Winter 2010

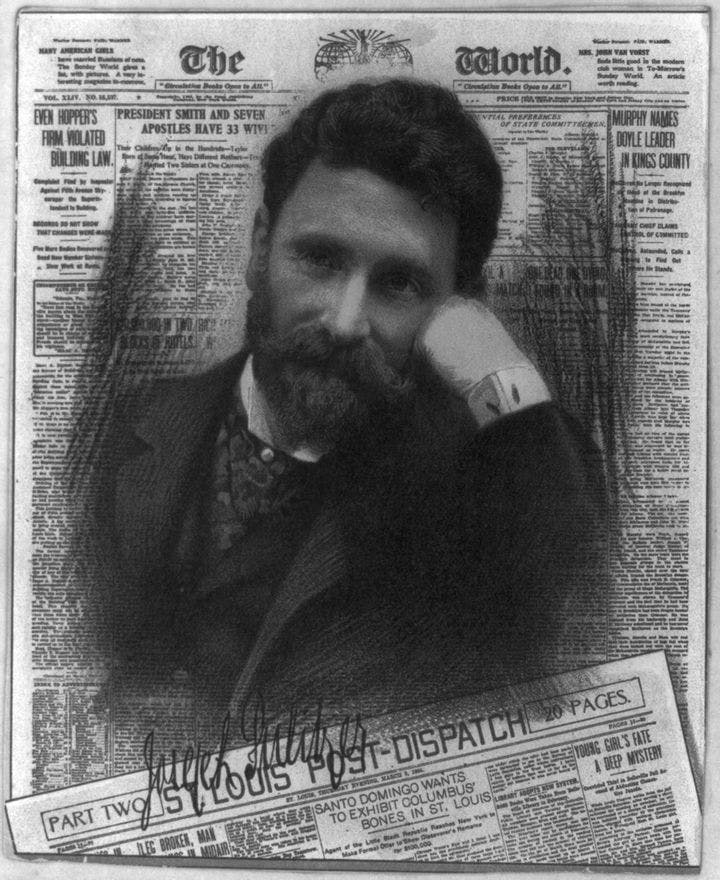

Pulitzer's World

– James McGrath Morris

Today, as newspapers are shuttered and reporters panhandle for work, it's worth remembering Joseph Pulitzer, whose taste for sensationalism and sense of public service midwifed American journalism into the modern era.

In May 1883, after attending a funeral in Vermont, New York World reporter James B. Townsend returned to Park Row, the stretch of buildings across from New York City Hall that served as America’s Fleet Street. There, the Herald, the Tribune, and the Sun, along with less known papers such as the Times and the World, plied their trade within earshot of one another. With the exception of the Sun—a vanguard of the penny press that covered urban tales and partisan politics—the papers produced a dignified and subdued tally of the latest goings-on in American politics, foreign capitals, finance, and polite society that was consumed by those with the economic wherewithal to spend as much as a nickel.

When Townsend had left, a few days earlier, the World was on its last legs, and appeared unlikely to be rescued by its owner, the financier Jay Gould. Townsend, one of the few reporters still with the paper, was startled by what he found upon reaching the World’s offices. “It seemed as if a cyclone had entered the building,” he recalled later, “completely disarranged everything, and had passed away leaving confusion.” Striving to avoid collisions with messenger boys exiting with urgent deliveries, Townsend made his way to the city room and found his colleagues running around excitedly. He asked the general manager about the cause of all the commotion.

“You will know soon enough, young man,” the fellow replied. “The new boss will see you in five minutes.” He then glanced up at Townsend and added. “After us the deluge—prepare to meet thy fate.”

The new owner was Joseph Pulitzer, a 36-year-old Jewish Hungarian immigrant who had come to New York City from St. Louis, where in the short span of five years he had transformed a bankrupt evening newspaper into a moneymaking, politician-breaking, must-read sheet. Pulitzer was part of a new order of journalism—lively, independent, and crusading—that was growing in cities outside New York, like a stage play previewing out of town, working out the kinks while awaiting its chance to open on Broadway.

Townsend was summoned to Pulitzer’s office. Dressed in a frock coat and gray trousers, Pulitzer stared at him through his glasses. “So, this is Mr. T.,” he said. “Well, sir, you’ve heard that I am the new chief of this newspaper. I have already introduced new methods—new ways I propose to galvanize this force: Are you willing to aid me?”

Almost as if the breath had been sucked from him by Pulitzer’s vigor, Townsend stammered that he would like to remain on the staff.

“Good, I like you,” replied Pulitzer. “Get to work.”

During the following days, editors and reporters arriving in the early morning found Pulitzer already in his office, often toiling in his shirtsleeves. When the door was open and he was dictating an editorial, recalled one man, “his speech was so interlarded with sulphurous and searing phrases that the whole staff shuddered. He was the first man I ever heard who split a word to insert an oath. He did it often. His favorite was ‘indegoddampendent.’ ”

As the staff settled in for the day’s work, they couldn't escape Pulitzer. No detail was so small that he considered it beneath his attention. He was once overheard disputing the number of cattle an editor estimated had arrived in New York from the West the previous day.

In the short span of five years he had transformed a bankrupt evening newspaper into a moneymaking, politician-breaking, must-read sheet. Pulitzer was part of a new order of journalism—lively, independent, and crusading—that was growing in cities outside New York, like a stage play previewing out of town, working out the kinks while awaiting its chance to open on Broadway.

At first, Pulitzer sought solely to inculcate in his staff the principles by which he believed a paper should be written and edited. This effort, however modest it may seem, is how the World began on its path to becoming the most widely read newspaper in American history. (To match the reach, in comparative terms, of the million-copy circulation of Pulitzer’s World, today’s New York Times would have to increase its paid readership by 300 percent.) In an era when the printed word ruled supreme and 1,028 daily newspapers across the country vied for readers, content was the means of competition. The medium was not the message; the message was.

The paper abandoned its old front-page headlines. Bench Show of Dogs: Prizes Awarded on the Second Day of the Meeting in Madison Square Garden, which appeared on May 10 in the last editions before Pulitzer assumed control, was succeeded on May 12 by Screaming for Mercy: How the Craven Cornetti Mounted the Scaffold. Two weeks later, the World’s readers were greeted with the words Baptized in Blood, atop a story that, with the aid of a diagram, detailed how 11 people were crushed to death in a human stampede when panic broke out in a crowd enjoying a Sunday stroll on the newly opened Brooklyn Bridge. Pulitzer’s dramatic headlines made the World stand out from its competitors like a racehorse among draft horses.

To match the reach, in comparative terms, of the million-copy circulation of Pulitzer’sWorld, today’sNew York Timeswould have to increase its paid readership by 300 percent.

If the headline was the lure, the copy was the hook. Pulitzer could craft—or teach his editors to craft—all the catchy headlines he wanted, but it was up to the reporters to win over readers. He admonished his staff to write in a buoyant, colloquial style consisting of simple nouns, bright verbs, and short, punchy sentences. The “Pulitzer formula,” if there was one, was a story written so simply that anyone could read it, and so colorfully that no one would forget it. “The question, ‘Did you see that in the World?’” Pulitzer instructed his staff, “should be asked every day, and something should be designed to cause this.”

The World’s stories were animated not just by the facts the reporters dug up but also by the voices of the city they recorded. Pulitzer drove his staff to aggressively seek out interviews, a relatively new technique in journalism. Leading figures of the day, accustomed to a high wall of privacy, were affronted by what Pulitzer proudly called “the insolence and impertinence of the reporters for the World.”

The “Pulitzer formula,” if there was one, was a story written so simply that anyone could read it, and so colorfully that no one would forget it. “The question, ‘Did you see that in theWorld?’” Pulitzer instructed his staff, “should be asked every day, and something should be designed to cause this.”

Not only did he have the temerity to dispatch his men to pester politicians, manufacturers, bankers, and society figures for answers to endless questions, he also instructed them to return with specific observations. Vagueness was a sin. A tall man stood six feet two inches. A beautiful woman had auburn hair, hazel eyes, and demure lips that occasionally turned upward in a coy smile.

Pulitzer had an uncanny ability to recognize news in what others ignored. He sent out reporters to mine the urban dramas his competitors consigned to their back pages. Typical, for instance, was the tale that ran on the World’s front page, soon after Pulitzer took over, about the destitute and widowed Margaret Graham. Dockworkers had seen her walking on the edge of a pier in the East River with an infant in her arms and a small child clutching her skirt. “All at once the famished mother clasped the feeble little girl round her waist and, tottering to the brink of the wharf, hurled both her starving young into the river as it whirled by. She stood for a moment on the edge of the stream. The children were too weak and spent to struggle or to cry. Their little helpless heads dotted the brown tide for an instant, then they sank out of sight.” Graham followed her children into the river, but she was saved by the onlookers and taken to jail to face murder charges.

In one stroke, Pulitzer simultaneously elevated the common man and took his spare change. He found readers where other newspaper publishers saw a threat.

Pulitzer pushed his writers to think like Charles Dickens, who wove fiction from sad tales of Victorian London, to create compelling entertainment from the drama of the modern city. In the Lower East Side’s notorious bars, called “black and tans” for the blend of stout and lager they served, or at dinner in cramped tenements, men and women did not discuss society news, cultural events, or happenings in the investment houses. Rather, the talk was about the toddler who fell to his death from a rooftop, the brutal beating police officers meted out to an unfortunate waif, or the rising fares of streetcar trips to the upper reaches of Fifth Avenue and the mansions where so many working people toiled as servants.

The World drew in these readers, many of whom were immigrants struggling to master their first words of English. Writing about the events that mattered in their lives in a way they could understand, Pulitzer’s World gave these New Yorkers a feeling of belonging and a sense of value. The moneyed class learned to pick up the World with trepidation. Each day brought a fresh assault on privilege.

In one stroke, Pulitzer simultaneously elevated the common man and took his spare change. He found readers where other newspaper publishers saw a threat. Immigrants were pouring into New York at an unprecedented rate. By the end of the decade, 80 percent of the city’s population was foreign born or of foreign parentage. Only the World seemed to consider the stories of this human tide deserving of news coverage.

Pulitzer’s own story would have been front-page material had he permitted it. Having arrived in the United States in 1864 as a penniless teenager who had been recruited as a mercenary for the Union army, Pulitzer gained his first perch as a reporter for a German-language daily newspaper in St. Louis by the time he was 20. Teaching himself English, he entered the hurly-burly world of immigrant politics under the wing of Carl Schurz, the prominent 19th-century German-American politician who served in the U.S. Senate and as secretary of the interior. Pulitzer served briefly as an elected state legislator and was a key member of the reform-minded Liberal Republican Party, a short-lived wing of the Republican Party that launched a failed insurgency against President Ulysses S. Grant. Afterward, Pulitzer became a lifelong Democrat.

Within a few years of arriving on Park Row, he had transformed theWorldinto the unquestionable ruling paper of the nation. Its power made it the 19th-century equivalent of CBS,The New York Times, and The Washington Post combined.

In his time, politics and journalism were two sides of the same coin. Out-of-work politicians became newspaper editors, and successful editors became elected politicians. In 1878, Pulitzer purchased The St. Louis Dispatch at a courthouse-steps bankruptcy auction, merged it with The Evening Post, and pioneered through experimentation the techniques that would make him a success in New York.

Within a few years of arriving on Park Row, he had transformed the World into the unquestionable ruling paper of the nation. Its power made it the 19th-century equivalent of CBS, The New York Times, and The Washington Post combined. (Every day, six acres of spruce trees were felled to keep up with the World’s demand for paper, and almost every day enough lead was melted into type to set an entire Bible into print.)

But Pulitzer’s motive for chasing readers was not simply pecuniary. He regarded journalism as a source of political power, the kind he had sought when he ran for office. He unabashedly used the paper as a handmaiden of reform, to raise social consciousness and promote a progressive—almost radical—political agenda, ranging from a tax on luxuries and large incomes to a crackdown on corrupt officials.

In his conception, this was the most important role of a newspaper. Reporting the news enabled him to build a readership that would turn to the editorial page for his own sage counsel on affairs of state and politics. “The World should be more powerful than the president,” Pulitzer once said. “He is fettered by partisanship and politicians and has only a four-year term. The paper goes on year after year and is absolutely free to tell the truth and perform every service that should be performed in the public interest.”

History tends to forget this lofty aspect of Pulitzer, because in pursuit of readers the World found itself locked in a no-holds-barred competition with The New York Journal, owned by William Randolph Hearst, an upstart imitator who had discovered that clamoring for war with Spain in 1898 boosted readership. The fight between the two sucked the newspapers into a spiraling descent of sensationalism, outright fabrications, and profligate spending that threatened to bankrupt both their credibility and their businesses.

“The World should be more powerful than the president,” Pulitzer once said. “He is fettered by partisanship and politicians and has only a four-year term. The paper goes on year after year and is absolutely free to tell the truth and perform every service that should be performed in the public interest.”

In the end, the two publishers survived this short but intense circulation war. But their rivalry became almost as famous as the Spanish-American War itself. Pulitzer was indissolubly linked with Hearst as a purveyor of yellow journalism. In fact, many later surmised that Pulitzer’s endowment of Columbia University’s journalism school and the establishment, at his death, of national prizes for journalists were thinly veiled attempts to cleanse his legacy. While the actions may have raised his historical standing, Pulitzer’s motives to improve the professionalism of journalism were heartfelt.

Aside from accumulating considerable political power, Pulitzer midwifed the birth of the modern mass media. He was the first media lord to recognize the vast social changes triggered by the Industrial Revolution, and to capitalize on them by harnessing the converging elements of mass entertainment and technological advances in printing and communication. In filling his newspapers with stories of human interest and sensation harvested from urban life, he radically changed the focus of the news by reporting on matters relating directly to his readers. Like many brilliant ideas, it is a notion that strikes one as common sense today but was radical in his time.

Pulitzer offered this wonder for a penny or two, a price almost anyone could afford. He made news into a commodity, as Ted Turner did a century later when he built CNN to cater to—and stimulate—viewers’ insatiable appetite for news (the same appetite that now drives readers to the Web).

For Pulitzer, journalism was a sacred pillar of democracy. Though he entered newspaper publishing with the goal of obtaining political power to further his reformist aims, over time he recognized that the craft in which he had met with such success had a higher calling. For that reason, when he outlined his plans for the Pulitzer Prizes at the end of his life, he included public service among the original journalism award categories.

Although he was at times an innovator in journalism, invention was not Pulitzer’s strength. Rather, he possessed remarkable foresight and had an uncanny ability to recognize value where others didn't. He was willing to take risks based on his insights when others remained timid.

For example, when evening papers were the weak sisters of morning editions, Pulitzer risked his last remaining savings on the Post-Dispatch. He was convinced that evening papers had a great future—and he was right. The advent of the telegraph and faster printing presses made it possible to publish an afternoon newspaper with news as fresh as that day, making morning papers look as if they were publishing yesterday’s news, which in fact they were. Urbanites, particularly factory workers and professionals heading home from work, had a voracious appetite for news and were primed to buy an evening paper. Gaslight, and subsequently electric light, also made reading the newspaper an important evening pastime. In a few years, evening newspapers outnumbered morning ones.

Pulitzer was halted before he had a chance to build a national chain of newspapers, as his younger rival Hearst would eventually do. In 1887, at age 40, he began to lose his eyesight; his deteriorating vision drove him into a personal purgatory of real and imagined illnesses, insomnia, and fanatical intolerance of all sound. The demons that beset him never rested until his death, after years of ill health, in 1911.

During his last two decades, he roamed the globe, living off the paper’s profits and his vast accumulated wealth. At any moment, he might be found consulting doctors in Germany, taking the waters in the south of France, resting on the Riviera, walking in a private garden in London, riding on Jekyll Island, hiding in his “Tower of Silence” (as he called a specially constructed turret at his Maine vacation home), or cruising aboard the Liberty, a luxurious private yacht rivaled in size and extravagance only by J. P. Morgan’s Corsair. At sea, the ship’s twin steam engines drove propellers set at different pitches and running at varying speeds in order to minimize vibrations carried through the hull. So engineered, the Liberty became, in effect, a seagoing counterpart to the Tower of Silence.

Throughout his long exile, Pulitzer never relaxed his grip on the World. A stream of telegrams, all written in a code of his own invention, flowed from ports and distant destinations to New York, directing every part of the paper’s operation, down to the typeface to be used in advertisements and the vacation schedules of editors. Managers shipped back reams of financial data, editorial reports, and espionage-style accounts of one another’s work. Although he had set foot in the skyscraper headquarters he built in 1890 on Park Row only three times, whenever anyone talked about the newspaper it was always “Pulitzer’s World.”

What would the founder of modern American journalism do today if he ran a newspaper, a product with fewer and fewer readers and of diminishing interest to advertisers? For one, he would sell its presses. The migration to the Web would be an unmistakable trend to a man with Pulitzer’s predictive sense. But he would probably be—as are today’s media lords—without a cure for the economic cancer eating away at the news media. In his day, the only way businesses could reach consumers was in print. The newspaper with the most readers held the key to the kingdom of profits because it offered the most efficient way for advertisers to make this connection. In those circumstances, it was easy for Pulitzer to tell his readers, when he reduced the price of his paper to a penny, “We prefer power to profits.”

But following that dictate today has put the members of the Graham, Ochs, and Sulzberger newspaper families in an intractable quandary. They are giving away their work on the Internet in order to retain their influence in an era in which they no longer offer the most viable venue for advertising. Pulitzer’s descendants saw the writing on the wall in 2005 and sold all their remaining media holdings, including his original St. Louis newspaper, while these assets could still fetch billions of dollars.

For Pulitzer, journalism was a sacred pillar of democracy. Though he entered newspaper publishing with the goal of obtaining political power to further his reformist aims, over time he recognized that the craft in which he had met with such success had a higher calling. For that reason, when he outlined his plans for the Pulitzer Prizes at the end of his life, he included public service among the original journalism award categories. “Our republic and its press will rise or fall together,” he said, in words that today are inscribed on the walls of Columbia’s journalism school. “An able, disinterested, public-spirited press, with trained intelligence to know the right and courage to do it, can preserve that public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery.”

* * *

James McGrath Morris is the author of Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power (2010). He edits the monthly newsletter Biographer's Craft.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons