Spring 2016

Pariah: Can Hannah Arendt Help Us Rethink Our Global Refugee Crisis?

– Jeremy Adelman

Camps and pariahs are still with us. They have never been more numerous.

Hannah Arendt was on her way to lunch with her mother Martha when a Berlin policeman arrested her and took her to the presidium at Alexanderplatz. It was 1933. Hitler had been in power for several months; Hermann Göring’s agents were rounding up suspicious activists. The young researcher for the German Zionist Organization spent eight days in jail while gendarmes scoured her apartment, examined her philosophical notes, and pored over her mysterious codes — a selection of Greek quotes. Upon her release, she packed her bags. Since the torching of the Reichstag in February, life had become hell for socialists, communists, and Jews. Like others before her, and more after, Arendt fled to Paris. She would spend the next 18 years as a refugee, a stateless person, a pariah.

There are 60 million refugees in the world, the highest sum of pariahs since 1945. The figure tripled in the past year alone. Half of the world’s unwanted are under age 18. Most will grow up in a camp. Many will die escaping their places of origin; more than 3,000 refugees drowned in the Mediterranean in 2015. The lucky ones will make new homes. But how welcome they will feel can be gauged by the decibel level of nativists like Donald Trump, a chorus of Republican governors and candidates, Marine Le Pen in France, and the surging Danish People’s Party. So long as these negative voices have the megaphone, can the resettled ever feel at home?

This human condition needs to be taken more seriously. It is fast becoming the worst humanitarian crisis of our times. Nativists are making it worse by denying a tradition of granting asylum to the stateless. We have seen the cycle before — and it never looks good. People look back on shut-them-out policies with shame (this is certainly the way Americans, Canadians, and others view the treatment of asylum-seeking Jews in the 1930s and 1940s). Are we destined to repeat the cycle? If we cannot come up with a coherent response to the nativists in our midst, the answer will be yes, and the consequences for relations with and within the Islamic world and other emergency zones will be lasting. Can Hannah Arendt, the avatar of public philosophy, help us formulate an enlightened response? Can this former refugee help us reaffirm our obligations to people who have nowhere else to turn?

The answer is steeped in her years as a pariah and her insights into dehumanization. Arendt’s own stateless experience helped forge the elements of the book that would make her famous in America and worldwide. The Origins of Totalitarianism was finished in the summer of 1950. In it, she noted that “a man who is nothing but a man has lost the very qualities which make it possible for other people to treat him as a fellow man.” Without a political community, man was a pariah. Months later, Arendt closed a long, agonizing chapter of her life and became a naturalized citizen of the United States, a pariah no more.

And yet, her statelessness is often forgotten. We recall her German years and the romance with Martin Heidegger, the source of much fretting about the limits of her idealism. And we remember her American years. When I first read The Origins of Totalitarianism as a student, it was a Cold War classic. There were many beery nights in the 1980s arguing about the difference between authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, disputing the ideological distinctions of President Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy. We obsessed about what kind of state ruled. But what it means to have no state at all? Not really.

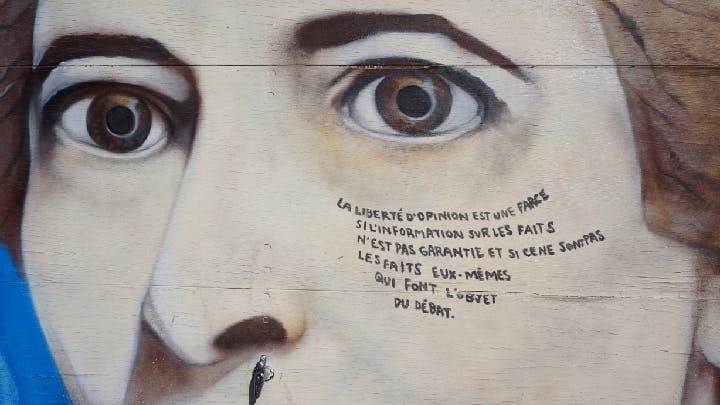

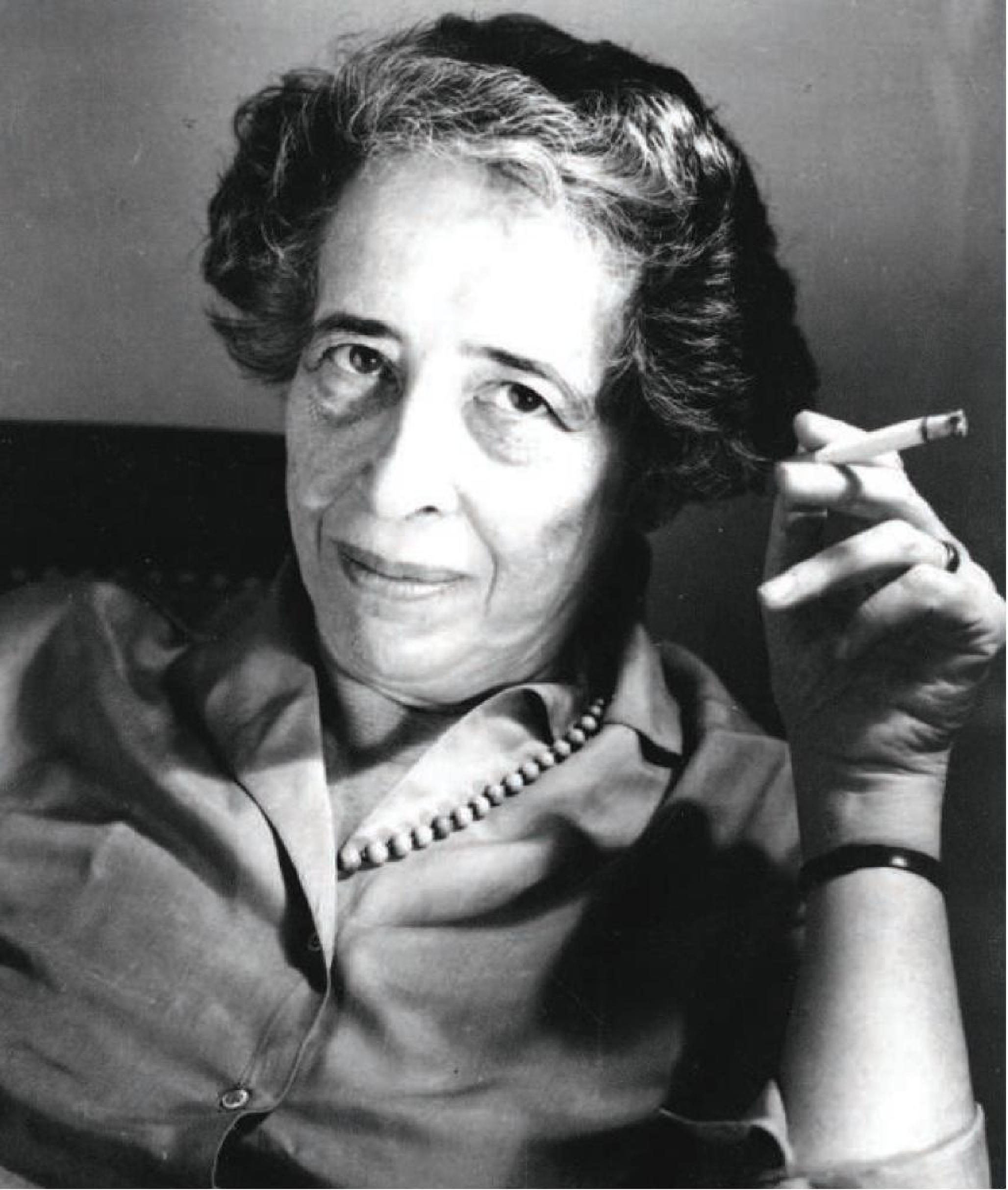

Nowadays, in our age of terror and fugitives, there is another way to read The Origins. There is a different Arendt to remember — not the American made famous by Cold War politics or her searing words about the Eichmann trial and the banality of evil, but the stateless Arendt posing for such an iconic image that we have forgotten the reasons for her mournfulness.

* * *

The Origins of Totalitarianism is a book drawn from a well of personal experience. Arriving in Paris, Arendt moved around the small hotels of rue Saint Jacques in the student quarters of the Left Bank. She was married to a fellow philosopher, Günther Stern, but by then it was a union in disarray. They officially divorced in 1937, and Stern left for the United States. She would eventually meet Heinrich Blücher. Not a Jew, but a self-taught communist, Blücher was a pariah in his own way. The two moved to an apartment on rue de la Convention in the 15th arrondissement, a quartier swelling with expatriate Germans. The rent came from bits of her mother’s gold, smuggled out of Germany as buttons sewn to her clothes and hocked to a wealthy female Jewish patron for cash. Refugee conditions were squalid. Living nearby, the exiled economics student Otto Albert Hirschmann (known to us as Albert O. Hirschman) had to combat a cockroach plague so that he and his sister Ursula (the target of Blücher’s seductions before he met Arendt) could sleep. The solution: place the bedposts in pots of kerosene so the swarm of insects could not climb up the furniture and into the bed.

Exile means eviction from one’s political community. But it also brings fresh encounters. To be unwanted is never just about being rejected by those who throw you out. It also entangles refugees with the ambiguities of their hosts. In the case of the legions of Central European Jews fleeing to Paris and London, exile meant dealing with the establishment Jews who often ran the charitable organizations that took care of the fugitives. Arendt made sense of her pariah-hood in brushes with a different Jewish condition: these upstart, establishment Jews. She called them “parvenus,” and they loomed large in her thinking about the Jewish condition and statelessness.

To be unwanted is never just about being rejected by those who throw you out.

Unable to assimilate fully, parvenus were committed to doing everything possible to make believe that they were. Arendt’s first book was about Rahel Varnhagen, the Enlightened society woman whose salon was a famous gathering spot for learned Berliners — that is, until rising Prussian nationalism during the Napoleonic Wars cast a pall over the Jewess. Even her fiancé dropped her before the wedding in his rush to affirm Teutonic loyalty to the Christian nation. Finished as Hitler assumed power but not published until 1958, Rahel Varnhagen had a personal dimension for Arendt. In January 1933, as she put the final touches on the book, she wrote her mentor, Karl Jaspers, that she was a German by culture, language, and philosophy, but not in character: “I know only too well how late and how fragmentary the Jews’ participation in that [German] destiny has been, how much by chance they entered into what was then a foreign country.” For all that the parvenu desperately tried to avoid the pariah, they were tied at the hip. In the bourgeois age, every generation of Jews had to decide which road to take: to conform and hide one’s origins, or to watch the world from the margins. Both, Arendt noted, “were equally ways of extreme solitude.”

The move to Paris brought parvenus up close. Arendt’s previous work for the German Zionist Organization (and some contacts) eventually led to a meeting with Baroness Germaine de Rothschild. One could not imagine a more suitable emblem of the type. The baroness was the matron of the upper-class Consistoire de Paris, which oversaw schools, synagogues, religious courts, kosher shops, and a seminary. Arendt’s job was to oversee the grandee’s donations to Jewish charities, which left her with a mix of admiration for the private work among the have-nots and impatience at the baronial aversion to principled public stands.

As Arendt crisscrossed the line between the world of pariahs and their cockroaches and the world of the parvenus and their soirées, nativists rampaged in the streets. The Paris grisaille broke with a scandal that nearly brought down the Third Republic. Alexandre Stavisky, a Russian Jew who had worked his way up from soup factory worker to financier, had made a fortune off glossy bonds backed by the emeralds of “the Empress of Germany.” The jewels turned out to be glass, and the whole scheme came down in a great public scandal. By then, Stavisky’s influence in the press and the corridors of power were notorious, spreading accusations of that perennial bestseller, the Jewish conspiracy. After his mysterious death in January 1934 — officially ruled a suicide but considered by many to have been murder — a number of ministers in the French government, including Prime Minister Camille Chautemps, had to resign.

When the new government tried to purge the police of its notorious reactionary, anti-government commanders, the French Right unleashed its fury. On February 6, 1934, the Place de la Concorde became a battlefield for nationalists and police. The brawling left 15 rioters dead. Aghast, Arendt filled her notebooks with newspaper clippings on the scandal and the resurgent French anti-Semitism. She also grew dismayed about the parvenus. As far as they were concerned, keeping a low head was the best way to keep it on one’s neck.

Fascination and dismay sent Arendt back to l’Affaire Dreyfus of the 1890s, the first public scandal about Jewish threats to French values. The trumped-up treason charges against the Alsatian Jewish officer, Alfred Dreyfus, led to a furious debate and rocked the Third Republic. The episode would loom large in Origins as an example of parvenu folly and of the false promises of liberté in a country committed to patrie. The parvenus had remained quiet, and left the outcry against anti-Semitism to be led by non-Jews of principle, like Émile Zola, whose open letter J’accuse immortalized the image of the intellectual bearing witness to the abuse of power. Parvenu silence, by contrast, made them complicit with the abusers. This was, Arendt insisted, not a cause, but a condition of terror, and presaged a more dramatic choice 40 years later. “The main actors,” she wrote in Origins, “seem to be staging a huge dress rehearsal for a performance that had to be put off for more than three decades.”

Arendt’s perspective on the Dreyfus Affair anticipated later accusations that she lacked compassion and love for her people. It is a thorny subject in Arendtology, and divides the Arendt-bashers from her admirers. It comes up in the charges of Jewish self-hatred after the 1963 publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem. That book became an icon for victim-blaming: If she accused Jewish leaders of doing too little to defend their communities against the onslaught, her critics, starting with Norman Podhoretz in Commentary magazine, accused her of doing too much to blame Jews for their ruin (he preferred the good-versus-evil narrative and the sacralizing of the Holocaust in Jewish memory as the modern defining trauma). For her apostasy, Arendt was being banished once more as the treasonous Jewess. The myth of Arendt’s self-hatred goes on. The 2013 film Hannah Arendt by Margarethe von Trotta makes allegations of Jewish self-hatred the centerpiece of the drama, though in doing so the film depicts Arendt as a universal symbol brought low by lip-snarling Zionists. The mythologizing either way misses the message about the specific condition of the pariah. Arendt never accused all Jews of self-inflicted genocide; it was the silent, complicit leaders she charged with not doing more to defend those who could not speak.

Arendt never accused all Jews of self-inflicted genocide; it was the silent, complicit leaders she charged with not doing more to defend those who could not speak.

Trials loom large in this saga. Dreyfus. Eichmann. Consider how Arendt responded to Kristallnacht, the night of November 9, 1938, when Nazi gangs tore through Jewish shops and homes: Arendt was as horrified as others at the Nazi zeal to destroy. But she was also dismayed that French Jewish leaders distanced themselves from Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew whose murder of a Nazi diplomat in Paris in November 1938 became the pretext for thugs to go rampaging in Germany. As she tore through the newspapers, taking notes and collecting clippings, Arendt treated Grynszpan’s trial as a test of Jewish leaders’ commitment to their own. Instead of making sure the pariah got a fair trial, however, they sacrificed Grynszpan with silence.

Even here, the line that divides the pariah without rights to use from the parvenus with rights they refused to use is not so hard and fast. Capable of being merciless, Arendt did appreciate the pathos of the parvenus: they claimed a home they could never sure of. This was the significance of Rahel Varnhagen’s solitude. In exile, Arendt came to see what the parvenu always knew: home could not be taken for granted. This precariousness motivated the quietude. While Eichmann in Jerusalem had scabrous things to say about parvenus’ roles in the destruction of the Jews, what fired up Arendt was her sense that those who had rights had a duty to wield them for those who had none. If they were guilty, it was not that parvenus had given up their rights; it was that they did not defend those who did not have any rights.

In exile, Arendt came to see what the parvenu always knew: home could not be taken for granted.

* * *

A silhouette of Hannah Arendt’s book took shape against Europe’s darkening skies of 1938. At the urging of her friend Walter Benjamin, whose apartment on rue Dombasle in the 15th arrondissement became a second home, and where she and Blücher spent long evenings discussing events, Arendt started to compose her ideas. Meanwhile, German repression and the annexation of Austria sent new waves of pariahs to Paris.

While she was not volunteering to help refugees, Arendt was frantically taking notes, aware that a reckoning was coming. When France declared war in September 1939, there was a long pause known as the drôle de guerre, or “strange war.” The French government began to round up suspicious Germans. Men like Blücher had to report to work camps. Released after a few months, Blücher returned to Paris; he and Arendt arranged a hasty marriage on January 16. Getting a French marriage certificate may have saved both their lives: several months later, Hannah and Heinrich went from being pariahs together to becoming prisoners apart, and their marital papers would eventually be a ticket out.

As Panzer divisions hurtled across the borders, the French government summoned all German, Saar, and Danzig-born men between ages 17 and 55, as well as women without children, to report to the prestataire of internment camps. The men went to the Stade Buffalo, women to the notorious Vélodrome d’Hiver, now known as the Place des Martyrs Juifs, at the edges of the 15th arrondissement. (Two years later, it was from this arena that the Jews of Paris would be herded onto trains and sent to Auschwitz.) After a week on cement bleachers, Arendt and others boarded buses. Passengers sobbed as the caravan left Paris for Gurs, a camp for Spanish refugees and International Brigade fighters. Cut off from the world, the internees did their best to stave off boredom and anxiety with routines and rituals. When France fell to the Nazis six weeks later, apprehension turned to panic; rumor spread among Gurs inmates that they would be turned over to the Gestapo. Some were able to use naturalization certificates and marital papers as passports to get out. Arendt walked out of the gates into the chaos of the first days of Vichy France.

The Origins of Totalitarianism took form in the ensuing dangerous, heartbreaking months. Vichy France was the picture of turmoil. Millions streamed from the Nazi-occupied north. The roads were clogged with bicycles, carts and cars. Arendt walked and hitchhiked to a friend’s house in Montauban, a provincial town not far from Toulouse, and sent word of her location to Paris. One day, while walking on Montauban’s main street, she ran into Blücher, who’d been released from his camp when German troops entered Paris. The two embraced in the bedlam of mattresses, furniture, and discarded toys of refugee children. They found a vacated house and parked themselves, waiting.

While the summer of 1940 rolled out Marshal Philippe Pétain’s anti-Semitic decrees, Arendt sat in the garden or at her makeshift desk, reading and taking notes. It was in Montauban that she read the works of the half-Jewish Marcel Proust, who would figure prominently in The Origins — the writer who transformed “worldly happenings into inner experience” just as Arendt was turning her inner experiences into reflections on the world. He was her witness on bourgeois France’s soulless ambitions and disintegration into an ensemble of cliques drained of self-respect or virtue, intolerant of outsiders, Jews, or “inverts.” A dejudaized Jew, Proust observed a world he could only partially belong to, not least because he was also gay. The garden was also the setting where Arendt digested Clausewitz’s On War, which does not figure in Origins but which cued her to the collapse of Europe’s state system. Borrowing from Clausewitz, Lenin had argued that the collapse of the state system in the First World War had created the conditions for revolution; for Arendt, another collapse created the conditions for the opposite a generation later.

As with Lenin, Arendt’s meanderings led her to imperialism. When anti-Semitism inseminated Europe’s conquering habits — she dates its conception to 1884, the year of the Berlin Conference that carved Africa into possessions — the world got what she called “racial imperialism.” It pivoted Europeans to the Dark Continent for gold and diamonds. (Latter-day critics of Wall Street should consider mining chapter five of Origins for some choice vitriol for those who pursued “superfluous wealth” by created “the first paradise of parasites.” The “first class to want profits without fulfilling some real social function” inaugurated their careers by producing the most “unreal” of goods.) The ruin of Africa and the persecution of the Jews were two faces of European nationalism’s descent from benign patriotism to savagery. Racial imperialism spiked just as the system of European nation-states spun out of control, bringing up all the forces lurking below the gentile surface. The money, the legends, empire, sops for the mob, and the promise of unlimited imperial expansion “seemed to offer a permanent remedy for a permanent evil,” wrote Arendt. High society and low could now lock arms and, as Arendt whipped herself into an apocalyptic conclusion, destroy the earth:

“For no matter what learned scientists may say, race is, politically speaking, not the beginning of humanity but its end, not the origin of peoples but their decay, not the natural birth of man but his unnatural death.”

* * *

Staying in France meant camps and deportation to Germany, or hiding; there was no refuge. By summer’s end, an American named Varian Fry had teamed up with Hirschmann, now operating as Albert Hermant “née a Philadelphie” — Fry would joke that his right-hand man had too many identities to be trustworthy — to create the Emergency Rescue Committee operation in the Hotel Splendide in Marseilles. Together, they worked the port’s demimonde of mobsters, fraudsters, and prostitutes to turn American visas into getaways, with bogus transit passes, departure permits, money, and an escape trail over the Pyrenees. Young Aliyah, a Zionist group, got Arendt and Blücher American visas. Now, the pair needed a way out of France. They bicycled to Marseilles to find it.

It was in Marseilles that they caught up with Walter Benjamin, who also had a visa and planned to work at the Institute for Social Research in New York. Escape, however, was fraught with risks. Like many refugees, Benjamin was a wreck. Arendt did her best to bolster his hopes; in return, in case something happened, Benjamin gave her his manuscript, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Then he made for the Pyrenean crossing at Portbou on September 25. After a long mountainous trek, he reached the Spanish customs house, but General Francisco Franco’s man turned Benjamin back; that day, transit visas would no longer be honored. Stuck between a France that did not want him and a Spain that refused to let him pass, alone, in the dark, a distraught Benjamin committed suicide with an overdose of morphine pills. Months later, when Arendt and Blücher had escaped with the help of the Emergency Rescue Committee and were sailing to New York from Lisbon, they opened Benjamin’s packet. The pariahs took turns reading “Theses” to each other aloud as a small crowd gathered to listen to the philosopher’s last words.

_(14597566077)_Wikimedia.jpg)

While in Montauban, Arendt had drafted a long memorandum to Erich Cohn-Bendit. It became the heart of chapter nine of Origins. Arendt and Cohn-Bendit had spent evenings together at Benjamin’s apartment on rue Dombasle. The memo concerned the Minority Treaties negotiated by the architects of world peace in Paris in 1919. It was a devastating indictment of the men of Versailles. In the nation par excellence, peacemakers conjured the minority par excellence, and all but sealed its fate. The Minority Treaties were a compromise. When Woodrow Wilson came to Europe brandishing his idea of self-determination for all nations as a ticket to peace, he faced a problem: what to do about Europe’s minority populations, especially those that had been created by the self-determining nations carved out by the peacemakers? The compromise was to have new states sign, one by one, separate treaties that would protect domestic minorities as a condition of membership for new nations in the new League. Conveniently, the victorious Great Powers were exempted from the condition — to the dismay of W. E. B. Du Bois, who yearned to extend minority protections to the United States, and had been lobbying the Great Powers, including his own president. Dejected, Du Bois returned from Europe in 1919 only to face a summer of butchery with few parallels in the bloody history of race in America, and composed his most ominous essay, “The Souls of White Folk.”

Sometimes, compromises work. This one did not. To Arendt, it was destined to fail because the men of Versailles had refused to understand that making peace by lumping people into new states and handing power to majorities consigned the non-members of newborn nations to go from misérable to indésirable. Across eastern and central Europe, they were destined to become the new pariahs in a world that was supposed to be made peaceful with nation-states. It was, Arendt charged, “an open breach of promise and discrimination.” No wonder that the frenzy for nation-building also produced the modern political refugee. All this was utterly predictable. “The danger of this development,” Arendt wrote, “had been inherent in the structure of the nation-state since the beginning.” Instead of recognizing that the nation-state was the ailment, peacemakers spread it around.

No wonder that the frenzy for nation-building also produced the modern political refugee.

The Minority Treaties were charters for Jewish ruin. Jews, after all, were minorities everywhere but wanted nowhere. But what made Jews the minority par excellence was that their plight was singled out —by Jews and non-Jews alike — as a “Jewish problem.” Once the fate of the Jews was theirs alone, the deal was done. Unlike Germans, who had a state that muscled to their defense on bogus grounds (like Hitler “rescuing” ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland in 1938), the Jews had no such thing. The perfect pariah could now be made the ideal scapegoat.

Then came the roll call of surprise. Bystanders were shocked when Hitler denationalized the Jews, shocked when the Jews became refugees, shocked when they could not get rid of them, and shocked when these stateless and unwanted minorities got rounded up for the slaughter. Had these bystanders been more aware of the perils of deriving rights from national sovereignty, Arendt concluded angrily, they should not have been nearly so shocked. The modern story of the Jews became a chapter in world history because “the arrival of the stateless people brought an end to this illusion” that nationality served human rights.

The modern story of the Jews became a chapter in world history because “the arrival of the stateless people brought an end to this illusion” that nationality served human rights.

* * *

After settling into a Manhattan apartment on the corner of West 95th Street in 1941, Arendt and Blücher argued, smoked, and plowed their way through a proposal to book publisher Houghton Mifflin. Arendt called it The Three Pillars of Shame. “The aim of the book,” she later told her editor, Mary Underwood, “is not to give answers but rather to prepare the ground.”

Ground for what? While working for the Conference on Jewish Relations, she wrote poems and took long walks with her husband along Riverside Park to figure that out. All the while, news of the horrors came in, including a report that the detainees of Gurs had been shipped to Auschwitz. In a forgotten short essay written in January 1943, Arendt reckoned that Jews had to accept what they had become. Unable to console themselves as “newcomers” or “immigrants,” they were now “refugees.” They joined a new category of people on earth, a category no one wanted to talk about. “Apparently nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings,” she wrote, “the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends.” The pariah who had survived focused her grief and rage into a work of singular insight into what had made evil so radical:

The real horror of the concentration and extermination camps lies in the fact that the inmates, even if they happen to keep alive, are more effectively cut off from the world of the living than if they had died, because terror enforces oblivion.

Something had entered politics, “some radical evil,” that was not previously known and should never have been admitted. The idea that entire races could be gassed out of existence was no longer just a possibility.

As she put the final touches to the book, Arendt was aware that the end of the war did not put an end to consigning entire peoples to pariahdom. By 1949, the camps were filling up again. Not just the gulags, but on the borders of India and Pakistan, and — most tragically for Arendt — around the rim of the new state of Israel. At one point, she stepped from the pages to speak to her reader in their shared present:

No paradox of contemporary politics is filled with a more poignant irony than the discrepancy between the efforts of well-meaning idealists who stubbornly insist on regarding as “inalienable” those human rights, which are enjoyed by citizens of the most prosperous and civilized countries, and the situation of the rightless themselves.… The internment camp has … become the routine solution for the problem of domicile of the “stateless persons.”

Was this the “ground?”

How did the camp become a “routine solution” after a war that had made us so aware of its horrible truths? The trouble was not just with the criminals, though we had zeroed all our attention on the criminals of Nuremberg. It also lay at the door of those who wanted to play the role of angels who sang the lyrics of human rights as though they were natural, while forgetting — in the most famous of Origins’s lines — “the existence of a right to have rights.”

It is only thanks to our institutions that we become equal.

Arendt was famous for the scorn she heaped on happy pieties that realities hollowed out. Among her choice targets of platitudes: we are all born equal, destined for liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We are not. It is only thanks to our institutions that we become equal. Our organizations enable us to live in freedom. Humans, she noted, enjoyed rights only as long as they were members of political communities; the minute they left, or were banished, their rights were gone, and only their frail and perishable humanity remained. It would take a stateless woman to remind the public that these rights are not natural. It took an alien to say it: these rights can be taken away. Worse even: people can find themselves in a world where no one wants them any more, and these rights cannot be regained.

It would take a stateless woman to remind the public that these rights are not natural. It took an alien to say it: these rights can be taken away.

The real plight of the pariah is not just to be driven from home. That has been a misfortune of our world for a long time. God did it to Adam. Rulers have made outlaws from time immemorial. No, what singled out the modern age was that no one would take in the pariah.

This is where the angels had a role. For in the festivities of national self-determination and the affection for Rights of Man as a creed outside history — where rights existed as self-evident and inalienable — those with the power to celebrate good things had forgotten the scum of the earth. The totalitarians had guile enough to say what most pariahs knew but could not: “no such thing as inalienable human rights existed and that the affirmations of the democracies to the contrary were mere prejudice, hypocrisy, and cowardice in the face of the cruel majesty of the new world.”

So long as the democracies clung to their pieties, they could never truly see that there had to be “rights to have rights” — which included reserving a place for the persecuted. Once the tyrants saw this, there were few limits to their solutions for the unwanted. Seeing that no one wanted the Jews, Hitler could turn on the gas and solve everyone’s problem. As Arendt wrote, “A condition of complete rightlessness was created before the right to live was challenged.”

* * *

“I am still a stateless person,” Hannah Arendt wrote to Jaspers months after the war ended, “I haven’t become respectable in any way.” The Origins of Totalitarianism is a book about despots and dehumanizers. But it is also a book about the unrespectable and the unwanted, as well as the rest of us — the shocked onlookers at the horrible things that horrible governments do to people. Arendt’s voice is one we can turn to as we grapple with the spread of statelessness in our day.

Camps and pariahs are still with us. They have never been more numerous. They are products of our world of interconnected nation states. We have a role in creating rights to have rights. It includes our ability to offer sanctuary for those that have none. That, Arendt would argue, is a starting point for saying no to the nativists at home and taking a stand against the tyrants abroad.

* * *

Jeremy Adelman is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History and director of the Global History Lab at Princeton University. The author or editor of ten books, his next project is a book on global thinking called The Opening of the Global Mind. Cover photo courtesy of Steve Browne and John Verklier