Winter 2010

America's Namesake

– Felipe Fernández-Armesto

Putting America on the Map

Renaissance sophisticates sneered. How could a sleepy little backwoods town like Saint-Dié in distant Lorraine, deep in upland pine forests, home to flax weavers and log sawyers, presume to rival the great centers of humanist learning at the beginning of the 16th century? Saint-Dié seemed too poor and remote for glory and fame. Yet under the ambitious patronage of the young Duke René, a group of learned men gathered, around the town’s printing press and cathedral library, to undertake an audacious project—overly rash, by the standards of the town’s resources. They proposed to bring out an updated edition of the most acclaimed geographic text of classical antiquity—Ptolemy’s Geography, compiled in the second century AD—and to supplement it with the new knowledge of the planet revealed by recent and current explorations. Eventually, the project collapsed. The scholars died or dispersed, and the focus of Ptolemaic research moved away from Saint-Dié. Meanwhile, however, the effort had changed the world by generating two maps of enormous influence and significance—the work of jobbing humanists who probably had been fellow students.

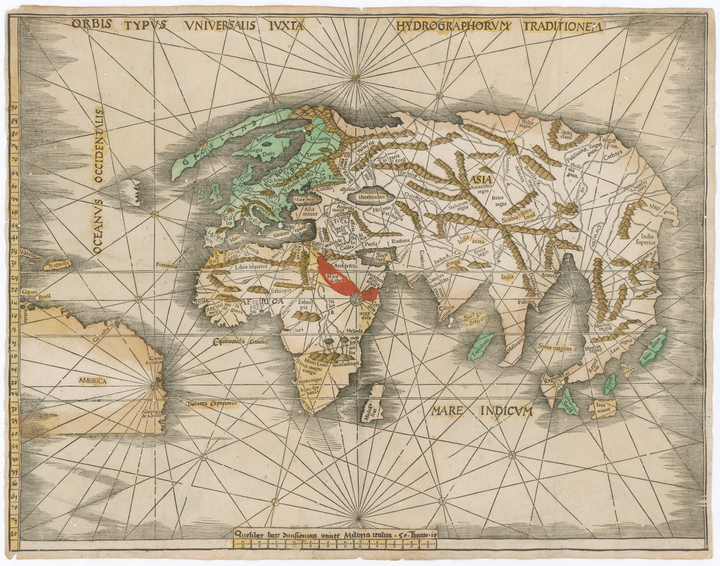

The world maps Martin Waldseemüller made in Saint-Dié, with the help of his colleague, Mathias Ringmann, were technically innovative. One was the world’s first printed globe. The other was a vast map, engraved in black on multiple squares of graying paper, designed to be trimmed, joined, and pasted onto a study wall. The content was innovative, too: The wall map was, as far as we know, and according to the cartographer’s own commentaries, the first to attach the name “America” to the Western Hemisphere. Its fragility condemned it to hazard—worn and scraped off a thousand walls. But one copy survived, neglected for centuries, unmounted, in an old folder in a musty muniments room in a German castle. In 1901, an erudite Jesuit schoolteacher searching for medieval Norse documents happened on it and recognized it at once for what it was. It is now the costliest treasure in the Library of Congress. In Waldseemüller’s day, however, copies abounded, helping to fix the name of “America” in scholars’ minds and on other maps.

Ironies enshroud the story. Waldseemüller and Ringmann chose the name because they revered an account of transatlantic voyages attributed to the Florentine adventurer Amerigo Vespucci. But Vespucci was not the real author of the work, which was a publishers’ confection, issued to exploit a market for marvelous travelogues. The work the humanists admired claimed that Vespucci had discovered the mainland of the New World before Columbus—a claim that turned out to be false. (In a later map, Waldseemüller suppressed all mention of Vespucci and drew attention to Columbus’s prior landfall in what the cartographer now, less catchily, called “Terra Incognita.”)

Vespucci, in any case, was not the innovative geographic visionary depicted in historical tradition: He hardly modified ideas he borrowed from Columbus and thought the “New World” was part of Asia. Moreover, Waldseemüller misread the supposed Vespucci text. Where the Florentine was credited with discovering “a fourth part of the world,” Waldseemüller understood the allusion to be to a fourth continent, to stand alongside Europe, Asia, and Africa. But all Vespucci meant, in an authentic work of his own in which he first used the phrase, was that he had navigated across 90 degrees of the surface of the globe—a “fourth part” of the total. Even this claim was probably false, but had it been true, it still would not have justified the mapmaker’s inference that Vespucci had disclosed the existence of a previously unknown continent.

The Saint-Dié set accepted Vespucci’s claims to have improved on the techniques of practical navigators in his day by using astronomical instruments to reckon a ship’s progress in terms of the motions of celestial bodies. Waldseemüller was so impressed by Vespucci’s credentials as a scientific navigator that, in the Library of Congress map, he engraved the Florentine’s portrait in a cartouche at the top, from which the navigator looks down on the world in proprietary fashion, next to a depiction of Ptolemy, equal in size and symmetrically placed. In the Renaissance, there could be no higher compliment than to feature a modern man as equal to one of the great figures of antiquity. The basis of the compliment, however, was phony. Vespucci never took an accurate astronomical reading at sea.

Tragedy followed irony. The Saint-Dié circle began to break up when Duke René died in 1508. Mathias Ringmann followed his former master to the grave in 1509, deploring the corrosive effects of his sickness on his ability to think in Latin of classical purity. By 1516, Waldseemüller was so disgusted with his own earlier work that he not only withdrew the name of America but repudiated the map that had given that name to scholarship. It was, he wrote, “filled with error, wonder, and confusion. . . . As we have lately come to understand, our previous representation pleased very few people.” He was being excessively modest; the map he valued so humbly cost the Library of Congress $10 million in 2003.

In every respect, the story of Waldseemüller’s map is impassioning: as a source of insight into the history of our knowledge of our world; as an object lesson in the gropings and failings of Renaissance humanism; as a detective story in which a vital document mysteriously disappears to be startlingly rediscovered; as an instance of the role of chance and error in making history; as a cautionary tale of the overlap of obscurity and influence, notoriety and fame; and as a case study of stunning historical supercherie. In The Fourth Part of the World, Toby Lester, an Atlantic contributing editor, tells the story better than anyone has told it before. But he devotes little more than a quarter of the book to the map itself, choosing rather to locate it in an immense context of 300 years of European efforts to picture the globe in the late Middle Ages and early modern period.

Focusing on the work of the 13th-century English monk Matthew Paris, he starts with the high-medieval project of encompassing the whole of knowledge in encyclopedic compendia. He then turns to the effects of encounters with the Mongols in enlarging European knowledge of Asia, before examining the efforts to explore the western ocean that began in Genoa in 1291, and continued for two centuries in the seaports of Mallorca, Portugal, Castile, and other places on Europe’s Atlantic rim. He also covers the impact of the rediscovery of classical geographic texts, and the contributions of learned armchair cosmography among scholars in Florence and Portugal (though he skips over the importance of Nuremberg as a center of geographic inquiry and of Bristol as a launch pad of exploration).

Understandably, in attempting to cover such a huge swath of highly problematic material, Lester relies on the work of professional scholars, whom he treats, I think, with excessive respect. One longs for him occasionally to seize and shake his authorities, and treat them more searchingly and critically, especially on Columbus and Vespucci, in regard to whom much of the scholarly tradition has been discredited. Even so, Lester’s deftness in narrating a long and complex tale is impressive: fluent, clear, well informed, and perfectly paced. In short, he is an example of a phenomenon increasingly embarrassing to professional historians: a journalist who writes history better than we can.

When he gets around to Waldseemüller’s map, Lester makes a formidable contribution. His convincing reasoning sheds new light on the relationship between “Ringmann, the writer, and Waldseemüller, the mapmaker.” His analysis of the learned puns encoded in the Greek version of the name of America proposed in the Saint-Dié cosmographers’ Introduction to Ptolemy is satisfying. His account of Waldseemüller’s cartographic sources is enlightening. His study of the map from an iconographic point of view, though very selective, is challenging. (He sees, not entirely convincingly, the imperial eagle as an organizing shape hovering around the map.) Some aspects are omitted: It would have been of great interest, for instance, to read Lester’s thoughts on the many curious legends and labels included in the map, in which information about animals is puzzlingly prominent. The entire treatment is tantalizingly brief: It is a pity the author did not give himself space to broach more of the problems and deepen the analysis.

Of the unposed questions, the most intriguing, perhaps, concerns the date of the printing of the Library of Congress copy. No one can doubt that it is genuinely an early impression of the long-lost map Waldseemüller published in 1507. But the surviving example was made from a well-worn plate at an unspecified time, perhaps years after the first printing. This fact raises a potentially headline-grabbing possibility. In 2003, the Library of Congress invested an unprecedented sum to acquire a map whose status as the oldest to bear the name of America is open to challenge.

For more than a hundred years, the John Carter Brown Library, affiliated with Brown University, has housed a rival: an undated work by the same cartographer, showing an outline virtually identical to that of a map known to have been printed in 1513. This version, however, is unique—or at least different from the rest of Waldseemüller’s output of that year—in that it includes the name “America.” Lester dismisses this map’s claims to priority in a brief appendix; but until the possibilities of scientific analysis, especially of hyperspectral imaging, are exhausted, the printing dates of both maps remain open to question. There may be twists yet to come in the tale of “the map that gave America its name.”

***

Felipe Fernández-Armesto is a history professor at the University of Notre-Dame. His books include Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America (2007) and 1492: The Year the World Began (2009).

Reviewed: "The Fourth Part of the World: The Race to the Ends of the Earth, and the Epic Story of the Map That Gave America Its Name" by Toby Lester, Free Press, 2009.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons