Winter 2020

Speech in a Low Dishonest Decade

– Lisa Marie Anderson

Universities tried to ban antifascist speakers in the 1930s. Madison Square Garden hosted U.S. Nazis. What can we learn from this history?

The current debate about controversial invited speakers on university campuses (or in other public spaces) asks us to hold multiple truths in our minds at once. Alongside the long and important tradition of protecting speech rights and academic freedom against censorship and intimidation, stand other traditions that have amplified the speech of the powerful at the direct expense of others.

The muddiness of the present moment never provides perfect clarity; but mere hindsight often leaves us with the impression of historical and moral inevitability. Take the 1930s, which poet W.H. Auden famously called a “low dishonest decade,” when the rise of European fascism brought tensions over free speech to American campuses and other public venues – including Madison Square Garden.

Historians like Stephen H. Norwood and Bradley W. Hart have made the case that many American colleges and universities legitimated the Nazi government and its views throughout the 1930s, even as anti-Semitism was fully in evidence in Germany, and also on the rise in the United States. Prominent fascists and Nazi propagandists were welcomed to campuses as speakers over the loud objection of some students and faculty in the 1930s, while in other cases, anti-fascist speakers were prevented from addressing academic audiences for reasons researchers are still untangling.

Among the most prominent attempts to deny a platform to an anti-fascist speaker occurred in New York City in April 1938, when the prominent exiled German playwright Ernst Toller was caught up in a controversy that prompted anxious media coverage about freedom of speech at Queens College – which had opened its doors only six months before. The Queens affair also presented a challenge to academic freedom, at the very time the concept as we know it today was being hammered out.

Reexamining how such controversies were handled, on the eve of a cataclysmic war, reminds us of the difficulties inherent in the interplay of speech, power, and authority within a democracy.

A Man of His Times

The Queens College controversy started with little fanfare. English professor Dwight Durling suggested including Toller in a symposium on “Social Drama” planned for April 8, 1938. Toller lived in New York at the time and was one of the world’s most prominent playwrights.

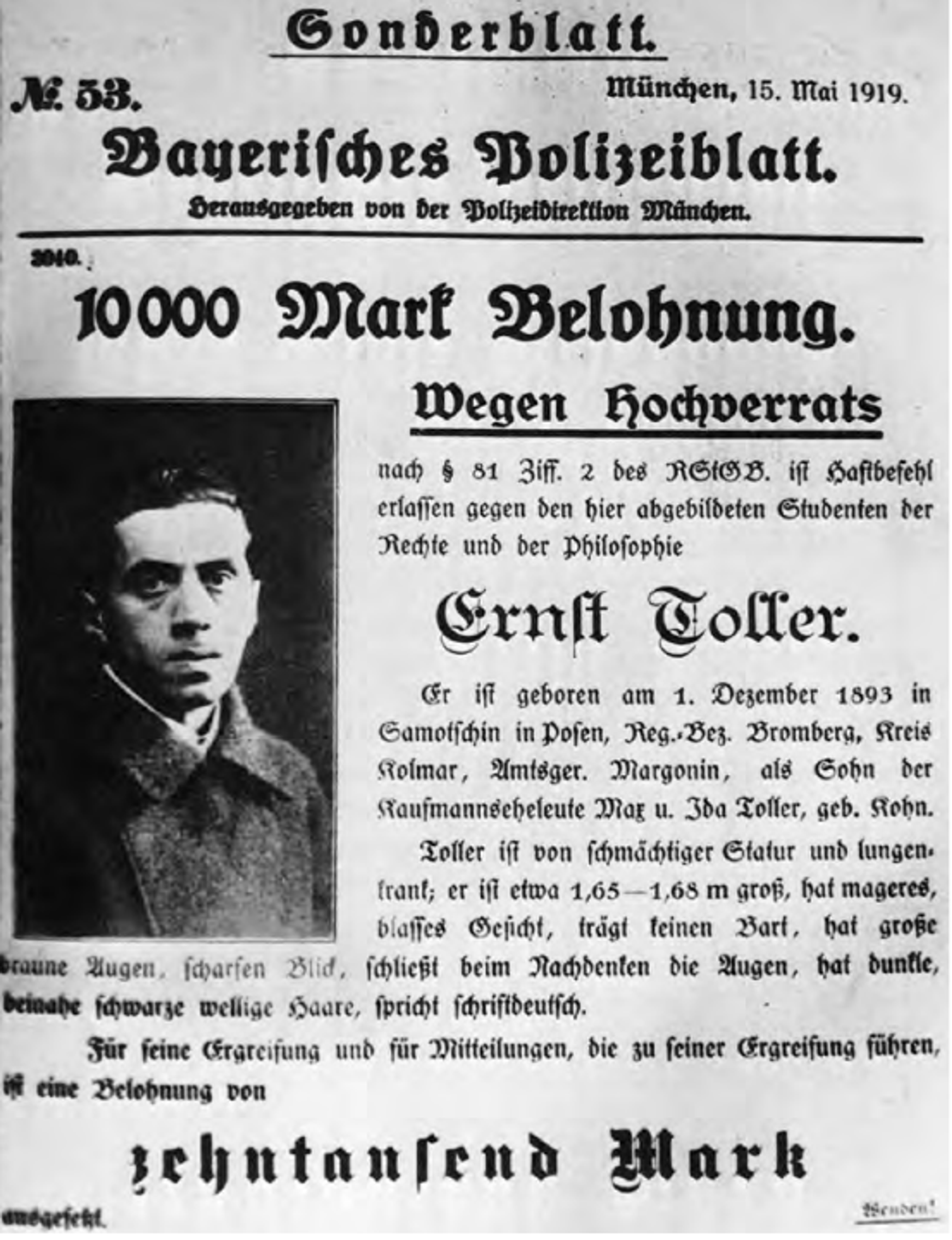

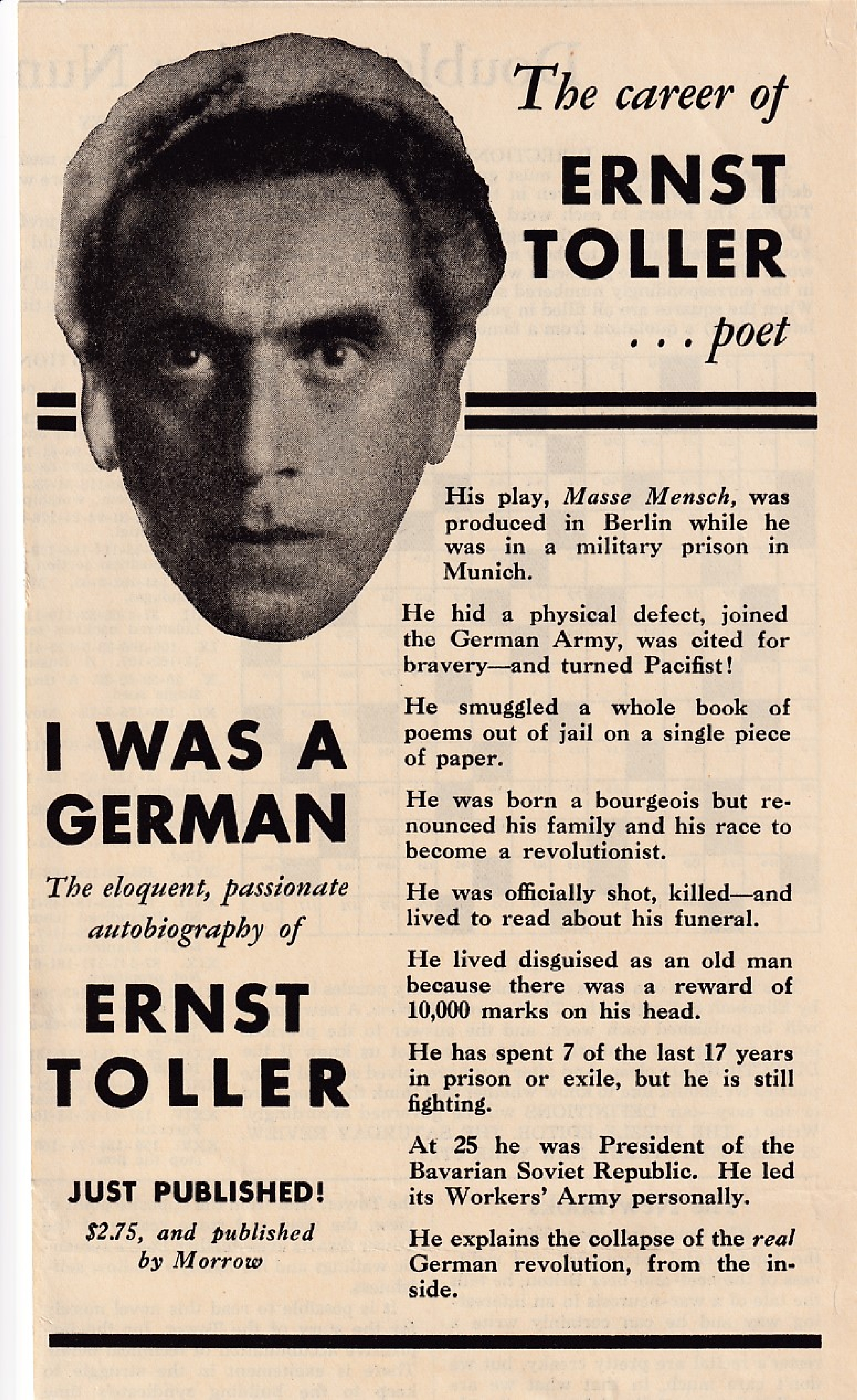

Born into a German-Jewish family in 1893, Toller’s university studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. His experience at the western front turned him into a pacifist and, eventually, a socialist activist. He was involved in Germany’s November Revolution (1918-1919) and briefly led the short-lived Workers’ Republic established by the revolutionaries in Munich.

Toller’s role in that government earned him a five-year sentence for high treason (handed down by the new government of the Weimar Republic). From his cell, he wrote plays that made him famous. His stage debut, Transformation, premiered to glowing reviews in September 1919, and was followed quickly by other masterworks of German Expressionism: Masses and Man, The Machine Wreckers, and Hinkemann.

Politically and stylistically provocative, Toller’s plays garnered as much controversy as praise. Masses and Man was criticized by some as too counterrevolutionary, by others as too bolshevist. (Toller never identified with communism and struggled against many of its ideologies.) When Hinkemann opened in Dresden in 1924, it was performed only once, due to an orchestrated reaction by Nazis who objected to its antiwar dialogue; fights broke out in the theater and the actors received death threats. Soon thereafter Nazis stormed a Vienna theater where the play was being performed, prompting the German Theater in Berlin to cancel plans to produce it.

“If the times betray the great ideas of humanity, it is the duty of the artist to outlaw the treachery, to deepen the feeling for freedom, justice, and beauty.”

Toller was a sought-after public speaker following his release from prison in 1924. The uncommon oratory talents that had served him during the revolution did so again as he spoke out against the hypocrisies of the Weimar Republic, imperialist wars, and the fascist ideas taking hold of Europe. The night after the Reichstag fire in February 1933, Toller’s apartment was raided; he was in Switzerland at the time and would never return to Germany.

In an April 1, 1933 speech announcing a boycott of Jewish businesses, Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels mentioned by name the “Jew Toller”; his books were soon burned in the infamous conflagration on Berlin’s Opernplatz. Toller went to London and completed the autobiographical book, A Youth in Germany. His exile later took him to the United States, where he traveled extensively, warning audiences about the spreading threat of fascism. Given the nature of his fame, he also continued to speak publicly about the theater and its role in free and just societies.

Invited or Not?

Two days after contacting Toller about the symposium, Durling called the playwright again to say Queens College would not be able to host him after all. Toller told the New York Times that the change was because the majority of the planning committee “felt that I was known internationally as an anti-Nazi, and because many students and constituents of the Borough of Queens were of first and second generation German extraction.” New York media reported that Toller was being prevented from speaking “for political and racial reasons.”

Durling and Queens College President Paul Klapper argued that Toller had not been disinvited because he had never been formally invited: Durling said he had merely made inquiries about Toller’s availability. But Klapper went further, telling The Brooklyn Daily Eagle that Toller was “not known to the New York theatergoer,” and was also “an ardent propagandist who might emphasize his special political philosophy to the exclusion of other aspects of the subject.”

A fierce backlash ensued. The New Theatre League wrote to Klapper: “we consider this discrimination against Mr. Toller as unwarranted, un-American and undemocratic. His lecture would have been but another demonstration of the fact that our traditions of freedom and tolerance are still valid.” John Gassner, a theater historian and critic who taught at Queens, declined to participate in the symposium in protest over the violation of Toller’s free speech rights. Broadway producer Brock Pemberton and dramatist Paul Vincent Carroll followed suit.

Soon implicated in the controversy was Queens Borough President George U. Harvey, a public official who had clashed previously with Klapper – and had a reputation as a defender of right wing groups. Klapper was a dean at Manhattan’s City College (a school with a liberal reputation) before being named as the first president of Queens College in 1937. His appointment led Harvey to threaten to close the new school upon “any evidence of communism” there, as opposed to “the patriotic teaching of subjects like history and economics.”

“The idea of denying our platform to a person who holds anti-Nazi views is too preposterous to be entertained.”

Klapper’s reassurances to Harvey in the press did not quell the Queens Borough president’s ire for long. Later that year, Harvey stormed out of the dedication ceremony for the new college, claiming that being given a less than prominent seat on the platform was retaliation for his insistence that “Queens men” be appointed at the new college, rather than Manhattan imports like Klapper.

Local politics was not the only spoon stirring the pot. In 1938, Harvey tried to found an anti-Communist organization that would influence teaching in local schools. He also came to be known as a defender of the Christian Front, which was linked with the German American Bund – an organization for Nazi sympathizers with a headquarters in New York City’s Yorkville neighborhood as well as youth and training camps around the region.

The New York Teachers Union blamed Harvey in its statement on the Toller controversy: “We have looked to President Klapper as a man of liberal mind who is doing much to promote democratic procedures in university organization. We are therefore surprised to learn that [he] has preferred to yield to the subversive fascist groups that cluster around Borough President Harvey…”

The New York Post also weighed in with a short editorial called “The Efficacy of Hush-Hush Tactics,” which emphasized that only Nazi sympathizers were likely to be offended by Toller’s views, “because, certainly, liberal or Catholic or Jewish or Masonic or strongly Protestant German-Americans are not sympathetic with the Nazis who have clamped down on all these groups in the homeland.” The Post also recounted an incident in Germany just months before Hitler came to power, when a radio speech Toller was scheduled to give was cancelled. The radio station supervisor who invited Toller had been held, for five years and counting, in a concentration camp.

“We hope,” the editorial concluded, “the incident registers on the authorities at Queens College.”

Indeed, the swirl of attention made an impression. Klapper finally agreed to welcome Toller to Queens College, calling the controversy “an unfortunate misunderstanding,” and saying that “no suspicion of intolerance or any intent to restrict civil rights – however unfounded its basis may be – shall ever be associated with Queens College.” Klapper added that “the idea of denying our platform to a person who holds anti-Nazi views is too preposterous to be entertained.”

Yet Klapper did muddy the victory for free speech. He stood by his earlier statements questioning whether an invitation to Toller had ever been made, and once again articulated his preference for “a speaker with a more eclectic outlook….”

On April 8, Toller joined Pemberton, Carroll and Gassner to address a crowd of more than 450 people at the symposium. Toller’s lecture traced the social content of drama across more than two millennia and argued for the moral as well as the aesthetic character of art. The playwright also spoke of a theater that served international rather than national interests, and that supported peace and understanding rather than war and racial hatred.

“If the times betray the great ideas of humanity,” Toller said, “it is the duty of the artist to outlaw the treachery, to deepen the feeling for freedom, justice, and beauty.”

Toller's story had a tragic end. Little more than a year later, amidst a confluence of personal and professional woes that played out against a darkening global atmosphere, the playwright committed suicide in New York City’s Mayflower Hotel on May 22, 1939.

Fascists at the Garden

The year after the Queens College affair, and just months before Toller’s death by suicide, New York City faced the question of whether the pro-Nazi German-American Bund should be given Madison Square Garden as a platform for a mass meeting.

Ultimately, a “Pro-American Rally” organized by the Bund to celebrate George Washington’s birthday was held at the venue on February 20, 1939. Twenty thousand people attended. They recited the Pledge of Allegiance to the US flag in the shadow of a banner depicting Washington, gave Hitler salutes, and raised banners marked with swastikas.

Bund leader Fritz Kuhn, who had moved from Germany to the US in 1927 and lived in Queens in the mid-1930s, gave a speech that night about the need for white-Gentile rule in the United States. He also lambasted the Jewish-controlled press and Jewish-Moscow domination.

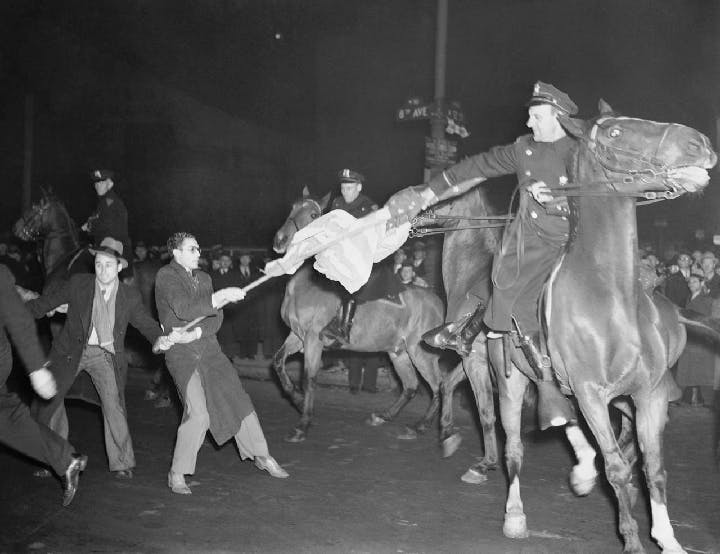

Kuhn’s speech was interrupted when a 26-year-old Brooklynite named Isadore Greenbaum rushed the stage. He was beaten up and removed to raucous cheers from the crowd. There was violence outside the arena, as well, with fights between the rallygoers, an estimated 100,000 protestors, and nearly 2,000 police officers.

The New York Times reported that the American Fund for Political Prisoners and Refugees came to City Hall with complaints that “anti-Fascists who were doing nothing but exercising their constitutional right of picketing the meeting in a peaceful fashion were ridden down and trampled by mounted police and brutally beaten by uniformed and plainclothes policemen.”

Recently, the Bund rally reemerged into discussions of free speech through the Oscar-nominated 2018 documentary, A Night at the Garden. Director Marshall Curry says that his initial interest in excavating footage of the event sharpened when American Nazis returned to the headlines after the August 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“When Charlottesville happened,” said Curry, “[the film] began to feel urgent.”

The questions that vex universities and municipalities today were just as alive in 1939. There were demands that the Bund rally be banned. New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and others believed that although the Bund was anti-Semitic and anti-democratic, the city’s issuance of a permit demonstrated the critical difference between the U.S. and fascist Germany. Even detestable individuals and groups must be allowed to express their opinions – and make themselves look ridiculous in the process.

Other voices countered that while this argument had merit, Madison Square Garden should not be transformed into a platform for hatred. Journalist Dorothy Thompson attended the rally and was escorted to an exit because she was laughing so loudly. She told the New York Times: “I laughed because I wanted to demonstrate how perfectly absurd all this defense of ‘free speech’ is in connection with movements and organizations like this one.”

Lessons Learned?

Today, as in the 1930s, invitations, disinvitations (and sometimes re-invitations) make for controversy and bad publicity at universities and in other public venues. And in many cases, the specific goal of the speaker is to excite such confrontations in the first place.

In an effort to nip the issue in the bud, University of Chicago Dean of Students John Ellison informed incoming students in an August 2016 welcome letter that (among other measures to defend academic freedom) invitations to speakers would not be rescinded because of controversial topics.

Michael S. Roth, President of Wesleyan University, issued a public response to the Chicago letter amidst the considerable media attention it received. Roth wrote: “When we make a subject part of a debate, we legitimate it in ways that may harm individuals and the educational enterprise. We must beware of the rubric of protecting speech being used as a fig leaf for intimidating those with less power.”

.jpg)

The Toller controversy at Queens College offers an important corollary to Roth’s advisory: institutions should be wary also of the rubric of protecting people from speech. They should do so not (only) for the reasons commonly argued by classical liberalism, but because such “protection” too is sometimes used as a fig leaf.

The decision to disinvite Toller was carried out in the name of the faculty and students of Queens College and the residents of the borough, lest they be offended by Toller’s supposedly anti-German views, or corrupted by his “propaganda.” But the impetus for the action was not from Queens students protesting the presence of a propagandist on their campus. It was issued by the college’s administration, in the context of ongoing outside political pressure.

The risks of violence arising from controversial speech are real – as demonstrated by the Bund’s Madison Square Garden rally in 1939 and the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, at which counter-protester Heather Heyer was murdered by a white supremacist and dozens more were injured. Those who asked that the Bund not receive a permit for Madison Square Garden, and many of those who protested there when they did, were concerned about the prevention of violence – not only on that night, but also in the future.

"We must beware of the rubric of protecting speech being used as a fig leaf for intimidating those with less power.”

When Isadore Greenbaum was arraigned for disorderly conduct for rushing the stage during Fritz Kuhn’s speech, the magistrate asked him: “Don’t you realize that innocent people might have been killed?” He responded: “Do you realize that plenty of Jewish people might be killed with their persecution up there?”

When our primary aim is to avoid offense or controversy – whether by allowing people to speak publicly or by preventing them from doing so – power relations are usually obscured and upheld rather than exposed and subject to critique. Yet such exposure and critique are precisely what many of today’s student activists are seeking in an era when, as Michael Roth put it, “violent racism has been exposed as a systematic part of law enforcement [and] the legitimation of hatred in public discourse has become an accepted part of national presidential politics…”

What seems most critical is that all the stakeholders in debates over speech at universities and elsewhere are held to a standard of honesty and frankness about what (and whom) they are protecting, and from what.

Lisa Marie Anderson is Professor and Chair of German at Hunter College, City University of New York. She is co-editing a new English translation of Ernst Toller’s autobiography.

Cover Photograph: A New York City mounted policeman outside Madison Square Garden during a German American Bund meeting attempts to take an American flag away from one of the demonstrators who marched outside on February 20, 1939. (Associated Press)