Summer 2024

The Case for International Migration

– Jack A. Goldstone

Expanding avenues for legal migration helps to meet vital demographic needs in destination countries while also benefiting homelands.

International migration is one of the most controversial issues for policymakers worldwide. Yet data show that global migration provides unequivocal economic benefits to receiving and sending countries, and to the migrants, with few if any of the cultural, criminal, or other alleged costs often cited against it.

For decades, economists searched for evidence that immigrants harm the economy, either depressing wages for native-born workers or draining public finances. Yet the results of rigorous investigations consistently find positive effects, with immigration leading to major economic benefits. For example, the United States’ bipartisan Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, recently sought to explain why America had by far the strongest recovery from the COVID-induced recession of any other developed country, with faster overall growth, lower unemployment, less inflation, and faster wage growth than other high-income nations. The CBO credits immigration for America’s success. A slow-down in immigration during 2020-2021 depressed the US labor force by about 2 million workers compared to what would have been the case with normal levels of immigration. Since then, immigration has rebounded. The CBO estimates that the rapid recovery of immigration accelerated the economy, increasing growth by 70,000 jobs per month in 2022 and 100,000 jobs per month from January 2023 to July 2024. The study also found that wage growth was even faster in immigrant-intensive industries than in others.

In just the next 25 years, the leading industrial powers are thus projected to lose a large portion of their prime-age labor force, and the loss is virtually global.

Looking ahead, the CBO predicts that US GDP will be $7 trillion higher over the next decade than would have been the case without the increase in immigration. That boost will also result in an additional $1 trillion in revenues for the US government.

Aside from economic issues, immigration is also often falsely linked to crime. Despite increased immigration to the US in recent years, crimes are significantly down by every measure. In fact, immigration and crime have moved in exactly opposite directions: From 1990 to 2022, the number of immigrants residing in the US more than doubled, from 19.8 to 46.2 million, and are now 14% of the total population, up from 8%. As the immigrant population has grown, violent and property crime rates in America have plunged. FBI data and victimization surveys show that violent crimes fell by more than half from 1993 to 2022, and that property crimes fell by two-thirds. Furthermore, numerous studies of the arrest rates of immigrants (compared to native-born Americans) confirm that immigrants commit fewer crimes. One Stanford University study found that since the 1960s, immigrants in the US have been incarcerated at rates 30% to 60% lower than those born in America.

The Future is Coming: Population Change and the Need for Migration

While immigration is not harmful, do we need it? A major factor are the labor needs of developed countries, whose populations are now aging and shrinking more rapidly than at any time in history. Unlike the recent past, in the future most countries, even in peace and good health, will experience a steady decline in their populations, and especially those of working age. That is wholly new.

Table 1 below, based on the World Population Prospects 2024, shows the expected decline in the prime working-age population (age 15-49) in the next 25 years in the major industrial countries.

In just the next 25 years, the leading industrial powers are thus projected to lose a large portion of their prime-age labor force, and the loss is virtually global. Even India, where births peaked in 2001 and have been declining by about 300,000 per year since, is experiencing marked population aging, with three-quarters of its projected population increase resulting from people living longer and not having more children. Only the US, among the countries in this chart, matches India by keeping a roughly constant number of prime age workers, and there, the projection is entirely dependent on maintaining the current net migration level of more than 1 million immigrants per year.

In the long run, most countries hope they will be able to stabilize their populations—or shift to a slow and manageable decline. However, in the short term, immigration will be essential to keep their economies running and help governments pay the costs of pensions, healthcare, and defense. The one area of the world where young workers seeking education and employment are plentiful is Africa, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa, likely to see a near doubling of its 15-49-year-old population, reaching more than 1.1 billion in 2050. Given the coming shortfall in workers in low- and middle-income countries, it will be imperative that African youth are able to contribute to the global economy to avoid a staggering slowdown in economic growth. Much of that will be a matter of Africans building the economies within Africa, but to a considerable degree, the world’s economy will also depend on African youth working in the aging and shrinking higher-income countries.

The Surge Factor

If immigration is economically beneficial and associated with lower rates of crime, why is there hostility toward it both in Europe and the US? The reality is that the degree to which people say that immigration is a critical problem varies greatly over time. In 2024, Americans cited immigration as their number one concern for the country, yet it has not always been near the top. Since Gallup began regular polling on this issue, immigration has been cited as the most important problem facing the country by an average of just 6% of Americans. The data show that the fraction of Americans polled citing immigration as the most important problem is generally low, but spiked in 2006-2008, in 2014, in 2018-19, and again in 2024. Each of these spikes was the result of a surge in certain kinds of immigration that captured popular attention.

In 2000-2006, following Hurricane Mitch and a surge in migration from Central America, apprehensions at the US Southern border shot up to more than a million per year. But during 2007 to 2018, apprehensions fell and stabilized at about 300,000 to 400,000 per year. Public concerns about immigration dropped dramatically, spiking only once (in 2014) when coverage of a new phenomenon—young immigrants, often unaccompanied minors, crossing the border—garnered interest. Then, in 2018-19, large numbers of families began crossing the border (total apprehensions doubled to more than 800,000 in fiscal 2019) and President Trump’s new policy of separating children from their parents sparked attention and controversy. Finally, from 2022-2024, when apprehensions at the Southern border soared to a record-breaking pace driven by pent-up demand after a decline during COVID, the scenes of masses of immigrants awaiting processing pushed concern back to the top.

A similar pattern is evident in the United Kingdom: Concerns over immigration spiked sharply in 2015-2016 following the mass migration to Europe of refugees from the civil wars in Afghanistan and Syria. This surge helped backers of the UK’s EU Referendum win support for Brexit. But after 2016, according to British journalist John Burn-Murdoch, “the number of people saying that immigration was one of the top issues just fell off a cliff. It went from sort of 45 percent to 10 percent at the same time as the actual numbers of immigration were rising.”

Today, the US receives more migrants from Asia and Africa than from Mexico, a pattern that will likely continue while their populations remain much younger than that of the US.

Why do spikes in immigration have such a large impact on attitudes toward immigration? It is not because they change the perception of immigrants or immigration as such. Americans have generally said that immigration is good for the country and continue to do so. Gallup polls have found those who say immigration “is a good thing for this country” was as high as 77% in 2020 and was still a large majority at 64% in June of 2024. What Americans strongly oppose is chaotic or “out of control” immigration. As Burn-Murdoch states, “generally speaking, whether we’re looking at the US, the UK, or Europe, the concern that people have is not with people coming to work in the country; it’s not with people coming to study in the country. It’s a concern with people who are arriving in the country without any clear pathway into society, as it were, and this general sense that there is a lack of control over what’s happening.”

Surges of migrants—picture crowds gathered at the borders and spilling out of detention centers—and reports of border authorities and resettlement agencies being overwhelmed convey precisely that sense of lack of control. People want to feel secure behind their borders and that immigrants are being properly vetted and processed by the authorities. Chaos at the border strips away that sense of security. But surges of migrants need not cause chaos. For example, in 2023, the US implemented a new process for migrants to legally enter the US in response to the crisis at Mexico’s Southern border. 2022 had been marked by tens of thousands of Venezuelans, Cubans, and Nicaraguans showing up at the Mexican border to seek asylum. In response, the US Department of Homeland Security developed a lawful process by which residents of these countries who have a supporter in the US, clear security vetting, and meet other eligibility criteria, can obtain a temporary residence and work authorization online and then legally travel to the United States. Since these measures took effect, the number of unlawful encounters at the Southwest border involving migrants from those countries has dropped by almost 90%. Similarly, when Europe faced a surge of asylum seekers fleeing the war in Ukraine in 2022, European Union authorities quickly enacted measures to give Ukrainian citizens permission to live, work, and study in the EU for up to three years. These measures facilitated the rapid and orderly processing of more than 3 million Ukrainian migrants. These programs show that legal and orderly pathways can be created to facilitate immigration without chaos or confusion.

Migration “Superpowers” are Leading the Way

While countries around the world are rethinking immigration to deal with their shrinking and aging populations, they can learn lessons from what I refer to as immigration superpowers: countries that managed to thrive with foreign-born populations exceeding 20% of their total populations. These countries are among the richest nations in the world; they have thrived precisely by welcoming talent from across the globe.

These countries have benefitted from treating the entry and absorption of immigrants not as a problem to avoid, but a pathway to growth. They set up sufficient administrative capacity to identify and vet immigrants and devoted sufficient funds to integrate them, and are thriving with levels of foreign-born populations up to twice that of the US or most other European nations.

A Future of Win-Win-Win

Fighting against immigration—in a world where the largest economies are facing a rapid decline of workers—is a futile and self-defeating path. The most successful economies are and continue to be the countries that are most capable of attracting global talent and integrating foreign workers. What’s crucial is not just the ability to recruit and absorb workers, but also having the capacity and administrative means to cope with surges of immigration in an orderly, legal, and secure manner. The inability to deal with migrant surges will discredit immigration—arousing fears and driving policies that leave countries less able to compete.

There are great benefits in a future world of increased orderly and law-abiding international migration. First, expanding the avenues for legal migration meets the need for labor in destination countries by reducing the flow of illegal migration and removing migrants from the clutches of human smugglers. Second, migrants send home remittances that can help feed, house, and educate people in their home countries. Third, migrants who gain skills, savings, and experience working abroad often return home to start companies and employ people in their homeland, thus relieving the pressure for future migration. A cycle that begins with increased migration to serve the labor needs of the destination country ends with reduced migration and increased economic development for the sending country.

This cycle has already played out between the United States and Mexico. While the majority of migrants to the US in the late 20th century were from Mexico, Mexico’s economic development during that period led to a sharp fall in fertility and a decline in migration to the point that by 2015, the flow of Mexicans to the US had turned negative, with more Mexican-born individuals leaving the US than entering. Today, the US receives more migrants from Asia and Africa than from Mexico, a pattern that will likely continue while their populations remain much younger than that of the US. Still, the cycle will eventually turn for them as well. Properly scaled up and regulated, international migration is a win for destination countries, for the migrants themselves, and for their home countries.

The UN has already gathered nations to craft a global compact for “Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration” that was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2018. While this compact provides a path to more orderly international migration, adopting its model remains voluntary. What stands in the way of compliance are the efforts of many national leaders to elicit anti-immigrant feeling in pursuit of their own political agenda. Yet the changing realities of countries’ populations and age structures will soon force leaders to face the need for immigration to sustain their nations’ economic growth and competitive standing. Expanding legal and orderly migration offers benefits that are now too vital and too large to ignore.

Jack A. Goldstone, PhD, is the Virginia E. and John T. Hazel, Jr. Professor of Public Policy, George Mason University and a global fellow with the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program.

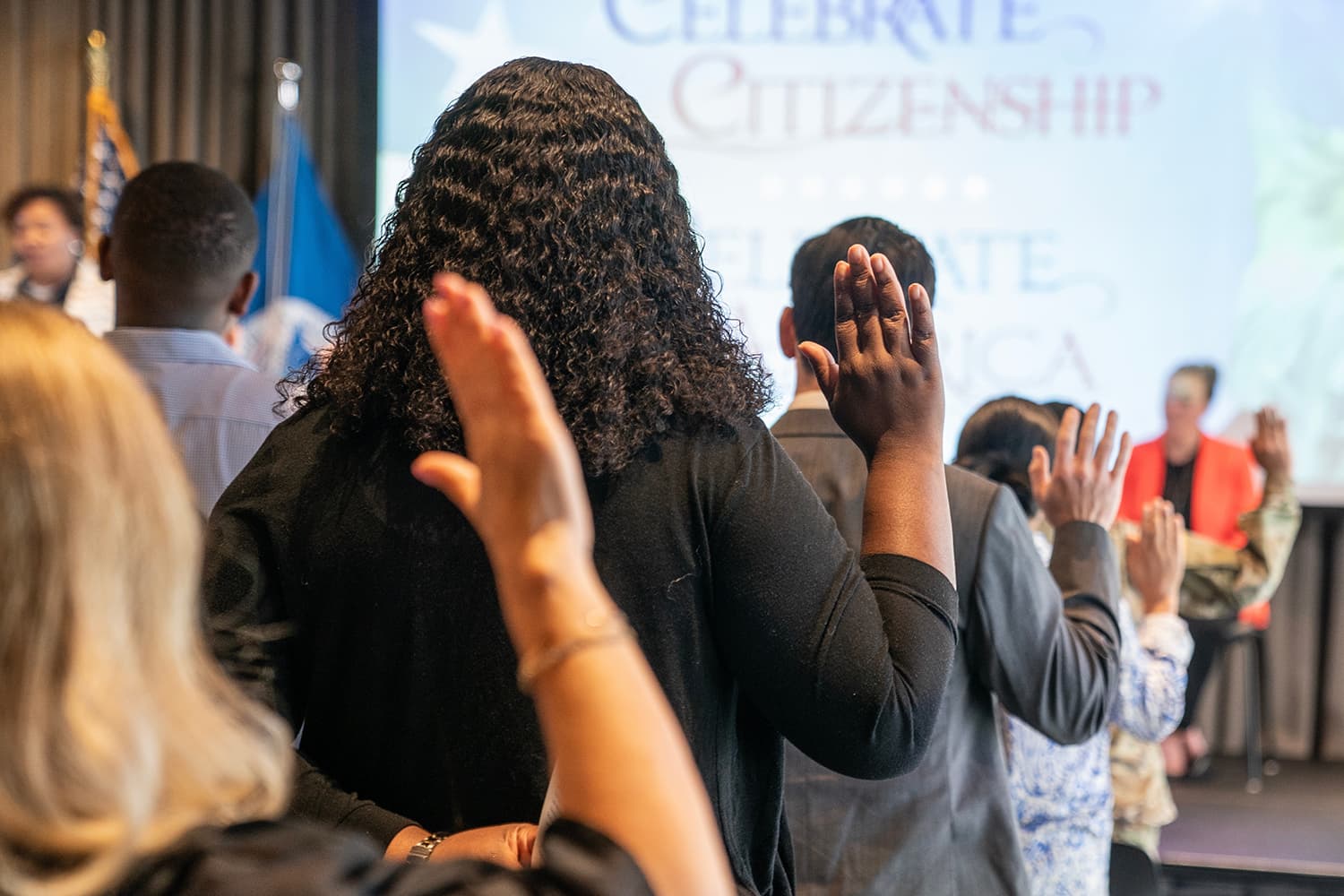

Cover photo: New naturalized US citizen take oath of allegiance at a special naturalization ceremony at New York Public Library on June 30, 2023. Shutterstock/lev radin.