Winter 2013

The case against blaming greedy bankers for the financial crisis

Inside the hidden roots of the financial crisis.

Don’t blame greedy bankers and hedge fund managers for everything that went wrong in the financial crisis of 2007–08. Decades of poorly conceived government policies set the stage by channeling money into consumer borrowing.

A crucial step, writes Louis Hyman, a historian at Cornell’s ILR School, was the creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) during the Great Depression. Previously, mortgage finance had been the domain of local banks, constrained by local resources. The new institutions tapped much larger sources of capital. The FHA insured mortgage loans, and Fannie Mae bought mortgages from banks and resold them to investors. Under the FHA’s Title I program, moreover, the agency insured small home-improvement loans to consumers. In 1935, lenders committed nearly a half billion dollars to loans for home improvements, an amount several times greater than the budget of the New Deal’s Public Works Administration.

All of these measures unlocked desperately needed capital and helped the economy, but there were other effects. Commercial banks in the past had been wary of lending to consumers; the new federal financial infrastructure encouraged the banks to dip their toes into that market. And to the degree they did they siphoned credit away from small and medium-sized businesses.

The real problems began in the 1960s, Hyman says, “as federal policymakers lost sight of how the economy was constructed by their policy.” Watching America’s suburbs flourish while its cities moldered, Congress wrongly concluded that easy credit (rather than good jobs) was responsible for the suburbs’ growth and set about trying to increase the flow of mortgage dollars. In the past, Fannie Mae had resold individual mortgages to investors, but on February 19, 1970, along with another institution, it issued the first mortgage-backed securities, packaging mortgages into bonds that had many more potential buyers. Again, the price was paid in reduced credit available to businesses.

In 1983 came another crucial federally sponsored financial innovation, the collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO). Now mortgage bonds were sliced into tranches, each with different interest rates and maturity dates. Investors loved them — so much so that financial institutions applied the idea to credit card debt, car loans, and many other forms of debt. The credit explosion was born.

In the past, Hyman says, banks and other mortgage lenders had asked themselves, “Can I sell this loan if I make it?” Now they asked, “How can I produce more loans for the market?” They flooded high-risk borrowers and redlined neighborhoods with aggressive loan offers, even as businesses in those same neighborhoods found loans hard to get.

Until 1970, Hyman concludes, a “virtuous system … balanced business and consumer debt.” The federal government had often used its power to steer credit into business investment, which led to the creation of high-paying jobs. “Even now, as we consider remedies to the financial crisis, we should be considering not just what the state can restrict but what it can do” to shape credit markets and help industry. “Personal debt,” Hyman reminds us, “is anything but individual.”

THE SOURCE: “The Politics of Consumer Debt: U.S. State Policy and the Rise of Investment in Consumer Credit, 1920–2008” by Louis Hyman. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Nov. 2012.

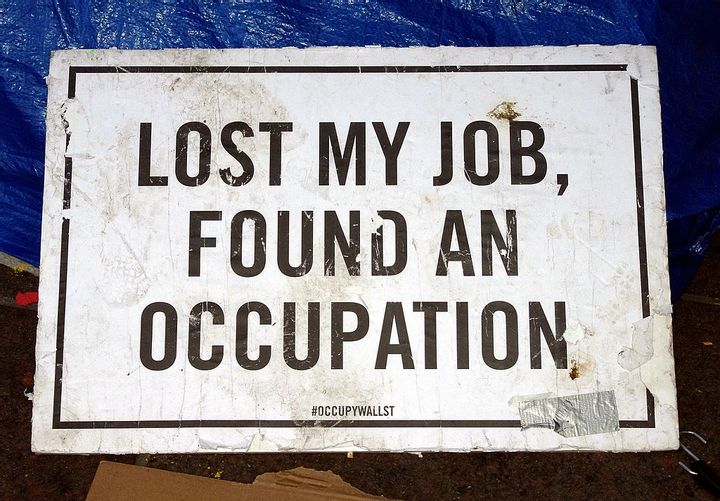

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons