Winter 2013

Is America’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ a bad idea?

– The Wilson Quarterly

In short, the pivot appears to be a dangerous flop.

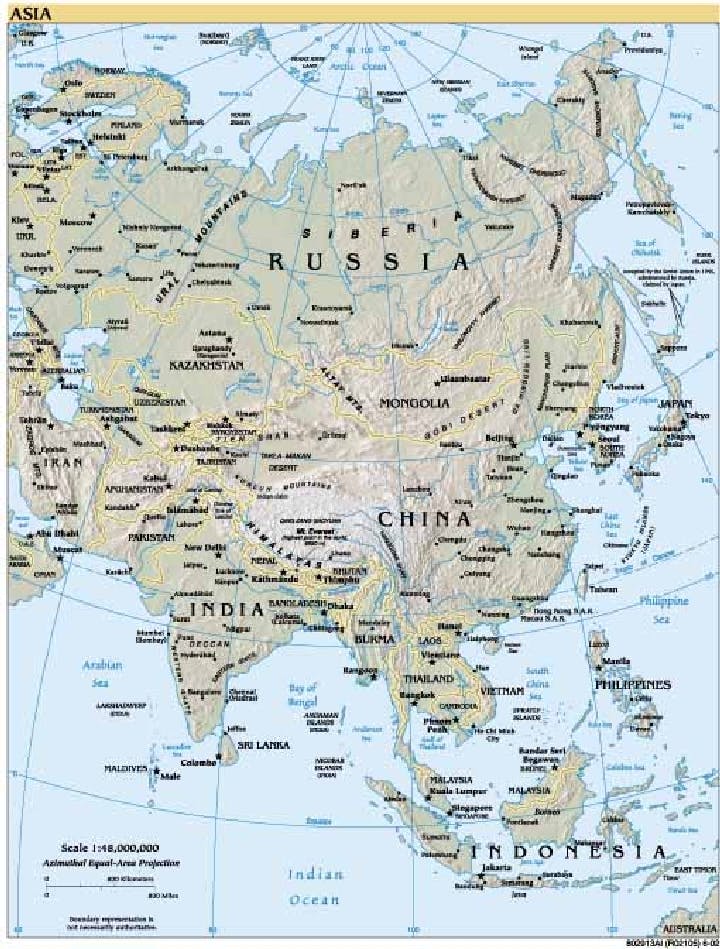

Many American grand strategists agree: Europe is slumbering and Asia is stirring. China is the great power the United States should keep an eye on. In 2010, the Obama administration announced a long-term “pivot” toward Asia, which involves, among other things, drawing down long-deployed military forces in Europe and inking defense deals and basing agreements with allies in East Asia.

The pivot will leave little in the realm of international affairs unaffected. America has been a sturdy presence in Europe for 70 years, stationing fleets of ships and hundreds of thousands of troops there. After the Vietnam War, it took the opposite approach in the Pacific, preferring a lighter touch of economic engagement and maritime dominance.

The sudden switch has gone little discussed amid a welter of more pressing concerns, from Iran to the domestic fiscal crisis. Now, however, a few foreign-policy specialists are weighing in.

Robert S. Ross, a political scientist at Boston College, thinks the pivot is a mistake. China has made more trouble than usual for the United States over the last few years, he admits. That’s not because it seeks conflict. Rather, the regime in Beijing is skittish. The global recession wreaked havoc on the Chinese economy and spurred social unrest. The communist regime could no longer buy popularity with spectacular economic growth. Instead, it resorted to “appeasing an increasingly nationalist public with symbolic gestures of force.”

Since 2010, Washington has responded to China’s new nerve by rekindling old friendships in the Pacific and bolstering defense ties with offshore nations such as New Zealand, Japan, and the Philippines. These moves were necessary, Ross says, and in some ways were consistent with a long-standing trend toward increased engagement in the region.

But Ross feels that the pivot has spun too far, citing China’s displeasure with Obama administration policies such as refurbishing ties between Seoul and Washington (which had weakened somewhat under George W. Bush) and expanding military cooperation with Cambodia and especially Vietnam, which borders China. In 2010, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton openly expressed support for the Philippines and Vietnam in their spat with China over the Spratly Islands — a break with the past U.S. policy of staying out of territorial disputes.

Beijing is livid. China halted cooperation with the West in dealing with belligerent states such as Iran and North Korea. Also, in 2012 China announced plans to drill for oil in disputed waters in the South China Sea, and it has taken steps to enhance its military capabilities there.

In short, the pivot appears to be a dangerous flop. “A strategy that was meant to check a rising China has sparked its combativeness and damaged its faith in cooperation,” Ross argues. Chinese leaders have concluded that the United States has abandoned its decades-old policy of strategic engagement.

Nor is it only America’s position in Asia that could suffer. Josef Joffe, editor of the German weekly Die Zeit and a professor of international politics at Stanford, warns that America’s turn away from Europe — greeted so far with “astounding” silence on both sides of the Atlantic—is an invitation to trouble.

It is true that Europe is no longer the world’s strategic fulcrum and that the Soviet threat is gone. The “core” of Europe is stable. But “the fringes are brittle,” Joffe says. If fighting breaks out in the Balkans, the former Soviet states, or nearby neighborhoods such as the Levant and North Africa, Europe will need much more than a few brigades of American soldiers to restore stability. (Only 30,000 U.S. troops remain in Europe, one tenth of the peak total during the Cold War.)

The fact is that the Europeans are not up to the job themselves. Except for France and Britain, the European states invest little in their militaries. Only with the help of the United States and the NATO alliance, which has “built a precious edifice of command and training,” can Europe accomplish much of anything militarily. France led a European charge into Libya in 2011, but the effort sputtered until the United States arrived with crucial surveillance technology, smart bombs, and know-how.

Yet for all their maddening feebleness, the Europeans are stauncher allies than other candidates — India, Australia, Saudi Arabia. Finally, Joffe argues, “Europe is simply closer to the theaters where the U.S. might need to fight tomorrow.” That’s important for more than one reason. “Forces in situ are even better for not having to fight; they are there for deterrence.”

Michael Wesley, a professor at the University of Sydney in Australia and a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution, warns that Americans must be more clear eyed about Asian realities.

The Asian order that predominated between 1975 and 2000, in which the United States presided over a regional system of alliances without a clear Asian leader, is vanishing, Wesley says. What he calls “hegemony lite” is history. China’s rise has awakened old tensions throughout Asia, stirred new conflicts, and pushed up military budgets as well as the level of belligerent rhetoric. For the United States, Asia is becoming a much more complicated place. Petty disputes between America’s friends in the region and Beijing, for example, “pose a never-ending dilemma over when to demonstrate commitment to allies and when to stay silent to keep China’s neighbors from becoming too assertive.”

Wesley recommends that the United States rise above the fray and let others in the area keep China in check. This, he argues, will “present China with a much more complicated challenge than direct military competition with the United States.”

Trade and regional integration also counterbalance China’s power. Asia’s prosperous powers increasingly rely on their neighbors to keep their economies growing. War would put a dent in everyone’s profits and cut off vital sources of raw materials. Promoting further economic integration in Asia would build a strong sense of shared interest.

What happens to Europe, then? Die Zeit editor Joffe accepts that some kind of picot to the Pacific is necessary, but not one in which America turns its back on Europe. “The Atlantic is home. Home is boring and exasperating, yet, in the words of Robert Frost, it is also the place ‘where they have to take you in.’”

THE SOURCES: “The Problem With the Pivot” by Robert S. Ross, Foreign Affairs, Nov.–Dec. 2012; “The Turn Away From Europe” by Josef Joffe, Commentary, Nov. 2012; “Asia’s New Age of Instability” by Michael Wesley, The National Interest, Nov.–Dec. 2012.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons