Winter 2012

The True Believers of Jonestown

– Darcy Courteau

Today, we mock blind followers by saying they have “drunk the Kool-Aid.” Perhaps we should correct that unsympathetic characterization of the Jonestown faithful.

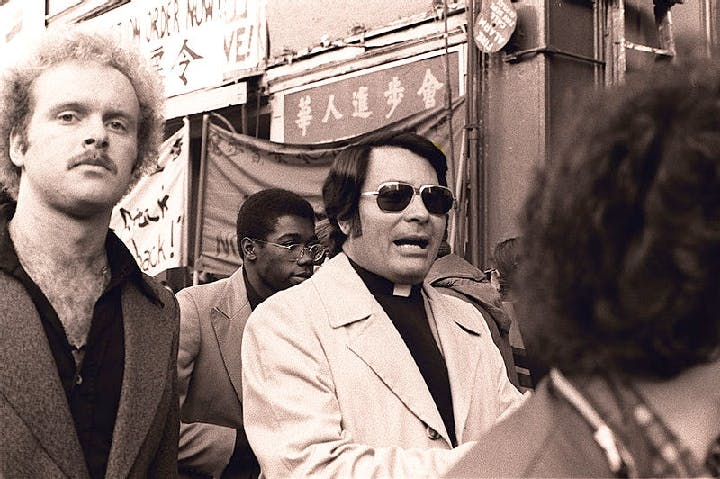

On November 18, 1978, more than 900 Americans living in a socialist collective in Guyana were murdered or took their own lives. Many poisoned themselves with Flavor Aid laced with cyanide. Their bodies were found scattered around Jonestown, the plantation they’d carved out of the jungle four years earlier at the behest of their leader, Jim Jones. He had promised his followers an egalitarian utopia, but Jonestown defectors had returned to the United States calling the place a prison. Leo Ryan, a Democratic congressman from California, led a small entourage to Guyana to investigate. When Jonestown gunmen killed Ryan and several others, Jones ordered aides to roll out stockpiles of poison; he and his followers would find peace in death before the authorities arrived.

Americans have been darkly fascinated with the event ever since—it’s the subject of numerous books and documentary films. Today, we mock blind followers of any stripe by saying they have “drunk the Kool-Aid.” In A Thousand Lives, journalist Julia Scheeres attempts to correct that unsympathetic characterization of the Jonestown faithful. She knows evangelism’s destructive side intimately—in her 2005 memoir, Jesus Land, she described how her zealot parents packed her and an adopted brother off to a brutal Christian reeducation camp in the Dominican Republic.

Scheeres brings her special understanding to bear on the lives of five Jonestown residents, most of whom survived the mass suicide: a man trying to keep his troubled family together, his rebellious son, an elderly black woman searching for a desegregated house of worship, an idealistic schoolteacher, and a kid from the Oakland ghetto determined to stay out of jail. Scheeres is a gifted storyteller, and her characters’ reconstructed conversations and thoughts are a testament to extensive interviews and research that relied, in part, on the hundreds of audiotapes and 50,000 pages of diaries and personal notes the FBI recovered from the site.

When Jones founded his Peoples Temple in the mid-1950s in Indianapolis, desegregation was a cornerstone of the church—a majority of his followers were black. (Jones himself was a white man born in rural Indiana.) A decade later he moved the congregation to California, where he performed phony healings even as he trashed the Bible and claimed personal divinity.

The Temple’s live-and-let-live ethos soured. Jones slept with congregants, demanded their paychecks, and meted out spankings with a belt. Eventually, a journalistic exposé spurred his retreat to Jonestown, whose remote jungle location allowed for even greater abuses. People worked soil too poor to feed them while Jones feasted on barbiturates, chicken dinners, and Diet Pepsi. Naughty children were fed hot peppers or dangled upside down in a well. And Jones staged a series of “White Nights,” during which he pretended that Jonestown was under attack, and conducted suicide drills with fake poison.

Jones’s actions were horrific, but some of the book’s most anguished accounts are of the cruelty his followers heaped on each other, ratting out family members or offering to kill a captured runaway. Ultimately, however, Scheeres concludes that the people of Jonestown were “noble idealists” and innocent victims betrayed by a single man.

The reality seems more complicated than that. It is true that not everyone who died at Jonestown freely chose to cash it in. An iconic photograph of Jonestown corpses shows a pair of tiny legs lying in a stack of jeans-clad rumps. Among the dead were 304 children; dozens of adults were forcibly injected with poison. Certainly, many of the faithful ended up being exploited instead of finding the equality they sought: Blacks slaved in the plantation’s fields, and women became Jones’s concubines. But it is also true that camp guards carrying weapons they could have used for self-defense forced their comrades to die and finally killed themselves. The man who terrified and seduced wasn't all-powerful.

Indeed, Jones was so messed up on downers by the time he summoned the cyanide that he slurred his words as he recorded what now circulates on the Internet as the “Death Tape”: Residents, each carrying a private mix of reasons they’d sought to live in Jonestown—fears, loyalties, ideals, the need to be close to a father or to absorb just a bit of Jones’s power—have crowded around. For several minutes, Christine Miller, a black woman, argues with Jones. There are alternatives, and it isn't right to kill the children. “We all have a right to our own destiny as individuals,” she tells Jones, who listens patiently, paternally—before allowing the others to shout her down.

* * *

Darcy Corteau, a former assistant editor of The Wilson Quarterly, has written for publications including The Atlantic.com, The American Scholar, and The Oxford American.

Reviewed: "A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jamestown" by Julia Scheeres, Free Press, 2011.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons