Winter 2008

How Freud Conquered America, Then Lost It

– Charles Barber

Bizarrely, it was World War II that brought psychiatry, and more specifically, psychoanalysis, into the mainstream of American culture.

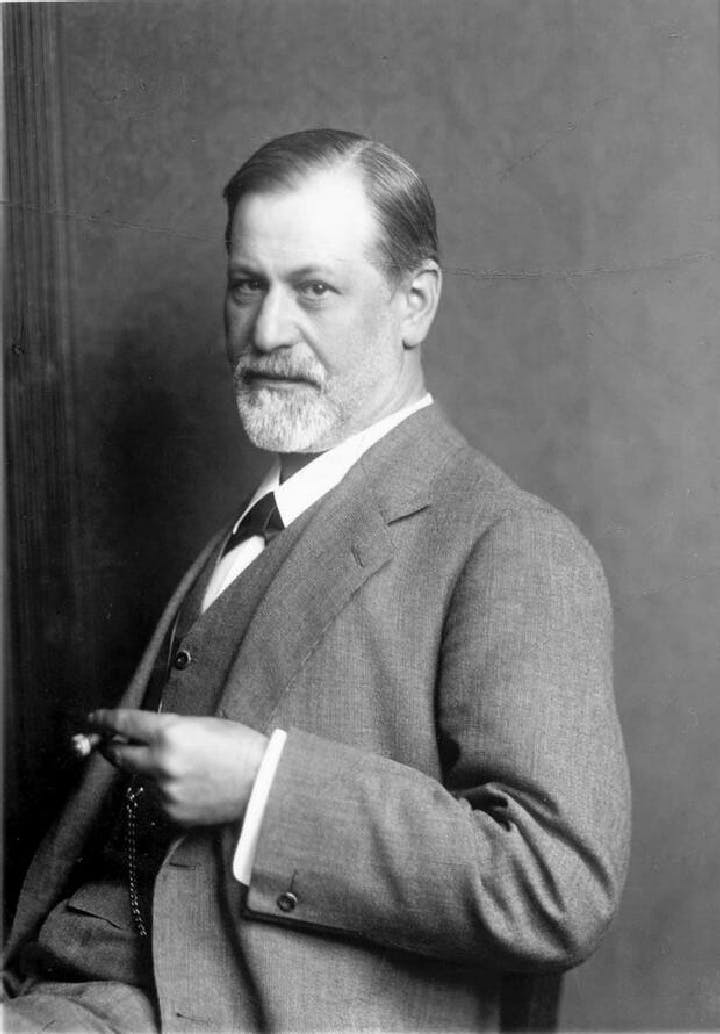

Psychoanalysis was introduced to the United States in 1909 when Sigmund Freud (accompanied by Carl Jung) delivered a famous lecture at Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts,but its influence grew fairly slowly for the next three decades. Bizarrely, it was World War II that brought psychiatry, and more specifically, psychoanalysis, into the mainstream of American culture.

During the war, for the first time in any national conflict, all recruits and draftees were screened by psychiatrists and physicians for their mental fitness. An astounding number of men—at least 1.1 million and perhaps as many as 1.8 million of the 15 million men evaluated—were rejected because of psychiatric and neurological problems. The war then produced an unprecedented stream of new patients for psychiatry: an endless supply of, to use the euphemism of the day, “battle fatigued” soldiers suffering from guilt, anxiety, and terrifying flashbacks. There were 1.1 million admissions for psychiatric disorders in military hospitals over the course of the war.

There was no coherent system of care to treat this unprecedented amount of anguish other than psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic practices and concepts were directly infused into military policy beginning in 1943, when William C. Menninger, an outspoken and articulate member of the Topeka Psychoanalytic Society, was appointed chief military psychiatrist. His ability to act as psychiatry’s salesman, both during and after the war, was helped immeasurably by his hyper-normal, squeaky-clean, Chamber of Commerce image. Within two years, Menninger assertively brought psychiatry into the mainstream of military life.

In 1944, he issued a bulletin for Army physicians, “Neuropsychiatry for the General Medical Officer,” in which the role of the subconscious in symptoms was explained, as well as the influence of infancy and childhood on adult character. Menninger’s recommended treatment methods for war neurosis included hypnosis and psychoanalytic therapy. In 1945, Menninger introduced an entirely new diagnostic nomenclature for the field. He created new categories specifically geared to incorporate the war experience, such as “transient personality reactions to acute and special stress,” which included “combat exhaustion” and “acute situational maladjustment” as diagnoses. The section on neurosis was lifted directly from Freud, with sections on repression, conversion (the expression of psychological distress as physical complaints), and displacement (the shifting of emotions from the original object to a more acceptable substitute). Menninger’s taxonomy had influence far beyond the war, becoming the basis for the American Psychiatric Association’s first diagnostic manual in 1952, the direct predecessor of today’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals.

The war also saw the advent of new treatment techniques. Group therapy was invented by beleaguered and overwhelmed medical staff, and it showed great promise for soldiers suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder. It has been suggested that one of the reasons that group therapy worked so well is that it broke down the hierarchies of military life and the prewar social structure. Medical staff rarely wore white coats, and patients and staff referred to one another by their first names.

The experience and trauma of war bolstered belief in the environmental causes of mental illness. Genetic and hereditary explanations lost substantial ground in the face of the demonstrable evidence of the damage that experience could do.

In the optimistic glow immediately following the war, Americans really did believe that psychoanalysis could help make the world a better place. In 1945, Menninger could write that “psychiatry, for better or worse, is receiving a tremendously increased interest. This is manifest on all sides by articles in magazines, in the newspapers, frequent references to psychiatry and psychiatric problems on the radio and in the movies.” Shortly thereafter, the central dilemma of the psychoanalyst was identified in the journal Daedalus: There weren’t enough of them to be everywhere at once. It was seriously argued that if only statesmen were to go through psychoanalysis there would be no more wars, and articles in psychiatric journals pondered the psychoanalytic implications of President John F. Kennedy’s death for the nation.

How soon, and how easily, it would all crumble away.

If this portrait sounds a little underwhelming, don’t blame microcredit. The real issue is that we so often underestimate the severity and inertia of global poverty. Natalie Portman may not be right when she says that an end to poverty is “just a mouse click away,” but she’s right to be supportive of a tool that helps soften some of poverty’s worst blows for many millions of desperate people.

It is fashionable nowin academic psychiatry to condemn the fancies of the last century. “All sciences have to pass through an ordeal by quackery,” wrote the psychologist Hans Eysenck. “Chemistry had to slough off the fetters of alchemy. The brain sciences had to disengage themselves from the tenets of phrenology. . . . Psychology and psychiatry too will have to abandon the pseudo-science of psychoanalysis. . . and undertake the arduous task of transforming their disciplines into a genuine science.

“Psychology itself is dead,” writes Michael Gazzaniga, a prominent neuroscientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in The Mind’s Past (1998). “Today the mind sciences are the province of evolutionary biologists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, psychophysicists, linguists, computer scientists—you name it. . . . The odd thing is that everyone but its practitioners knows about the death of psychology.”

Ironically, Freud essentially predicted what would happen—that is, he predicted his own death. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1924), he wrote about psychoanalysis: “The deficiencies in our description would probably vanish if we were already in a position to replace the psychological terms with physiological or chemical ones. We may expect [biology] to give the most surprising information and we cannot guess what answers it will return in a few dozen years of questions we have put to it. They may be of a kind that will blow away the whole of our artificial structure of hypothesis.”

Freud, it turns out, still has at least one lesson for today’s biopsychiatry enthusiasts: humility.

* * *

Charles Barber worked with the homeless mentally ill in New York City for 10 years. He is a lecturer in psychiatry at Yale University and the author of Songs From the Black Chair: A Memoir of Mental Interiors. This essay is adapted from his new book, Comfortably Numb: How Psychiatry Is Medicating a Nation.

Cover photo courtesy of Flickr/aly