic voice.”

Gifford meditates to this day upon what she calls the “asymmetry” between the privilege of her American world and the Czechoslovakia in which she found herself immersed in 1987: “Who can help where we are born, and what we are born into? And who was I to meet such a renowned author?”

Gifford and Hrabal’s friendship deepened. Not only was she welcome at U Zlateho Tygra, but she was invited to the writer’s chalet in Kersko, in the woods northeast of Prague. But the whirlwind adventure of writer and graduate student ended when Gifford’s fellowship concluded. She headed back to Stanford to finish her dissertation.

To The Delighted States of America

Among the most enchanting bits of wordplay in Letters to April is Hrabal’s transmutation of the United States (“Spojené státy americké”) into the “Delighted States” (“Spokojene staty”) Gifford recalls making this linguistic slip at the Tiger, and Hrabal affectionately claimed it for his own work.

And as the writer was California dreaming in Prague, Gifford had a brainstorm in Palo Alto: A U.S. reading tour for Hrabal in early 1989.

The logistics of any such tour are difficult to arrange. That Czechoslovakia was still under communist rule made it much more difficult still. Perhaps improbable. Would Hrabal be given a visa? Would the writer be allowed to leave the country?

Gifford’s sheer tenacity made the Hrabal tour happen. She dealt with the Czechoslovak embassy, arranged talks for the author, and worried every detail of a transcontinental journey. She created a nonprofit student organization at Stanford to help manage the finances. The first check for the tour came from two-time Oscar winning Czech director Miloš Forman. Many other emigres, foundations, and organizations followed his lead.

Hrabal’s U.S. publisher arranged for Swiss literary critic and translator Susanna Roth to accompany him on the trip. But the tour had a rocky start, even before Hrabal got on the plane. His anxieties about his visa and travel arrangements were so intense that he took a hard fall after a bout of drinking in Prague before the flight.

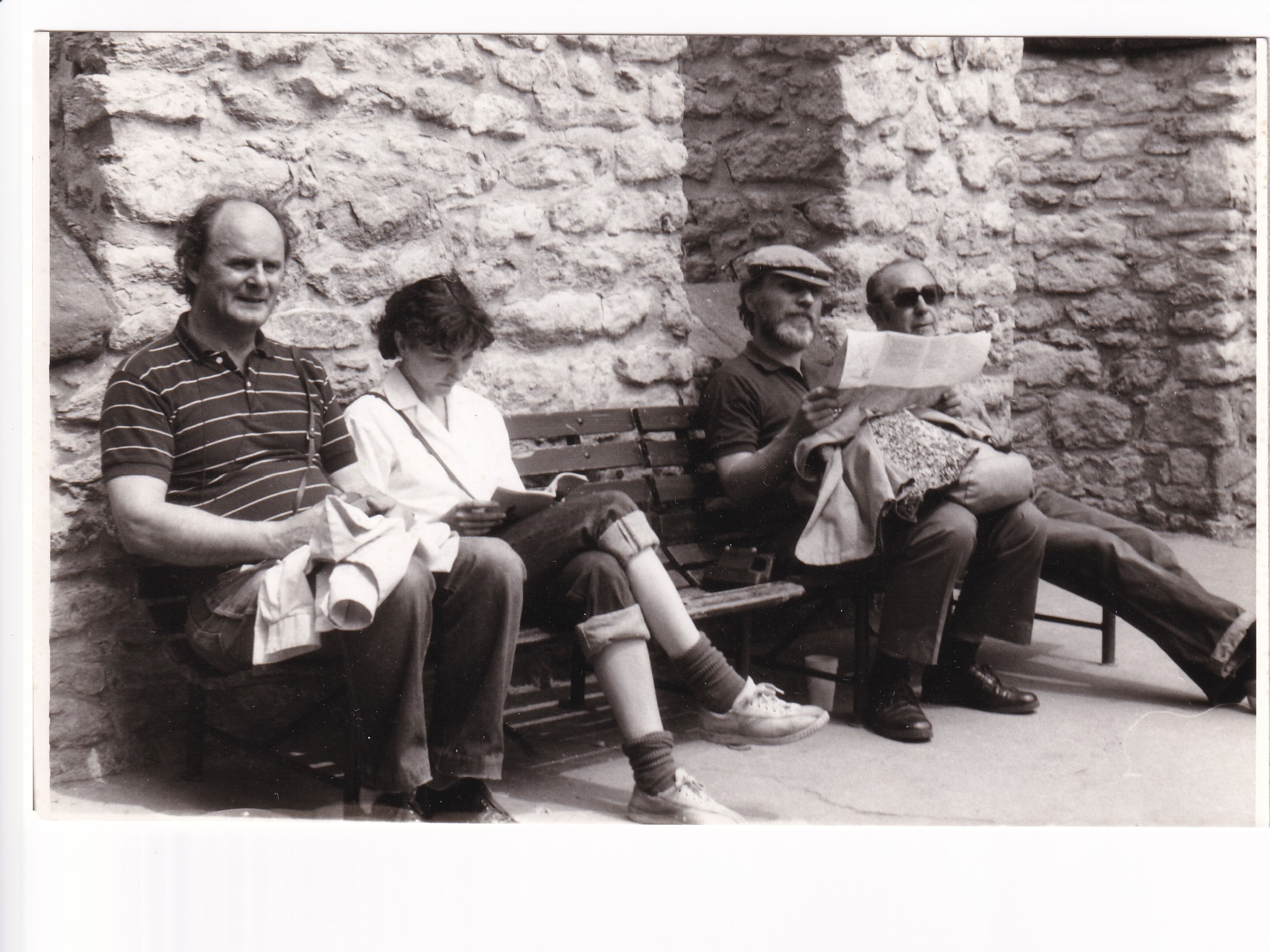

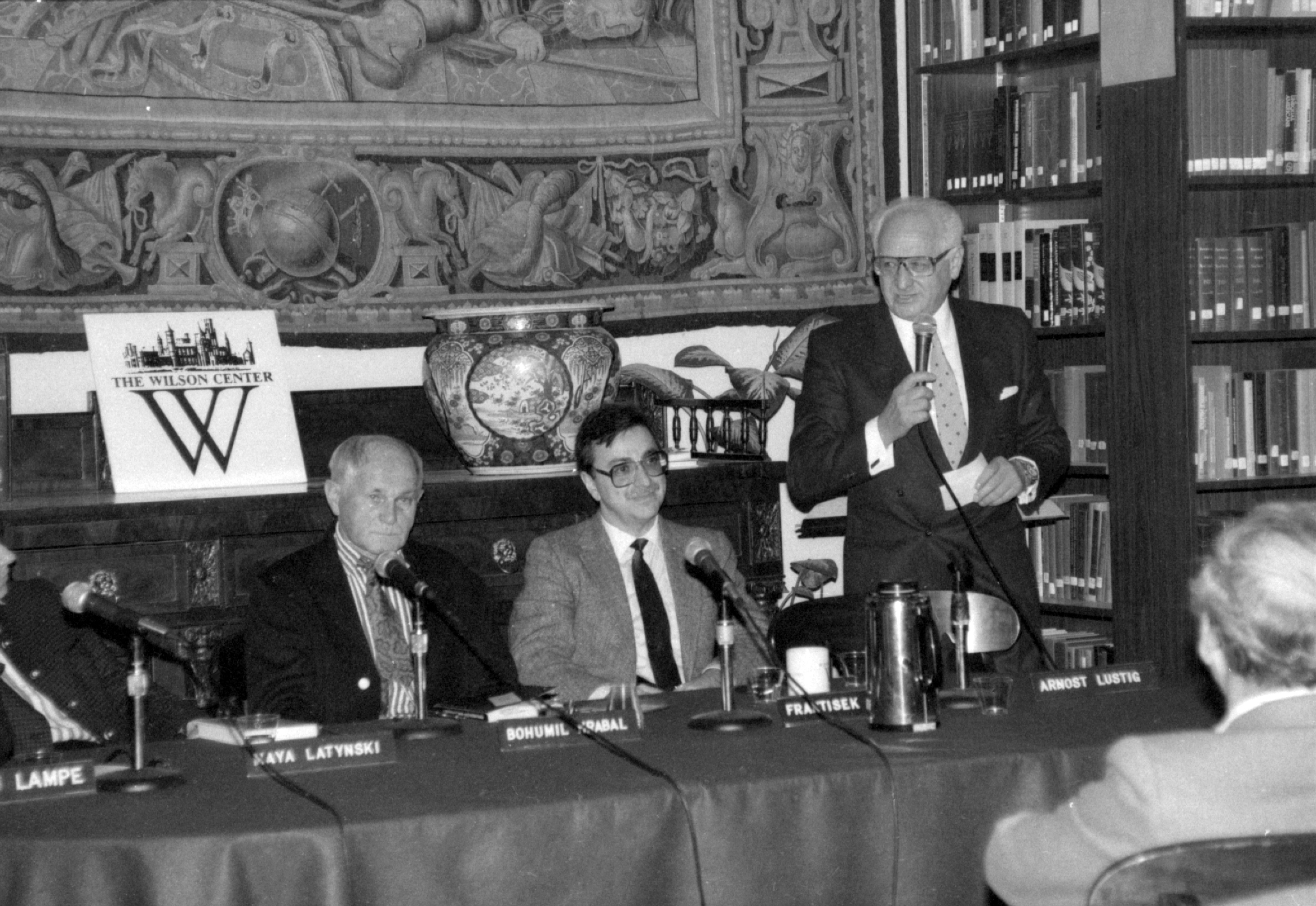

Hrabal was still a bit worse for wear at his first U.S. appearance – a panel held on March 22, 1989 at the Woodrow Wilson Center – where was introduced by Czech novelist Arnošt Lustig.

The tour continued in New York, where Hrabal played “literary ping pong” with writer Susan Sontag. “[S]he said Philip Roth…,” he writes, “and I said Joseph Roth, The Capuchin Crypt.”

The writer’s trip swung west to Chicago, Nebraska, and other stops, and then on to California. In Letters to April, the literary ping pong continues apace. Hrabal muses on Dylan Thomas in New York, on poet Carl Sandberg, and on Beat Generation writer Jack Kerouac, who made similar far flung journeys across the American landscape in On the Road.

Gifford’s sheer tenacity made the Hrabal tour happen. She dealt with the Czechoslovak embassy, arranged talks for the author, and worried every detail of a transcontinental journey.

In Letters to April, Hrabal invokes Greek mythology to describe the tour – and Gifford’s role in organizing it. “You’re Ariadne, and I’m Theseus, you’re unwinding a several-thousand-kilometre-long thread…” And the thread led at last to Stanford University, and a final reading on the tour on April 25, 1989.

Gifford gave a brief – and slightly nervous – introduction. Then Hrabal read and spoke, with simultaneous translations provided by Michael Henry Heim – a UCLA professor who placed some of Hrabal’s greatest works (including Too Loud a Solitude and The Death of Mister Baltisberger) before English-speaking readers.

Hrabal and Gifford parted again when the tour was over. She finished her thesis in 1993, but not before suffering the setback of a major depression. She eventually left her field. Gifford started a family in the U.S., and did not return to Prague until long after the writer’s death in 1997.

Conquering Fears

Though their paths in life had diverged, the literary story of Hrabal and April wasn’t over.

Hrabal began to write Letters to April after the U.S. tour. But as early as January 1989, he already was exploring epistolary forms that juxtaposed personal reflections, literary allusions, and political observations. One such piece, written before the tour, was “Kouzelná flétna” (“Magic Flute”), which anticipates many events of that auspicious year.

Yet it was the rapid deterioration and collapse of the Czech communism that spurred Hrabal to write an entire series of collage-like epistles addressed to Gifford, beginning in August 1989 and into 1990.

Letters to April is an exquisite literary trapeze act, leaping to connect past and present, personal and public. In one letter, titled “Meshuge Stunde,” Hrabal vaults nimbly from Bulgarians dressing up statues of Josef Stalin (“so that Stalin wouldn’t catch cold”) to the famed Infant of Prague (a wax Baby Jesus doll dressed in a new clothes every day by nuns in a church in the city’s Mala Strana quarter), and lands at last upon the makers of the Velvet Revolution, whom he calls:

Millions of little Jesuses, dressed up as students, actors, clowns, and young people, who gave precedence over strict knowledge to the inclinations of their heart…

Aleksander Kaczorowski says: “I think that the visit to America and the Velvet Revolution extended the life of Hrabal by several years. They certainly stimulated his creative inspiration; it was thanks to these events that he was active as a writer until the mid-1990s.”

Hrabal never mailed his “letters” to Gifford. He did publish them quickly, however. The first volume – titled November Hurricane (Listopadový uragán) – appeared in early 1990.

There was a touch of the urgency of a broadside about it. Documentary footage from the era – in a film produced by the Archiv Českého Exilového Umění (Archive of Czech Exile Art) in 2015 and titled Na přelomu časů (below) – shows booksellers unwrapping copies of November Hurricane and selling them on the street in the center of Prague as Hrabal watches and signs copies of his latest work.

Eventually, these published copies of the letters also reached their addressee.

“I was in shock,” Gifford recalls. “Because I’m very private…. But I understood that he meant it as a gift, and that coming from him, it was an honor.”

Letters to April also documents Hrabal’s studied ambivalence about politics in literature. He was more active in opposition than is generally acknowledged during the Prague Spring, and was quickly banned from publication by ascendant hardliners after the Soviet tanks rolled in.

Yet Hrabal never signed the great documents of Czechoslovak political opposition to communism after 1968. The writer was allowed to publish and collaborate on films again after the publication of an interview in the journal Tvorba in 1975 – a conversation altered substantively by editor, and augmented with pro-regime passages not uttered by Hrabal himself.

Controversies over Hrabal's muddy politics during the 1970s were complicated further by his role as a continually vexing figure to the same authorities who once had pulped his works and forbade their publication. Some of his best prose writings of the 1970s and 1980s were smuggled out of Czechoslovakia and published (uncensored) in samizdat editions.

Aleksander Kaczorowski observes that Hrabal “hated the ideological, political boxing he had experienced all his life, not just from the communists. In fact, he recognized only aesthetic criteria; only beauty justifies the world, the existence of man, the existence of a writer. And everyone can do beauty, even the guys sitting at the beer hall.”

Yet politics often intruded in assessments of his work and character. In “November Hurricane,” Hrabal recalls a question and answer session on his U.S. tour undertaken while communism still held sway in Czechoslovakia:

Again we had Vaclav Havel, of course, and what did I have to say about the censorship, and the unjustly prosecuted and persecuted…. I responded to all these truthful, wounding questions, trying to say I was here to discuss literature, but they said literature had to reflect life, and I’d hoisted myself on my own petard when I’d said a moment ago that Truth ought to be told, whatever the cost…

In the new atmosphere of freedom and openness after November 1989, Czech intellectuals resurrected these questions. They provoked a profound response from the writer.

"He recognized only aesthetic criteria; only beauty justifies the world, the existence of man, the existence of a writer. And everyone can do beauty, even the guys sitting at the beer hall.”

Indeed, Hrabal’s most unsparing self-assessment was delivered in a letter titled “Total Fears.” It was a piece sparked in part by an essay (“The Two Hrabals”) published in the newspaper Literární noviny by Czech novelist Ivan Klíma in 1990.

Recalling a Danish journalist’s questions about his experiences after 1968 in the essay, Hrabal writes:

My dear Danish lady, that’s the start of my little Calvary, what you call totalism, totalitarianism … and now go home, thank you for making me go over all those fears and dreads, those little totalitarities, which might just have driven me out of my wits, had it not been for this Velvet Revolution…

In “Total Fears,” Hrabal opens a window onto the shabby and corrosive good cop/bad cop act played upon him by authorities in those years. He describes the lures and petty traps and snares deployed by those in power in excruciating detail – and unmasks the useless deceptions behind them. Pressures to inform. Books cancelled. Films abandoned.

Hrabal’s willingness to explore the utter humiliations and failures of a great writer tangled up in the worst of history is what makes “Total Fears” a crucial document.

It is not a brave story. That is the point. Indeed, Hrabal concludes the essay with the observation that "this nation has in its genes what I have in mine... an inclination for booze and for Communism..."

Yet there is immense courage in "Total Fears." It is Hrabal's last great reckoning with his own story -- told with his literary genius, warts and all. It is also a letter in which art conquers fear. In public.

Epilogue

U Zlateho Tygra still opens every day at 3 p.m. in Prague’s Old Town. Tourists always find it hard to claim a seat.

On her first trip back to Prague in 2005, Gifford visited the famous beer hall once again. She saw a life-sized image of Hrabal that hung on the wall, visible as patrons entered. “It was as if he was there,” she says. “I can still hear his voice, and I can remember his gestures.” (The pub now also boasts a bust of the writer.)

Letters to April was the capstone to a brilliant career. Hrabal’s embrace of changing times and willingness to confront his past was an act of literary and moral courage.

A few years after Hrabal finished Letters to April, Czech President Vaclav Havel took U.S. President William J. Clinton to U Zlateho Tygra during his state visit to Prague in January 1994. Clinton drank a beer and ate a schnitzel in the pub after a chilly evening’s walk across the Charles Bridge.

Havel ensured that Hrabal would be there, too, and eventually called the writer over to their table. Czech news agency CTK’s report on this symbolic encounter included Hrabal’s observation to Clinton that “Prague is a city of concealed heart attacks and affectionate dressmakers.”

Over a cup of tea, Gifford acknowledges that she has not readily embraced her own part in this literary drama. “It's really kind of a hidden part of my life,” she says. “I have 21-year-old twins. They know very little about this. They're not terribly impressed by their mother who knows Russian.”

“He gave me an oversized volume of Georgia O'Keeffe’s flowers and inscribed it: ‘To my muse.’ You know, artists have different muses at different times, and, so, maybe, for a time, I was one to him. I meant something.”

Richard Byrne is the editor of The Wilson Quarterly.

Quotations from Bohumil Hrabal’s Dopisy Dubence are from a selection of the Letters to April translated by James Naughton, and published in English as Total Fears by Twisted Spoon Press.

Cover Photograph: Wenceslas Square, Prague, November 22, 1989. Wikimedia Commons User Gampe; (CC BY 3.0)