Winter 2012

Papa's Beginnings

– Michael C. Moynihan

50 years after he ended his life, Hemingway lives in the American consciousness mostly in caricature.

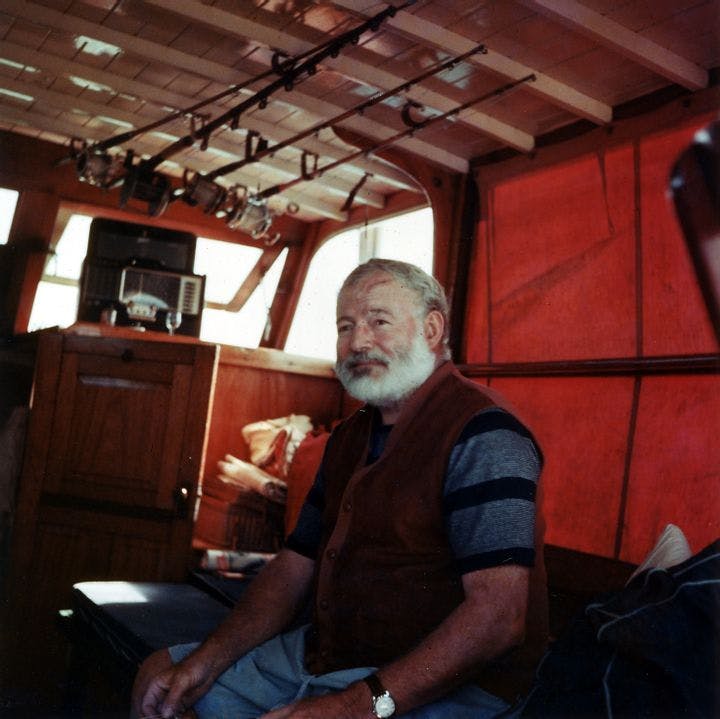

Fifty years after he ended his life, Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) resides in the American consciousness mostly in caricature. The brilliant war journalist and writer of spare, evocative fiction has been overtaken by the macho, absinthe-swilling bohemian, the writer’s life having become more important than the writer’s writing.

There is, of course, something to these cartoonish portrayals. In The Letters of Ernest Hemingway: Volume 1, 1907–1922, the first of a slated dozen or so volumes of his complete, unexpurgated correspondence, the future Nobelist recounts, often in tedious detail, his love of fishing, his heroics on the Italian front, and his burgeoning friendships with expatriate American writers Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein. Unlike previous collections of Hemingway’s letters, this one leaves nothing on the cutting room floor. (The volume begins with a note from an eight-year-old Hemingway to his father.)

Much of the material in this collection, meticulously edited by Hemingway scholars Sandra Spanier and Robert W. Trogdon, will be of interest only to academics and obsessives. The earliest material is a slog: anodyne correspondence with family members, quotidian letters about school life, an exhaustively detailed expense report to his employers at The Toronto Star.

But the multiple accounts of his wounding in World War I—boastful, repetitive, and sometimes stingy with the truth—are fascinating, offering a glimpse of Hemingway’s late teenage worldview. The young men he encountered in Italy, the cannon fodder for Kaisers and kings, would ultimately provide the contours of his most famous literary creations (Nick Adams, Jake Barnes), though the famously economical prose style isn't on display here; his letters are slang filled and overwritten, providing few hints of the crisp style that characterizes his first story collection, In Our Time (1925).

It’s commonly believed that Hemingway was emotionally scarred by his experience in the Great War. Indeed, Thomas Putnam, director of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, which houses many of these letters, argued in an essay a few years ago that “in reaction to their experience of world war, Hemingway and other modernists lost faith in the central institutions of Western civilization.” In A Farewell to Arms (1929), Frederic Henry, a character largely drawn from Hemingway’s experiences in Italy, famously declares, “Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene.”

But if Hemingway believed that Western civilization was in crisis, these letters suggest that his views were arrived at after the armistice. For writers including Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, and Wilfred Owen, the battlefield was where their antiwar beliefs were forged. Hemingway’s opinions were likely influenced by the intellectual ferment of Paris, where he and his wife lived for several years in the 1920s.

In a 1917 letter to his sister, Hemingway writes that he “cant [sic] stay out much longer,” and that he is considering enlisting in the Canadian military if America remains on the sidelines. When a munitions plant explodes at the front, Hemingway writes to a friend that it was his “baptism of fire” and that he is “having a wonderful time!!!” He mentions a field “black” with corpses, not to reflect on the hideousness of the fight, but to explain the provenance of his pile of war souvenirs, and he later confesses that “what makes me hate this war” is that there is no place to fish. The Hemingway of 1918 is more Ernst Jünger than Erich Maria Remarque.

It is only when Hemingway and his new bride, Hadley Richardson, relocate to Paris in 1921 that the reader notices the emergence of a distinct voice, full of the stylistic flourishes and vivid descriptions that would become his trademark. In letters to Pound, Stein, and novelist Sherwood Anderson, whose attention and validation he craved, Hemingway writes to impress, taking significantly more care than in any previous correspondence. The juvenilia are replaced with comments on T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and anecdotes about teaching Pound to box.

This volume ends just as Hemingway is getting started. It’s a collection whose existence goes against his wishes; he had instructed that “none of the letters written by me during my lifetime shall be published.” We can be grateful that his wish was betrayed.

* * *

Reviewed: "The Letters of Ernest Hemingway: Volume 1, 1907-1922" Edited by Sandra Spanier and Robert W. Trogdon, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons