Winter 2009

Spice and Status

– The Wilson Quarterly

New research reveals that spice was not used in medieval times to mask the taste of rancid meat, but rather to infuse good meat with the sweet-sour flavor that was the epitome of the fashionable cooking of the era.

The cuisine of the Middle Ages, with its tincture of ambergris and malaguetta, may not inspire many start-up restaurants, but the long-held explanation for the powerful flavors of the age turns out to be a historical myth. Meat during the period was not so rancid that its taste had to be masked with spices, writes Paul Freedman, a Yale historian. Any medieval lord rich enough to afford spices could easily have bought fresh meat.

Spices were both the status symbols and high-yield investments of their day. Expensive and coveted, they were the mark of a wealthy household. Outrageously profitable, spices drove Europeans to their first overseas adventures. Pepper purchased in India for three Venetian ducats could fetch 80 ducats in Europe. Christopher Columbus was on the trail not only of gold and silk but also spices when he set off for what became America. The purpose of procuring spices, however, was not to mask the taste of bad meat, but rather to infuse good meat with the sweet-sour flavor that was the epitome of the fashionable cooking of the era.

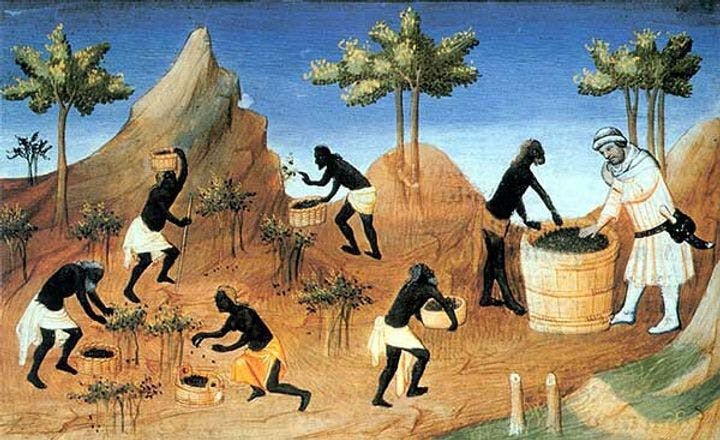

Cinnamon, nutmeg, and sugar, now most commonly used in desserts, seasoned the main courses at medieval banquets. They were paired with a selection of peppers, including African malaguetta, Indian long pepper, and galangal—the strong spice now known mainly through Thai cooking, to flavor thin sauces often based on almond milk. Fashionable food was prepared with an eye toward achieving a pleasant color as well as taste. Rich hues could be achieved with such spices as cinnamon and saffron. Contrary to the conceit of movies set in medieval times, meat was not served in large haunches on racks, but was ground up and cooked, often several times, so coloring was useful.

Rarity bred prestige. When pepper became so common in the early 14th century that it was used in meals served to peasants working in the fields, it began to disappear from recipes for fine cooking. Still, cooks used spices frugally. They were occasionally used to flavor wine, then reused in sauces.

By the 17th century, European cooks had moved away from heavily spiced sauces to more intense preparations based on butter, herbs, and meat reductions. Traffic in slaves, sugar, and tobacco would eventually outstrip the spice-carrying business. Ambergris, a substance created by digestion in the hindgut of the sperm whale and considered the height of exotic taste in the 14th century, slowly fell out of favor. But spices remained important. New Amsterdam, eventually to become New York, was relinquished by the Dutch to the English in return for Run, the most remote of the Molucca islands. No wonder the Dutch wanted Run instead of Manhattan: The tiny spice island was the original home of nutmeg.

THE SOURCE: “The Medieval Taste for Spices” by Paul Freedman, in Historically Speaking, Sept.–Oct. 2008.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons