Fall 2014

Rise of the Post-Khomeini Era

– Haleh Esfandiari

1989 was a watershed year in Iran: constitutional changes, a fatwa against Rushdie, reconstruction from the Iran-Iraq War, and the death of Ayatollah Khomeini.

1989 was a watershed year in the history of the Islamic Republic: Iran’s leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued his fatwa (in effect, a death sentence) against novelist Salman Rushdie, rupturing relations between Iran and the countries of the European community; the destructive eight-year Iran-Iraq War was over, and post-war reconstruction could begin; and in anticipation of Khomeini’s death, the constitution was revised, concentrating even more power in the hands of the supreme leader.

Khomeini’s death removed from the scene the towering figure of the Islamic revolution — the man who had dominated and shaped Iran for the entire decade — and allowed a transition to a new team that would take Iran in a different direction, although the Khomeini legacy remained very much alive. The Iran-Iraq war, which had preoccupied Iran for eight years at enormous human and material cost, had ended in July 1988. The reconstruction of destroyed cities and infrastructure, job creation, and trade revival were immediate priorities.

Those who advocated engaging with the West, inviting foreign investment, and increasing private sector freedom stood against those who advocated economic autarchy, self-reliance, and state control of the economy. The former, led by then-parliament Speaker Ali-Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, won the debate. Rafsanjani began the difficult task of repairing Iran’s relations with the international community, and resumed diplomatic relations with England and France, among others.

Months of international fence-building were wrecked when Ayatollah Khomeini declared Salman Rushdie — whose novel, The Satanic Verses, he considered insulting to the Prophet of Islam — an apostate, and called on Muslims to kill him. Khomeini’s fatwa caused an international uproar, forced Rushdie into hiding, seriously disrupted Iran’s relations with the West, and led to the withdrawal of all EU ambassadors from Tehran. It wasn’t until 1998 that the costly crisis was brought to an end with a formal declaration by Iran’s new president, Mohammad Khatami, that the Iranian government had no intention of carrying out Khomeini’s fatwa.

Khomeini died in June 1989. Millions had deliriously greeted him when he returned from exile to Iran in February 1979, the triumphant leader of a successful Islamic revolution. Millions more mourned him when he died — the frenzied crowd tearing at his funeral shroud as his body was led through the streets of the capital. For 10 years, he had totally dominated Iran — his global prominence leading Time magazine to name him “Man of the Year” for 1979. He was the inspiration of a new constitution that established Iran as a quasi-theocracy, required legislation to be based on the shari’a (Islamic law), privileged the clergy as a ruling class, and vested supreme power in his own hands as the leading marja’, or Shi’ite “source of emulation,” of his time.

He presided over purges, trials, and executions — first of the ruling elite under the monarchy, then of the members of left-wing and liberal political movements, intellectuals, and traditionalists who opposed or simply disagreed with his policies. He even turned his wrath against highly respected senior clerics, his own comrades-in-arms, who articulated a vision for Iran different from his own. These included his chosen heir-apparent, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, who had dared challenge the excesses of the regime.

Khomeini condoned the taking of American hostages at the U.S. embassy in Tehran in November of 1979, and finally approved their release 444 days later. When Iraq attacked Iran in 1980, he helped mobilize the entire country to fight the aggression. Determined to punish Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein — and, perhaps, to see an Islamic government established in Baghdad — he refused to end the war when Iraqi troops were expelled from Iranian soil in 1982, and instead carried the war into Iraqi territory. Six years and half-a-million Iranians dead and maimed later, when the tides of war again turned in Iraq’s favor, the Ayatollah declared his readiness to “drink the bitter chalice of poison,” and accepted a ceasefire with the Iraqi enemy.

Much of what he put in place survived him — most obviously, the unique institutions of the Islamic Republic. He was a prime proponent of exporting the revolution (as have been his successors, although they chose different ways of doing so). He hated monarchies — not only Iran’s, but also the kingdoms of the Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, Morocco, and Jordan. He left a legacy of deep mistrust of the United States (which he identified as a supporter of the Shah and the exporter of an alien, intrusive culture), but also of the Soviet Union (another great power, and a godless one at that). He once advised Soviet Leader Mikhael Gorbachev to enlighten himself by studying the great thinkers of Islam. He was not easily crossed. He welcomed to Iran and publicly embraced the PLO leader, Yasser Arafat, shortly after the revolution, but cut him off completely when Arafat did not condemn the Iraqi aggression against Iran in 1980.

Before Khomeini’s death (and with his approval), his lieutenants began to prepare for succession into a post-Khomeini era. In April 1989, Khomeini appointed a 20-man assembly to revise the constitution. The assembly, whose work was completed only after Khomeini’s death, amended the constitution in important ways. The post of prime minister was abolished, and his powers were vested in the office of the president. Judicial authority was vested in a single individual, rather than the council of five jurists under the 1980 constitution; this head of the judiciary was given the authority to appoint all senior judicial officials. Direction of the national radio and television broadcasting services was transferred from a three-man council (representing the three branches of government) to a single individual appointed by the Supreme Leader. A new Supreme National Security Council — headed by the president, and including representatives from the foreign ministry, military, and security services — was created to deal with matters of internal and external security (in subsequent years, the Council played an important role in the security and foreign policy sphere). Power was centralized, and clerical domination of Iran was strengthened.

Significant amendments were also made regarding the office of the supreme leader, or faqih, a post thus far held only by Khomeini. The original constitution envisioned that after Khomeini, supreme leadership could be exercised by one man — or, if a sufficiently eminent jurist could not be found, by a council of three jurists; the amended constitution saw to it that only one individual could hold the office. In addition to the extensive powers already vested in the supreme leader, the faqih was now given the authority to set the overarching policies of the Islamic Republic — to decide, in the words of the new constitution, issues “which cannot be resolved in ordinary ways.” This vague formulation gave the faqih the power to intervene and decide major political questions that were subject to dispute among the branches of government or within the political class. To advise the supreme leader on matters of policy and arbitrate disagreements between the parliament and the Council of Guardians (a constitutional watchdog body), a new institution was formed: the “Expediency Council,” its members appointed at the faqih’s sole discretion.

At the same time, in a carefully managed arrangement, the qualifications of the supreme leader were downgraded to allow for the post to devolve not to one of the leading Islamic jurists of the time (the most qualified were not sympathetic to the vision for Iran of Khomeini or his lieutenants), but instead to a cleric of lesser scholarly standing: Ali Khamenei, a mid-ranking cleric and member of the inner circle. The proposed constitutional amendments were approved in a national referendum in July — the same month that Hashemi-Rafsanjani was elected the first post-Khomeini president, bringing to the presidency a man of decidedly pragmatic inclinations.

1989 thus marks the beginning of Iran’s post-Khomeini era, when his lieutenants were free (or at least freer) to chart their own course; the start of the two-term, eight-year Rafsanjani presidency, marked by more pragmatic, but also more ambitious, policies abroad; an easing of domestic social and cultural controls; and greater economic freedom for the private sector.

In the 25 years since Khomeini’s death, competition between three strains in political ideology — conservative, moderate pragmatist, and sweeping reformist — has characterized Iran’s politics, with conservatives still dominant in the centers of power. President Rafsanjani would go on to lay the groundwork for the major reform movement that emerged under President Khatami in 1997. Both Rafsanjani and Khatami were ultimately frustrated in their endeavors.

The Khomeini legacy — inherited by those whom analysts call ‘conservatives’ and ‘hardliners’ — and the revolutionary spirit he embodies, proved too strong.

* * *

Haleh Esfandiari is the Director of the Middle East Program at the Wilson Center.

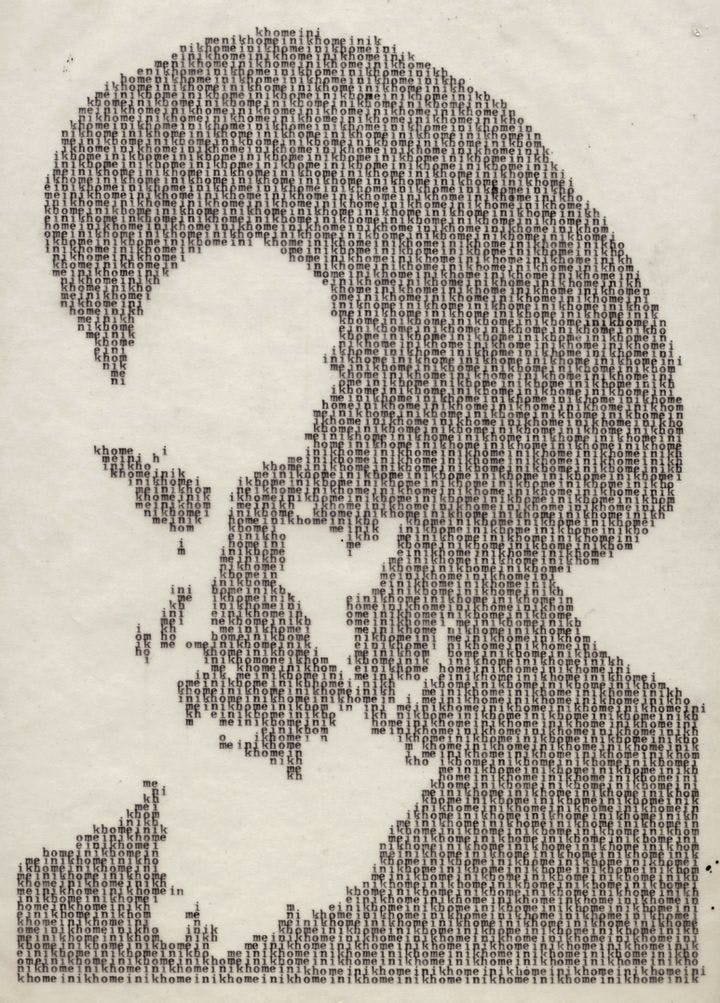

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Neil Hester