Refugees and the Technology of Exile

– David Lepeska

Apps, real-time translation services, and other online tools are helping Syrians and other refugees in Turkey forge new lives for themselves.

When the uprising against Syrian president Bashar al-Assad began five years ago, Mojahed Akil was a computer science student in Aleppo. Taking to the streets one day to protest with friends, he was arrested, flown to Damascus, beaten, and tortured. “They punched me over and over. They strapped my wrists to the ceiling and stretched my body as far as it could go,” the 26-year-old said calmly during a recent interview in the offices of his small tech firm in Gaziantep, Turkey, some 25 miles from the Syrian border. “This is very normal.”

Akil’s father, a businessman, paid the regime to release his son, who fled to Turkey. There, he ran into a massive language barrier. “I don’t know Turkish, and Turks don’t speak English or Arabic,” he recalled. “I had difficulty talking to Turkish people, understanding what to do, the legal requirements for Syrians.”

While working for a Turkish tech firm, Akil learned how to program for mobile phones, and decided to make a smartphone app to help Syrians get all the information they need to build new lives in Turkey. In early 2014, he and a friend launched Gherbtna, named for an Arabic word referring to the loneliness of foreign exile.

As part of its recently finalized deal with the European Union (EU), Turkey has begun to stanch the flow of migrants across the Aegean Sea. But the reason so many of the more than three million Syrians, Iraqis, Afghans, and other refugees in Turkey had seen fit to crowd onto those dangerous rubber boats to cross into Europe is that, for the majority, their lives in Turkey had been rather desperate: hard, infrequent, and low-paid work; limited access to education; crowded housing; a language divide; and uncertain legal status.

About one-tenth of the 2.7 million Syrians in Turkey live in refugee camps. The rest fend for themselves, mostly in big cities. Now that they look set to stay in Turkey for some time, their need to settle and build stable, secure lives is much more acute. This may explain why downloads of Gherbtna more than doubled in the past six months. “We started this project to help people, and when we have reached all Syrian refugees, to help them find jobs, housing, whatever they need to build a new life in Turkey, then we have achieved our goal,” said Akil. “Our ultimate dream for Gherbtna is to reach all refugees around the world, and help them.”

Humanity is currently facing its greatest refugee crisis since World War II, with more than 60 million people forced from their homes. Much has been written about their use of technology — how Google Maps, WhatsApp, Facebook, and other tools have proven invaluable to the displaced and desperate. But helping refugees find their way, connect with family, or read the latest updates about route closings is one thing. Enabling them to grasp minute legal details, find worthwhile jobs and housing, enroll their children in school, and register for visas and benefits when they don’t understand the local tongue is another.

Due to its interpretation of the 1951 Geneva Convention on refugees, Ankara does not categorize Syrians in Turkey as refugees, nor does it accord them the pursuant rights and advantages. Instead, it has given them the unusual legal status of temporary guests, which means that they cannot apply for asylum and that Turkey can send them back to their countries of origin whenever it likes. What’s more, the laws and processes that apply to Syrians have been less than transparent and have changed several times. Despite all this — or perhaps because of it — government outreach has been minimal. Turkey has spent some $10 billion on refugees, and it distributes Arabic-language brochures at refugee camps and in areas with many Syrian residents. Yet it has created no Arabic-language website, app, or other online tool to communicate the relevant laws, permits, and legal changes to Syrians and other refugees.

Turkey has spent some $10 billion on refugees, and it distributes Arabic-language brochures at refugee camps and in areas with many Syrian residents. Yet it has created no Arabic-language website, app, or other online tool to communicate the relevant laws, permits, and legal changes to Syrians and other refugees.

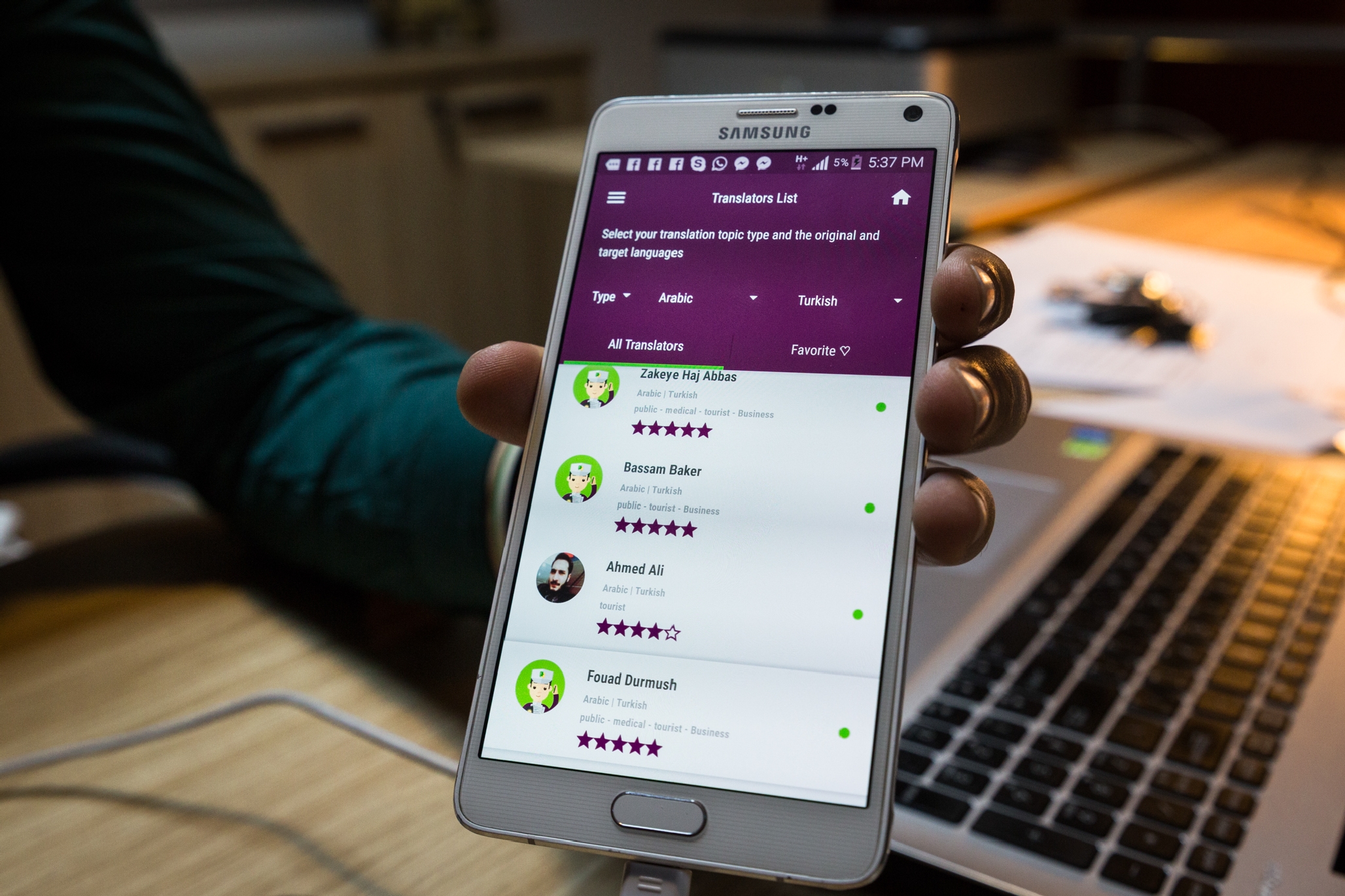

Independent apps targeting these hurdles have begun to proliferate. Gherbtna’s main competitor in Turkey is the recently launched Alfanus (“Lantern” in Arabic), which its Syrian creators call an “Arab’s Guide to Turkey.” Last year, Souktel, a Palestinian mobile solutions firm, partnered with the international arm of the American Bar Association to launch a text-message service that provides legal information to Arabic speakers in Turkey. Norway is running a competition to develop a game-based learning app to educate Syrian refugee children. German programmers created Germany Says Welcome and the similar Welcome App Dresden. And Akil’s tech firm, Namaa Solutions, recently launched Tarjemly Live, a live translation app for English, Arabic, and Turkish.

But the extent to which these technologies have succeeded — have actually helped Syrians adjust and build new lives in Turkey, in particular — is in doubt. Take Gherbtna. The app has nine tools, including Video, Laws, Alerts, Find a Job, and “Ask me.” It offers restaurant and job listings; advice on getting a residence permit, opening a bank account, or launching a business; and much more. Like Souktel, Gherbtna has partnered with the American Bar Association to provide translations of Turkish laws. The app has been downloaded about 50,000 times, or by about 5 percent of Syrians in Turkey. (It is safe to assume, however, that a sizable percentage of refugees do not have smartphones.) Yet among two dozen Gherbtna users recently interviewed in Gaziantep and Istanbul — two Turkish cities with the most dense concentration of Syrians — most found it lacking. Many appreciate Gherbtna’s one-stop-shop appeal, but find little cause to keep using it. Abdulrahman Gaheel, a 35-year-old from Aleppo, runs the Castana Cafe in central Gaziantep, a casual eatery popular with Syrians and aid workers. He used Gherbtna for a couple months. “I didn’t find it very helpful,” he said, sipping tea at a table in the back of his cafe. “It needs to have more content, more news. It should be updated more often, with more sources — this would attract more people.” By contrast, Hassem Trisi, a 27-year-old who is also from Aleppo, has a Gherbtna success story. About six months ago, Trisi, who now runs a mobile phone shop in Gaziantep, felt some pain from a nerve in his neck. “I heard Gherbtna had a list of doctors and specialists,” he said. “I found a good doctor through the app, went to see him, and I’m better now.”

Mohamed Kayali, a 33-year-old web developer from Damascus now living in Istanbul, uses all variety of technology. He found his apartment via the Turkish site sahibinden.com and has found freelance work online. He says that Gherbtna has few exclusive features — much of its content can be found elsewhere. One might say the same about TurkiyeAlyoum, a Syrian-run website that offers daily news as well as regularly updated legal info. Or Alfanus, Gherbtna’s direct competitor, which launched in March. Its Index section is a sort of smartphone yellow pages, with color photos of barbers and beauty shops, Turkish-language schools, Syrian restaurants, and more. It also features a Marketplace, where one can buy furniture, laptops, cars, and iPhones, and a property section, where in March a four-bedroom house with a pool in the Istanbul suburb of Büyükçekmece was going for $450,000.

Kayali says that Alfanus and Gherbtna both need refining. One problem is funding. Mojahed Akil’s tech firm, Namaa Solutions, employs 13 programmers in all. Gherbtna generates income from Google ad sales and advertising from 100 Syrian companies, but it is not enough to cover costs. “These apps are good concepts, but they need to grow up, to mature, like any product,” Kayali said during a recent chat in the sun-dappled back garden of Pages, a Syrian-run bookstore in Istanbul’s Old City. “Developing apps like this requires a lot of time, a lot of money. I don’t think any Syrians here are able to do this yet.”

One tool has had time to mature. Syrians in Turkey use Facebook to find jobs, housing, friends, restaurants, and interesting events. They use it to read the latest news; learn local laws; find a smuggler; or obtain an ID, a residence visa, or a work permit. Syrians have formed Facebook groups for jobs, for housing, for people from Aleppo or Homs — in each major Turkish city. Iyad Nahaz, a 27-year-old techie from Damascus, moved to Gaziantep early this year and found his apartment and his job as a program development officer for the nonprofit Syrian Forum through Facebook. In March, Ghise Mozaik, a 29-year-old entrepreneur from Aleppo, posted a job ad on Facebook, looking to hire a Syrian programmer for his Gaziantep IT firm. “We got all these resumes in one day,” he said during an interview in his office, picking up an inch-thick manila folder. It says a lot that Gherbtna has more followers on its Facebook page (88,000 as of late April) than app downloads.

New translation apps, however, fill a void in Facebook’s suite of services. Souktel’s text-message legal service launched in August 2015, and total traffic (requests for assistance and responses) has already passed 200,000 messages. Some 10,000 Syrian refugees have used the service, and usage is increasing, according to Souktel CEO Jacob Korenblum. Aliye Agaoglu, an Iraqi immigrant, knows all about it. She runs an Istanbul business that provides translation services for Arabic-speaking refugees, helping them get IDs, residence visas, and work permits. “Most of my time is spent answering people’s questions about these laws, because they just don’t understand,” Agaoglu said on a recent afternoon, over tea in her small office in Aksaray, a dense, increasingly Arab district in Istanbul’s Old City. It doesn’t help, she added, that since the summer of 2015, Arabic-speaking migrants are no longer allowed to bring a translator with them when they visit a government office. Syrians’ limited legal understanding is often less about laws than about language. “For Syrians here, it’s unbelievably hard to grasp your situation,” said Rawad AlSaman, a 31-year-old lawyer from Damascus who now works as a salesman at Pages bookstore. “Nobody understands the law because nobody understands the language.”

“Nobody understands the law because nobody understands the language.”

In the language barrier, Mojahed Akil sensed an opportunity, and began developing Tarjemly Live. Launched in February 2016, the app is available only in Turkey and puts a live human translator on the other end of the phone, translating Turkish, Arabic, and English for one Turkish lira ($0.35) per minute, or $0.02 per word for text messages. Tarjemly saw 10,000 downloads in its first month, with 85 percent actually using the app. Ahmad AlJazzar, an 18-year-old from Aleppo living with his family in Gaziantep, discovered the usefulness of Tarjemly when helping a friend who had broken his leg. “I took him to the hospital, where nobody spoke Arabic or English,” he said. “The app worked great, translating our conversation with the doctor right there as we spoke. I’ll definitely use it again.”

The service is available 24 hours a day; Akil has signed up more than 120 translators, most of whom are college students. Tarjemly is far from the world’s first live human translation app, but for many in Turkey it is a godsend, as language remains the biggest hurdle to securing work permits, accessing government benefits, and countless other necessities of building lives here

Akil recently reached a deal with Turkcell, Turkey’s leading mobile operator, which is half state-owned. Now, every Syrian who subscribes to Turkcell receives a text message inviting them to download Gherbtna. Turkcell expects to send out a million of these messages by the end of summer. Akil’s happy about the deal, but wants more. “We want the Turkish government to approve Gherbtna as the official app for information, jobs, and housing for Syrians in Turkey,” he said. “This will help us reach many, many more people.”

Google recently invited Akil to attend its prestigious annual developers' conference, in Mountain View, California. But Turkey rejected his visa application. According to a recent report in Spiegel, in recent months Turkey has refused travel visas and withdrawn permits for many highly skilled Syrians.

The government is doing its part to help Syrians integrate. Recent reports that Turkey has deported thousands of Syrians, and even shot some who were attempting to cross the border, are troubling. But Ankara has issued about 7,500 work permits to Syrians, and in January it passed a law that is expected to make it easier for Syrians to get these permits. It hopes to have 460,000 Syrian children in school by the end of this year, and recently partnered with Istanbul’s Bahçeşehir University to launch a program to teach Turkish to some 300,000 Syrian youth. A senior Turkish government official says that the government is working to put Arabic-language resources online.

But opportunities remain. The $6.8 billion that Turkey is receiving as part of its migrant deal with the EU is expected to go toward housing, education, and labor market access for Syrians. Ankara hopes to direct some of the funds into its health and education budget, for services rendered, but some of those funds might go toward tech tools. Turkey might back Gherbtna, or a translation tool, or even take after Germany, which recently launched a Gherbtna-like app of its own, Ankommen (“Arrive,” in German) to help its one million migrants integrate.

Thus far, technologies that aim to help newly arrived migrants build new lives in Turkey have largely fallen short. They may just need a bit of time, and broader backing from the public and private sectors. Kayali, the Syrian web developer living in Istanbul, says that the ideal app for Syrians and other Arabic speakers would provide comprehensive and regularly updated legal information as well as details on local pharmacies, hospitals, schools, and more.

Ghertbna may be inching closer to that ideal. While we were chatting, Abdulrahman Gaheel, the cafe owner, pulled out his smartphone and opened the app, which he had not used in months. He found 8 to 10 restaurants listed, some interesting jobs, and new ads, including one for a language academy. “This is not like before; there’s more info now,” he said. “It’s getting better — maybe I will start using it again.”

* * *

David Lepeska is an Istanbul-based journalist who has written for the New York Times, the Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, Financial Times, the Economist, the Guardian, and other outlets. His work focuses on Turkey, the Middle East, urban issues, media, and technology.

Photos courtesy of the author