Winter 2009

Captain America

– Max Byrd

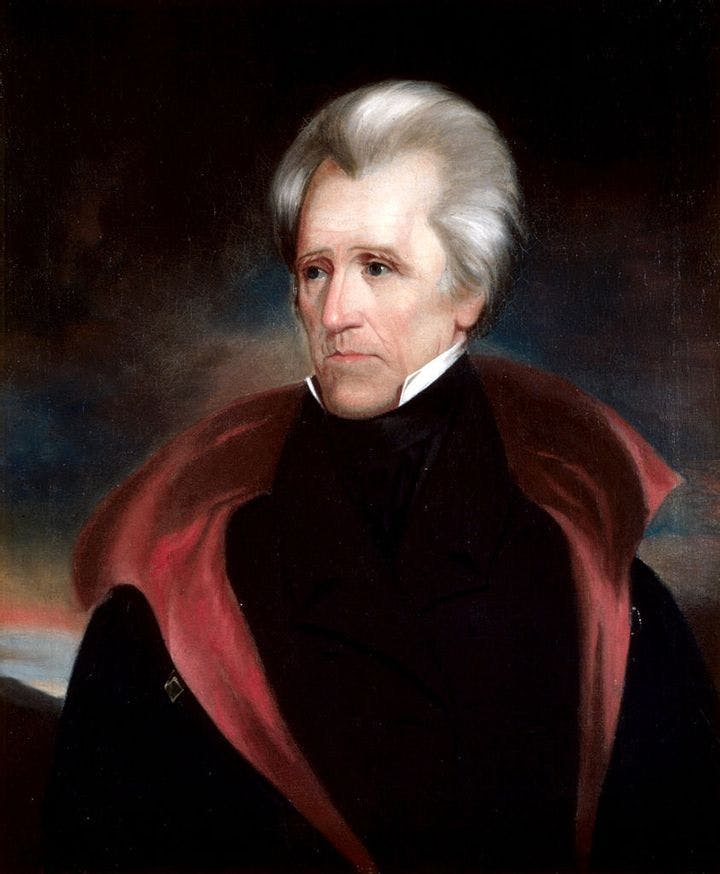

Max Byrd says that biographer Jon Meacham sums up Andrew Jackson's antithetical personality: "commanding, shrewd, intuitive yet not especially articulate, alternately bad-tempered and well-mannered."

There is reason to believe that Herman Melville modeled his Captain Ahab after the perpetually furious, sublimely obsessive seventh president of the United States, Andrew Jackson.

It is an easy association to make—Ahab, the man of “fixed purpose” and an “iron soul,” Jackson the “Iron President,” as his contemporaries called him, not only for his triumph over physical infirmities (he was probably the only president to endorse a patent medicine), but also for what one eulogist described, without irony, as his “amazing inflexibility of will.”

Ahab was stark, staring mad, of course, hurling defiance at the Almighty and the Whale, imagining the day his own head would turn slowly to solid metal, a “steel skull . . . that needs no helmet in the most brain-battering fight.” In Jackson’s case, though plenty of his enemies thought him crazed and even insane, those closer to him suspected that underneath his ferocious glare and temper Old Hickory was a calculating politician, fully rational and in control.

Jon Meacham is something of a connoisseur of contradictions. A native of Tennessee who resides in New York City, a working journalist with a scholarly bent, he has written extensively in Newsweek—where he is the editor—on the tension between faith and reason in American life. He is also the author of an elegant and sensitive study of the friendship between the cool, secretive Franklin Roosevelt and his mighty opposite, the warm, transparent Winston Churchill.

It is no surprise, then, that his book about Andrew Jackson’s years in the White House should stress the antithetical quality of Jackson’s personality. “Commanding, shrewd, intuitive yet not especially articulate, alternately bad-tempered and well-mannered,” Meacham writes in his prologue, Jackson “could seem savage, yet he moved in sophisticated circles with skill and grace.” More than one of his contemporaries had an experience like that of the New Orleans hostess who dreaded inviting the “wild man of the woods” for dinner, yet afterward found her guests breathless with admiration: “Is this your backwoodsman? He is a prince!”

He is a prince, Meacham makes clear, who began as a pauper. The first chapter of American Lion provides a concise account of Jackson’s wretched early life in the Carolinas after his birth in 1767, beginning with the deaths of his parents and his two brothers and his cruel boyhood service against the British in the Revolution. A few more pages take up his move to Tennessee, his fiery courtship of Rachel Donelson (separated but not yet divorced from her first husband), his duels, his Indian wars, his glorious victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.

But Meacham is eager to get to the presidency and what he sees as Jackson’s permanent transformation of that office. After a journalist’s appreciative glance at the so-called Corrupt Bargain of the 1824 election, when John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay apparently collaborated in secret to defeat the Tennessean, he begins his narrative proper with Jackson’s revenge on Adams and his triumphant election in 1828.

If, as is sometimes said, Thomas Jefferson was the great theoretician of democracy, envisioning a smiling republic of sober, learned farmers like himself, Andrew Jackson, storming like a comet out of the west, was the great coarse, brawling, uns carriage was rolling sullenly north toward Boston, Jackson’s rampageous followers, in what Meacham calls a “legendary scene in American history,” were crowding by the hundreds into the president’s mansion for a chaotic victory celebration, quite literally trashing the White House. The “Majesty of the People,” wrote the horrified Jeffersonian Margaret Bayard Smith, “had disappeared, and a rabble, a mob of boys, negroes, women, children, scrambling, fighting, romping” had taken its place.

Meacham is clearly fascinated and moved by what the French call the grand lines of history—here the violent, torrential expansion of democracy in the early 19th century, the nearly apocalyptic clash of vision and social classes that would soon bring the Union to the brink of permanent dissolution. He has a gift for clarity and the telling quotation, and he does a wonderful job of breathing life into his long-silent actors. But first he must rehearse, like all students of Jackson’s administrations, that most curious of presidential scandals, the Eaton Affair.

Rachel Jackson died shortly before Jackson took office, driven to her grave, so he believed, by slander and gossip about her first marriage and divorce. When his secretary of war, John Eaton, married the former barmaid Margaret O’Neale, many in Washington, including Jackson’s own niece and nephew, thought that in the past Margaret had been (in the curious Victorian phrase) no better than she should be, and they treated her with a disruptive coolness. Jackson, however, saw only another slandered woman (“She is as chaste as a virgin!”), and official Washington quickly divided into Puritans and Cavaliers. Then, for more than two years the wheels of government rocked back and forth, so mired in rumor and ill will that some cabinet members and their wives refused to speak to each other. Hard as it is to picture now, social and political gatherings at the White House were conducted—or dissolved—in an atmosphere of paralyzing rectitude and disdain. In April 1831 all but one of Jackson’s cabinet resigned in frustration, and suddenly, as Martin Van Buren put it, “the Eaton malaria” was past.

From this point on, Meacham’s narrative builds in tension and speed. He is particularly good on the ominous battle between South and North over tariffs, a prelude to civil war marked by South Carolina’s shrill and repeated threats of secession. (South Carolina, the anti-secessionist lawyer James Petigru once mused, was “too small for a republic, and too large for a lunatic asylum.”) He lays out with saintly clarity the intricacies of Jackson’s long populist struggle to reduce the power of the United States Bank and its president, Nicholas Biddle. And he writes with compassion and anger—and a baffled sense of paradox—about Jackson’s decision to forcibly remove Cherokees and other Indians from their homes in the South to reservations west of the Mississippi, which resulted in the infamous “Trail of Tears”: Jackson “could be both unspeakably violent toward Indians and decidedly generous.” But Meacham comes very late to a discussion of Jackson’s chilling view of slavery, noting perhaps too judiciously that the president was “blinded by the prejudices of his age” (there was no shortage of abolitionist voices in Jackson’s America). In 1837, at age 69, unapologetic and as combative as ever, Jackson left the White House, to be succeeded by Van Buren.

Biographer Jon Meacham sums up Andrew Jackson's antithetical personality: "commanding, shrewd, intuitive yet not especially articulate, alternately bad-tempered and well-mannered."

As a running counterpoint to politics, Meacham draws an intimate picture of the ever-shifting, ever-dramatic Jackson household, both in Washington and back in Tennessee. In particular, Jackson’s niece Emily Donelson, official hostess for many of his White House years, emerges as an utterly charming if ultimately tragic figure. A foreign diplomat compliments her dancing with undiplomatic condescension: “I can hardly realize you were educated in Tennessee.” To which, according to the story, Emily smoothly replies: “Count, you forget that grace is a cosmopolite, and like a wild flower is much oftener found in the woods than in the streets of a city.” She died of tuberculosis in Nashville in 1836 at the age of 29, with neither her husband nor her uncle present.

Few readers will disagree with Meacham’s central premise, familiar to scholars, that Jackson “expanded the powers of the presidency in ways that none of his six predecessors had.” He is thinking of Jackson’s bold use of the veto and his unblinking assertion that the president was elected by all the people, not just the states, and therefore had priority over Congress—a clear reversal of the Founders’ ideas. He is also thinking of Jackson’s direct appeals to the people through newspapers (the “media” of 1828), his extensive and private circle of advisers known as the “Kitchen Cabinet,” his melodramatic and compelling personality.

A surprising number of Jacksonian issues are with us today—the recklessness and arrogance of bankers, the rise of the evangelical Right—but none more central and important than the expansion of presidential power year after year, and the parallel dwindling away of Congress to a series of transoms through which lobbyists submit their bids. Jackson’s expansion of executive power was much admired by later presidents, particularly the two Roosevelts and Truman, and Meacham is surely right that most of it is irreversible. But though he tries to view this development calmly, even philosophically, the distance between iron will and tyranny is not easy to measure. “The Bank . . . is trying to kill me,” Jackson once cried out in rage, “but I will kill it.”

Apart from some material on the Donelson family, little here is new, but everything is so carefully and brilliantly set out for the general reader that Meacham’s book should now become the biography of choice. He concludes with Jackson’s retirement to Nashville and his late conversion to church membership just before his death in 1845. An epilogue on the famous equestrian statue of Jackson across from the White House offers a warm and reassuring image of the old hero as a strong-willed but loving father to his people.

Some readers will see the image differently, however. It is also possible to imagine from the evidence that Jackson’s character was less benign, founded on a dangerous core of anger that never went out and fueled by an inexhaustible ambition to dominate and control. If he was often compared by his contemporaries to Napoleon, it was not solely because of military ability. If he was like Ahab in his astonishing, mesmerizing energy and force of will, it is well to recall that in the end Ahab’s ship and all its men, save Ishmael, perished.

* * *

Max Byrd is the author of the historical novels Jackson (1997), Jefferson (1993), Grant (2000), and Shooting the Sun (2004).

Reviewed: American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham, Random House, 483 pp, 2009.

Portrait by Ralph Elaser Whiteside Earl, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons