Winter 2008

Moving: A Great American Tradition

– Christopher Clausen

Whether in covered wagons or station wagons, Americans have always hit the road, driven by the belief that a better life lies over the hill and around the bend.

Moving is one of life’s most stressful, time-consuming, and expensive experiences. It’s also a sacred American rite, our version of the ancestral adventures of immigration and the frontier. Unless prompted by disaster of one sort or another, moving may be the most important form the individual pursuit of utopia can take, a brave and insouciant gamble that the future will be tangibly better than the past. If owning your own home is often described as the American dream, aspiring to a bigger and better one is an expression of the national faith that the best is yet to come. A new house is a new life.

To keep searching for the place where we will at last feel truly at home, truly ourselves, is to throw the dice with a recklessness sometimes reminiscent of Pickett’s Charge. Conversely, to stay put for decades at a time is to be unimaginative, a bit stodgy, almost European in one’s avoidance of risk. No wonder adversity in the subprime mortgage market is causing such loud and lingering rumbles. What is at stake is not only the stability of the larger economy but something psychologically even more important—a shared ideology of constant and universal mobility, the conviction that anyone who can plunk down five percent has an inalienable right to the pursuit of real estate.

According to an often-quoted figure from the U.S. Census Bureau, the statistically average American moves 11.7 times in a lifetime. The better educated and more affluent tend to move longer distances. About 60 percent of native-born Americans live in the state where they were born, which means that 40 percent don’t. Between 2005 and 2006 some 40 million people changed addresses, almost 14 percent of the entire population, which is actually below the historical average for the period since the government started keeping records in 1948. One reason for the small decline may be the aging of the nation (older people move less); another is the rise in homeownership (owners move less often than renters, though, according to real estate professionals, they still take flight after an average of five to seven years). A third reason may be that most of us now own such a godawful amount of stuff that the mere thought of packing is unbearable.

Revealingly, of the many motives people give for moving, the desire for new quarters is overwhelmingly the most common. Moving for practical reasons such as a change of job or of family circumstances is less prevalent than relocating out of an urge to climb the housing ladder. Acquiring a bigger, more comfortable house, or one in a preferable location, seems to be a nearly inevitable corollary of ownership as soon as one can afford it—maybe sooner, judging by the number of home loan defaults recently. Anything with less than 2,000 finished square feet and two full baths is apt to be described by real estate agents as a “starter home,” while “McMansion” has been rapidly transformed from a term of derision employed by affluent intellectuals to a more-or-less neutral name for the large, highly visible tract houses that much of the middle class aspires to. If what you really yearn for in life is an 8,000-square-foot vinyl-sided simulacrum of the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg with twin heat pumps and garaging for six cars, there are a whole lot of people who share your taste and a corresponding number of builders who can make it happen, as a drive through most new exurban developments will confirm.

The risk and drama involved in pulling up stakes to head for suburbia are often underappreciated by those whose parents or grandparents made the transition long ago, as well as by cultural commentators who make their living on Manhattan Island. Yet the panic and disorientation that seize you when your whole life is in boxes and there’s no turning back represent some bond with the emotions of immigrant and pioneer ancestors. According to one survey, it takes an average of two years before the trauma of moving wears off and people feel at home again. If change in the abstract is good, as Americans are taught to believe, then uprooting yourself and your family for a new place, however humdrum and perhaps nearby, must be not only a praiseworthy act of faith in the mysterious future, but an expression of confidence that new communities can be created from scratch. After all, immigrants to America and their descendants have been doing it for more than four centuries.

Alan Wolfe, a distinguished sociologist of religion who has studied American values for a long time, places the epic 20th-century movement to the suburbs in judicious historical perspective: “No doubt selfish motives were involved in the lure of suburbia: a home of one’s own, a desire to be seen as successful, the two-car garage. But even with all that, the choice of suburbia was a choice in favor of a particular version of morality, one that resonated with utopian versions of the good life.” New York Times columnist David Brooks, the poet laureate of the contemporary exurbs, makes the same point even more emphatically: “Why do people uproot their families from California, New York, Ohio, and elsewhere and move into new developments in Arizona or Nevada or North Carolina, imagining their kids at high schools that haven’t even been built yet, picturing themselves with new friends they haven’t yet met, fantasizing about touch-football games on lawns that haven’t been seeded? . . . To grasp that longing, you have to take seriously the central cliché of American life: the American dream.” In what often seem to be the most mundane aspects of their daily lives, ordinary Americans really are searching for paradise.

My grandfather's house and garden reflected his self-creation as a fully enfranchised 20-century American.

In this respect, as in so many others, Abraham Lincoln remains the representative American. Born in a hovel in Kentucky, he moved as a child to Indiana, where his improvident father pursued a success that never came. Every reader of American history knows the anecdote in which the ambitious but penniless young lawyer, invited by a storekeeper named Joshua Speed to share his room in the frontier village of Springfield, Illinois, set down the saddlebags that contained all he owned and announced, “Well, Speed, I’m moved.” But in a fairly short time, Lincoln achieved the affluence that had eluded his father. One major result was a house, unprepossessing at first but improved and enlarged by its prospering owner, that has become a national park and a shrine for close to half a million pilgrims a year.

More than Monticello or Mount Vernon, which were built on inherited estates, Lincoln’s home represents the aspirations and accomplishments of democratic America, the land where all men are said to be created equal and a home of your own is a national promise. Lincoln’s vision of paradise, hitched to an ambition his junior law partner called “a little engine that knew no rest,” led him from Springfield to the White House. It led the nation to the two most important social enactments of our entire history, the Emancipation Proclamation and the Homestead Act. Both of them drastically enhanced the freedom of ordinary people to move at their own volition; both took effect the same day. Henceforth, geographic and social mobility would be even more closely intertwined.

Once upon a time, the proprietor of a James River plantation proudly informed me that his children were the 10th generation of their family to live in the same house, which an ancestor had begun constructing in 1723. Even in Tidewater Virginia so much continuous history in one place is unusual, and although the stability it represents holds a certain attraction (as did the spectacular property to which the plantation owner was heir), stasis seems somehow out of keeping with the main impulses of American life. Why bother leaving the Old World in the first place if you then spend eternity almost at the port of arrival? Just as we admire what we interpret as the durable harmony of so-called indigenous communities but wouldn’t dream of living such a life ourselves, so the most venerable American roots, on the rare occasions when we uncover them, seem like something we might at best pay a qualified tribute, then bury again.

To nearly all of us, real life, modern life, means moving on, not standing still. The Homestead Act, which settled much of the West with intrepid newcomers who traded backbreaking work for land of their own, is among the most admired pieces of legislation in the checkered history of Congress. By the same token, the most reviled Supreme Court opinion of recent years was the Kelo decision of 2005, in which five justices declared it constitutional for local governments (in this case the city of New London, Connecticut) to seize whole neighborhoods of modest houses through the exercise of eminent domain and turn the land over to private developers. Kelo was one of those rare cases in which both liberal and conservative voters found the majority decision outrageous. It left nearly everyone with a sour taste reminiscent of The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s novel about Dust Bowl refugees, in which the rich use the law to seize the houses and land of the poor. We all know people who started from scratch and made the desert or its equivalent bloom. Most of us, in fact, are related to them.

My paternal grandfather, the first member of his family born in the New World, was prophetically named Adam and began life in a Manhattan tenement at the corner of First Street and First Avenue. As a child, he moved repeatedly up and across town while his father tried in vain to make a decent living as a porter, shoemaker, and tailor. In desperation, the family migrated for a few years to what is now Jersey City, where they truck-farmed in an apparently idyllic interlude between hardships typical of working-class life in the late 19th century. At 12 Adam dropped out of school and went to work for a druggist, then for a succession of immigrant-owned grocery businesses, moving from one run-of-the-mill apartment to another. In 1905, at the age of 25, feeling frustrated with himself and stifled by his close German-American community, he enlisted in the Seventh Cavalry.

Incongruous a landing place as the cavalry sounds for a young man from the New York slums, the Army, then as now, was one of the most common routes to Americanization and advancement for immigrants and their children. The first thing it did for my grandfather was take him out of New York and into a more mobile, less timid America. The second was to teach him a useful trade—pharmacology. What he learned in the Army would be valuable throughout what proved to be more than a half-century in the pharmaceutical business. The civilian life he returned to a few years later was very different from the one he had left. He was not only more mature but far more familiar with life beyond the Hudson. He had learned to move. In 1910 he married my grandmother, and within a few years they had two sons, Robert and John, whose names bore no connection to the community from which their father had escaped. When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, my grandfather forbade his wife ever to speak German again at home. Meanwhile, increasing prosperity led first to a large apartment on the Upper West Side, then, when he was 40, to a house in Passaic, New Jersey, part of a post-World War I suburban development on what had been raw fields a few months earlier.

What I remember most about that modest stucco house, from visits early in my childhood, is the garden my grandfather contrived on his eighth of an acre. It was an astonishing array of neat flowerbeds, carefully balanced and bordered with an aesthetic sense that was surprising for a person of his background. Perhaps the interlude in Jersey City had left its mark, or maybe the human affinity for flowers is innate and needs only opportunity to express itself. He even remembered the birds and what a man with his experiences might easily have imagined to be their own pleasure in mobility and freedom, a utopia after their particular fashion. The dozens of brightly painted birdhouses he built over the decades became heirlooms to his children and grandchildren. My grandfather’s house and garden alike reflected his self-creation as a fully enfranchised 20th-century American.

If you spend your whole life in pursuit of paradise, you must be perpetually dissatisfied with the place where you actually live, with the result that your moves are apt to be frequent and frustrating. That’s the more feverish, less happy side of the American dream. At its most extreme, such restlessness is incapable of fulfillment in this world. After some 45 days working in space, John M. Grunsfeld, a NASA employee who helps maintain the Hubble Space Telescope, declared, “I finally found a place where I feel at home. This is where I belong: in space. It was a disappointment to have to come home, even though I wanted to see my family and friends.” Yet if he could have spent the rest of his life on a space shuttle, one suspects he would soon have found new reasons for dissatisfaction.

Whatever there may be of utopia appears to lie in the search itself. Americans always believe the next place will be better.

On a more earth-bound level, I had an uncle, the son of immigrants, who could never stand to live in the same location for more than a few years. His successful career in advertising and public relations allowed him to move as often as he liked—when he wanted to try out a distant city, there was always a job waiting for him. This perpetual need to be on the move drove his wife (and eventually their two children) crazy. They began married life in New York in the early 1950s. During the years when I knew them best, they successively inhabited a turn-of-the-century mansion with a carriage drive in an exurb of Cleveland, another big house in Pittsburgh, a farmhouse in the Berkshires, something similar in Bucks County, and—after my uncle retired from the last of his many jobs—an elegant antebellum house in a sunny Savannah square. But something went wrong again. The taxes were too high or there were too many tourists, or perhaps it was termites. They sold the house and moved first to an apartment, then to a modern townhouse nearer the beach.

Surely, we thought, this would be the end of it. But my uncle felt the need for one last, spectacular move. A northeastern liberal, he suddenly discovered that he found Georgia politics offensive. His son lived in San Francisco. What could be more stereotypically American than a move to California just before you turn 80? Never mind the fact that neither he nor his wife had ever lived west of Chicago. My aunt’s reluctance stood no chance at all against the compulsion that had possessed her husband for so long. Off they went once more.

For people like him, the destination seems to matter less than simply moving on—the sheer act of assuming a new identity in a new place, adapting to a new community, making friends again, searching out new stores and libraries, banks and doctors, routes and routines. Whatever there may be of utopia appears to lie in the search itself.

Nonetheless, immigrants and natives alike, we always believe the next place will be better. Whatever happens to credit, to border enforcement, or to a family over a span of generations, the gamble works out often enough for Americans to remain the world champions of voluntary mobility and the special variety of optimism that underlies it. Even Steinbeck’s migrant Joad family found some of their hopes fulfilled at the end of their epic trek across the Southwest.

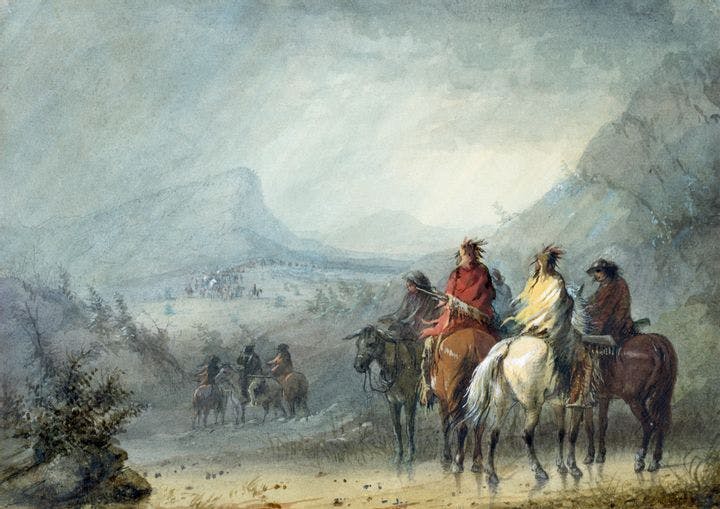

Naturally, there are exceptions. Think of the most disastrous move in history, the Donner family’s carefully planned relocation from Illinois to California in 1846. After taking a wrong turn in the desert, the Donners and their fellow travelers spent a brutal winter trapped in the Sierras, where the survivors avoided starvation by expedients that turned their misfortunes into one of the best-known legends of the frontier. Experiences like that would have eaten up the resolve of a less driven nation. Yet the widely publicized story of the Donner Party deterred few 19th-century Americans from setting off beyond the wide Missouri. And so it continues, whether the projected move is to the suburbs or the desert, across the street or across the country. An insatiable national urge that incompetent navigation, hostile Indians, blizzards, hunger, and even cannibalism couldn’t stop is unlikely to be slowed for long by misdoings in the mortgage market.

* * *

Christopher Clausen is the author of Faded Mosaic: The Emergence of Post-Cultural America, among other books. At present he lives in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons