Winter 2010

Tame Rebellion

– Michael Anderson

The 1950s are often perceived as a halcyon era of conformity, tradition, and sexual reticence, but a new book argues that anxieties surrounding the development of a "permissive society" were just as high then as they are now.

Has any decade of the American Century been written about more yet understood less than the Fifties? In both the popular and the scholarly minds, it exists as caricature, one held in contrast with an equally cartoonish conception of the Sixties: either a prison preceding liberation, or Eden before the Apocalypse. “When conservatives look back to the 1950s,” Alan Petigny writes, “they see an era of sexual reticence, a time when conservative Christianity was on the march, a halcyon era of order and tradition untarnished by the turmoil that would come. Conversely, liberals often vilify this time for its hypocrisy and repression.” More sensibly, scholars have recognized that one decade flowed into its successor, that the Fifties paved the way for the Sixties. Although Petigny would have it otherwise, The Permissive Society demonstrates the truth of the middle way.

Born from his doctoral dissertation, the book displays more bumptiousness than brilliance. American manners and mores “had been on the march for at least half a century,” he writes, and the pace accelerated ever more rapidly after World War II. This moment he portentously calls “the Permissive Turn”; it was, in fact, the final triumph of the social trend increasingly dominant since World War I (an event The Permissive Society ignores), urban modernism. Petigny essentially transposes contemporary culture wars back a half-century. What he approves of is “open and democratic,” not to mention “modern”; what he disdains are prejudices such as “elitism and sexual prudery.” The first, no surprise, is “liberal,” the second “conservative”—labels now so greasy that they would scarcely have utility even with the careful definition Petigny neglects to provide. A pity, because his hours in the stacks have yielded a profusion of data that might facilitate some genuine insight into a pivotal era.

Anyone middle-aged in 1950 had experienced three worldwide catastrophes—two world wars and an equally devastating economic collapse. Reconstruction was in order, for individuals as well as for society, and to replace the gods that had failed, Americans eagerly embraced ones that seemed more promising. As Petigny details, psychology was valorized: In 1955, the publishers of MAD magazine issued a new comic called Psychoanalysis; alcoholism was converted from a sin to a disease; and the clergy set about “transforming theology into therapy.” Religion itself substituted appeasement for apocalypse; Brotherhood Week “explicitly cautioned celebrants against engaging in discussions of theology or church policy,” and Dwight D. Eisenhower famously advocated “deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.”

Perhaps most tellingly, as described in Petigny’s best-argued chapter, the status of women was ever on the rise. They were no longer junior partners in marriage. “As Pat Boone crooned in his 1958 hit, marriage was now a ‘50-50 deal.’ ” A majority of Americans, both male and female, told pollsters they could endorse a woman as president, and “by the end of the 1950s, not only were there significantly more women serving as state legislators than at the end of World War II or at the close of the 1940s, but there were slightly more . . . than at the end of the 1960s.”

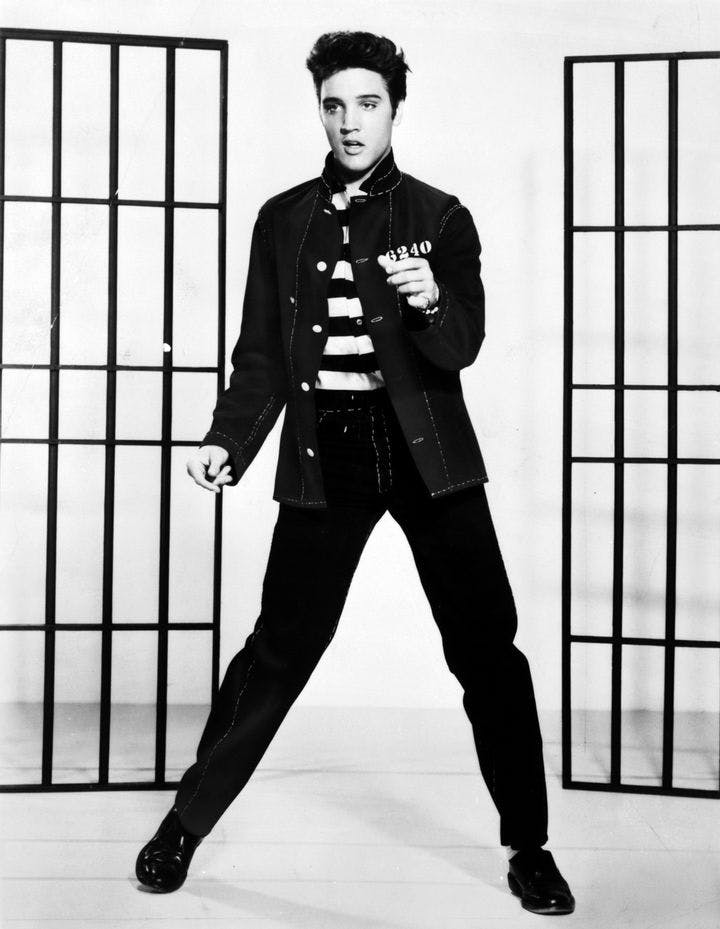

At the same time, however, Americans yearned for the simulacrum of stability. Indeed, a faux nostalgia for normalcy gripped the popular imagination, a desire to remember a world that never was. This was manifested most spectacularly in the Red Scare, but, perhaps not surprisingly, the urge to create an idealized past was visited particularly heavily upon the next generation. Despite the near-hysterical condemnations of their music (rock ‘n’ roll “often plunges men’s minds into degrading and immoral depths,” declared Martin Luther King Jr.), their clothes (a juvenile court judge cited blue jeans as “a factor in sex delinquency”), and their deportment (“Going steady is a menace to the purity of our youth,” the principal of a Roman Catholic high school proclaimed), Petigny perceptively notes that “the rebelliousness of teenagers was not only tolerated by the larger culture, but was, to a large degree, sanctioned.” No surprise: The “rebellion” was epitomized by the pranks of Dennis the Menace; the putatively defiant heroes of The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause wound up “affirming the ideals of the larger society.”

Uneasy, unsettled, traveling in competing directions, the unacknowledged act uneasily conjoined with the camouflaging word: This is the prescription for anxiety, the situation Sigmund Freud considered the besetting condition of modern man (not “guilt,” as Petigny writes). Little wonder that the decade saw the finest works from cinema’s master of psychological subversion, Alfred Hitchcock—the Fifties were indeed the Age of Anxiety.

* * *

Michael Anderson is writing a biography of the playwright Lorraine Hansberry.

Reviewed: "The Permissive Society: America, 1941-1965" by Alan Petigny, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons