Summer 2013

“Still, God Helps You”

Snatched from a marketplace in Sudan and sold into slavery at the age of six, William Mawwin became one of millions of people in the world enduring some form of involuntary servitude. This is his extraordinary story.

It is Monday morning in Phoenix, Arizona, and 33-year-old William Mawwin is getting dressed for school. His right arm is an old prosthetic the color of Hershey’s syrup. The prosthetic has begun to hurt him, but he cannot afford a new one. On his left hand, four fingers are missing down to the second knuckle. His naked back and chest are welted with raised, pinkish scars, some from beatings, others from burns. More scars, from knife wounds and skin grafts, map his body. In the slow, careful way he has taught himself, he puts on socks, jeans, a neatly ironed shirt, dress shoes with pointed tips. Across from his bedroom, a guest room stands empty except for a twin bed and a chest of drawers. His daughter’s teddy bear sits propped on the pillow. William, who is six feet tall and slender, sometimes just sits on her bed and holds the stuffed bear.

He does not look forward to school holidays, to spring or winter breaks. Each day away from the classroom lengthens his exile, leaves openings for bad memories. He takes the public bus to school or, if he is short of money, walks. His car, an old silver Nissan van, has sat unused since it failed last year’s emission test. He hasn’t got money to fix it. Surviving on a Pell grant and disability payments, William lives sparingly but is still sometimes short on the rent. His apartment complex has changed management, and the new policies include strict penalties for late payments. This morning, he overslept and is late for school, so he needs to borrow his friend’s bright green Discount Cab. He drives to geology class, ignoring calls from the dispatcher, the heel and palm of his fingerless hand guiding the black steering wheel.

On a September evening in 2005, I was hosting a small fundraiser for the Lost Boys Center in Phoenix, too busy to notice the young Sudanese man sitting quietly beneath a tree in my backyard, his stillness like camouflage. Years later, he will tell me how isolated he felt that night. His English was poor, and experience kept him cautious, emotionally distant. He did not trust people’s motives and had told no one his real story. Less than a year later, introduced to William at another Lost Boys event, I extended my hand and was startled by the plastic palm and fingers I touched, brown, shiny, lifeless. Eventually, when this young man began calling me “Mom,” I felt wary of what I might be obligated to do or to give beyond what I was comfortable with, which, frankly, was not much. If the word “mother” is a mythic invocation of selflessness, I owned plenty of selfishness at that point in my life, along with a slew of rich excuses. What I would come to realize, with some shame over this tense instinct for self-preservation, was how much this young man had to offer my two daughters and me. Not materially—for he had and has next to nothing—but by his loyalty and integrity, and by his exceptional story of survival.

When a stranger walks into one’s guarded life, a gift disguised as a potential burden, a gentle rebuke to the narrowest notion of family, then the strengthening of one’s capacity to risk generosity, the incremental increase in one’s courage, feels like uncreeded theology, like some new faith, love’s loftiest ideal made human by a series of small, ordinary acts.

Mawwin attends a kickball tournament with his daughter, Achol, in Arizona in May 2013.

The evening I formally met William and shook his hand, he was with his friend Edward Ashhurst, a filmmaker hoping to make a documentary about William’s life. Ed asked for my professional help, and, intrigued by what I might learn about his process, I agreed. He and William began visiting me, and over a period of several weeks we fell into a routine. William would tell his story, Ed and I would listen, and then all three of us would talk over possible strategies for the documentary. At one point, we even flew to Los Angeles to meet a producer who had shown interest. But before long, the project stalled. I became busy teaching and traveling, and only saw William from time to time. I had also become aware of some slight, unsettling opposition within myself. As much as William’s story of being a child slave haunted me, I was resisting its pull. He had confided terrible things to Ed and me, things he said he had never told anyone; perhaps, I reasoned, the connection I resisted was simply one of bearing witness. Even less comfortable to admit was my fascination with the details and depth of his suffering, again offset by an obdurate reluctance to get too close. Closeness, after all, implies a responsibility that voyeurism doesn’t. So for a very long time my relationship with William stalled too, in uneasy territory. For a long time, I held him at arm’s length.

Today, more human beings suffer enslavement than during the three and a half centuries of the transatlantic slave trade. The International Labor Organization, a United Nations agency focused on labor rights, recently—and some would say conservatively—raised its worldwide estimate of the number of slaves from 12 million to nearly 21 million human beings, individuals unable to escape conditions of forced labor, bonded labor, slavery, and trafficking. Africa and the Asia-Pacific region together account for the largest number, close to 15 million people, but slavery is epidemic around the world and increasing.

In Sudan, slavery is not a new phenomenon. Intertribal slave raids, Sudanese Arabs enslaving southern tribal peoples for personal use and export, and the lucrative 19th-century European slave trade all played tragic parts in Sudanese history. But in the 20th century, during Sudan’s two scarcely interrupted civil wars, slave raids by northern Arab militia became an especially brutal strategy of the north. Murahaleen, white-robed Arabs armed with Kalashnikovs, swept down from the north on horseback, raiding and burning Dinka and Nuer villages, seizing thousands of women and children, decimating southern Sudanese tribes defenseless against modern weaponry and government-supported rape, slavery, and genocide. With the north’s population predominantly Muslim, and the tribal peoples of the south mostly either animist or Christian, religious divisions and cultural rifts, along with complex historical, agricultural, and environmental factors, including Chevron’s discovery of vast oil reserves in the south in the 1970s and the Sudanese government’s introduction of sharia law in 1983, created unfortunate, if not inevitable, conditions for civil war.

After 50 years of war and six years after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed in 2005, the South Sudanese voted in a historic referendum in January 2011 to secede from Sudan. On July 9, 2011, the Republic of South Sudan, led by President Salva Kiir Mayardit, became the world’s newest sovereign nation. Today, the Islamist president of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, continues to deny the existence of as many as 35,000 South Sudanese slaves who remain in his country, and refuses to cooperate with South Sudanese government representatives who want to restore these people to their tribal homes.

Of the thousands of Dinka and Nuer men, women, and children captured in Sudan’s Murahaleenraids, few have escaped to tell their story.

William Mawwin did break free, and his story begins with his ancestors, generations before his birth, among the Dinka of southern Sudan.

Manyuol Mauwein is the tallest of men, an eight-foot giant. He is also the wealthiest, a tribal chief who owns a vast herd of cattle, thousands, like stars, past counting. He has 50 wives, cattle for 50 more. He has dozens of sons and daughters. During the dry season cattle camp, his family lives in conical mud-walled homes with thatched roofs in his village while Manyuol, with the other men and boys, herds cattle in rich savanna grassland. He sleeps close to his cattle at night. They are his spirit connection to Nhialic, to God, who breathes and moves in all living things.

Like all Dinka men, Manyuol is naked but for an elaborately beaded corset signifying status, his readiness for another marriage. His skin and face are coated with a ghostly white ash made from cattle dung fires. His hair, dyed with cow urine and powdered with ash, is a red-gold color considered to be very beautiful. Manyuol is his father’s name, his grandfather’s name, the name of nine male generations before him and unnumbered generations after him. His bull-name is Mawuein, after the rare brown-and-white color of his chosen bull, his song-ox. He composes songs in praise of Mawuein, strongest and noblest of all his bulls, caresses the beast’s twin curving horns and his belly, and brushes him clean each day with ash. Mawuein’s high, white crescent horns, black tassels swaying from their tips, pierce new stars in the sky as he walks. Raising his arms high, Manyuol imitates the curving horns of Mauwein, his song-ox, as he sings the beauty and number of his cattle, the longevity of his people, the beneficent spirit of Nhialac, of God.

Manyuol Mawuein was born on February 19, 1979, in an army hospital in southern Sudan, the third of six children. His birth name connected him to nine or more generations of Dinka grandfathers. As the largest ethnic group in southern Sudan, the Dinka live from the Bahr el Ghazal region of the Nile basin to the Upper Nile and are a pastoral people, cattle herders during the dry season, which begins in December, and cultivators of peanuts, beans, corn, millet, and other grains during the wet season, which begins in the spring. The tallest people on the continent of Africa, the Dinka often reach seven or more feet in height. While early European explorers called them “ghostly giants,” or “gentle giants,” in the Upper Nile they call themselves jieng and in the Bahr el Ghazal region, mony-jang, “the men of men.” The Dinka are polygamous, though many men have only one wife. A woman can marry the ghost of a male who died in infancy, one of his live relatives standing in for the dead man, and many “ghost fathers” exist among Dinka people. Because of the early influence of British missionaries, many Dinka have converted to Christianity from animist belief. Dressing in cheap, imported Western clothes or the loose-fitting Arab jallabah has largely replaced such traditional practices as wearing beaded corsets or whitening the naked body with ash from cow dung fires, a form of decoration that also protects against malarial mosquitoes and tsetse flies.

In 1982, on the cusp of what would become the second Sudanese civil war, two-year-old Manyuol was critically burned in a home cooking-fire accident, an incident that his family, even today, is uncomfortable talking about. William guesses they feel guilty, particularly his mother, and he knows that among Dinka people, whatever is bad about the past is carefully kept in the past. To discuss or dwell on unhappy memories is impolite, even inappropriate. Because of this, though he still bears scars from this accident on his side and back, William understands that he may never learn the details of what happened to him that day. What he does know is that following several months’ stay in a hospital, he was returned to his parents in the city of Wau. Soon after, his grandmother, wanting to protect him from the coming violence, walked seven days from her village of Ajok to bring Manyuol to live with her. Because of his injuries and young age, he was the most vulnerable of her grandchildren. He would be safer in Ajok, with her, than in the city.

My first memory is walking with Joc, my grandmother, down to the river to get water. A fisherman gave me my first fish to bring home. I used to love to walk, talk, and lie down next to my grandmother. She would always make sure I ate first. I never felt she was a grandmother; she was just like a mother to me. With her, I had a joyful life. I love my grandmother a lot. I think of her every day, and know I can never have that life with her again.

Unable to pay his bills, William dropped out of community college classes to take a job as a night security guard at a bank in Phoenix. Hearing this from his friend Ed, I worried that William would plummet between the economic cracks, his hope of an education sacrificed in the monotonous struggle for survival. One morning, before dawn, I was wakened from a sound sleep by a “voice”—one of the strangest things I have ever experienced, and nearly impossible to describe—but this voice was a command, coming from me, yet not “me,” its directive simple: I MUST pay for William’s schooling, for his tuition and books. Whatever its source, this voice would not be ignored. Calling William that day, I got to the point. Find out how much your tuition and books will cost next semester, and let me know. You need to go back to school, you need to get your degree. Scarcely believing this wild turn of fortune, William quit his job as a night security guard, registered for classes, and, with his tuition and books paid for, would never miss another semester of college. Up to that point, with each low-wage job, he had tried to set aside money for one or two classes at community college, starting with the ESL (English as a Second Language) series. At his airport job, when he had asked for a work schedule to accommodate his class times, he was fired. Each month had become an uphill struggle to pay bills. Somehow, William’s life in America had turned into a futile exercise, his dreams trumped by poverty.

As for me, obeying that voice was one of the most irrational, least practical, and finest things I have ever done in my life.

Soon afterward, William began calling me “Mom.” I found it impossible to reciprocate, to call him “Son.” It felt false, ill fitting. And when he casually mentioned that I might write his story one day, I was politely evasive. Skittish. But this past spring, in a kind of parallel experience to “the voice,” I instinctively, though less mystically, came to feel that the time had come to tell his story. So for three straight weeks, William came to my home to be interviewed. Every afternoon we sat in my back guest room, blinds drawn, the dimness offering a kind of sedative twilight I hoped would help him feel safe. I sat across from him on a small white couch, trying not to feel like some impostoring journalist/psychologist as I asked questions and rapidly wrote down each word of every answer. Hours passed with William stretched out in a deep white chair, talking. His chair, my couch, white and solid in the semidarkness, hardly anchored us. Remembering details of his capture and enslavement, he would sometimes break down and cry, something he tries never to do. Still, each time he left my house he was lighter of step, cheerful, as if, in the neutral sanctuary of that back room, he had literally left more baggage behind.

William began calling me “Mom.” I found it impossible to reciprocate, to call him “Son.”

To get to my house each day, William borrowed his friend’s taxicab; occasionally during our sessions, he had to answer a phone call, his speech switching rapidly from English to Arabic to Dinka, depending on the caller. He kept these exchanges short or, increasingly often, turned off his phone. Together, we let go of the present and moved backward in time; we began with that winter morning when a boy’s childhood, William’s, changed irrevocably.

Simple intimacy sprang up between us during these afternoons. At some indeterminate moment, sitting across from him in that shadowy room as he talked, entrusting me with terrible and sometimes pleasant memories, I began to find it natural, a matter of pride as much as affection, to call him my “son.”

—

They teach you to suffer. Put a huge fear in your heart. The day you got captured is the day you start your job.

On a bright winter morning in February 1985, six-year-old Manyuol accompanies one of his uncles to the marketplace. Hearing gunshots, Manyuol imagines that men must be hunting close by. Two days later, again in the company of his uncle, the boy stares as menwearing long white robes and white headpieces gallop recklessly into the marketplace on horseback. Murahaleen. They seize cattle, children, women, blankets, clothes, mosquito netting, winter supplies. Dust is everywhere, confusion, gunshots, terrified screams. His uncle is shouting, trying to reach Manyuol, but the boy stands very still, hypnotized by all the noise, the excitement, the horses. He has never seen a horse, wants to touch one. When a man is shot in front of him, he thinks the figure lying in the reddening dirt is going to wake up. Suddenly, one of the white-robed men grabs Manyoul and throws him hard across a horse’s back, behind the saddle, tying his arms and legs with rope. Manyuol is one of 70 Dinka boys, girls, and women captured that winter morning by Arab militia. Half will perish before reaching the end of a 15-day forced walk; those who survive will be sold, of less worth than cattle, into slavery.

As William recalled that forced walk, his voice was flat, expressionless. Then it broke, and he stopped to cry.

Sometimes what William relates is remembered in the second person, the “you” providing safe distance, a buffer from overwhelming emotions. When he speaks, his tenses frequently blur. Past and present overlap. Time as a straightforward concept dissolves. William’s accent is heavy; his diction and syntax are unique, cobbled from hybrid, self-taught languages. At times, he uses clinical phrases culled from sociology or psychology classes; often, his grammar is incorrect, his sentences confusing. (In this essay, I have lightly edited some of William’s phrasing for clarity while preserving his meaning as well as his style of speech and transitions from past to present.)

Jotting everything down, I slowly came to realize that there is no proper tense for trauma, no perfect grammar for pain. And when he used the word “skip” for escape, I thought how strange a contradiction that was, using a word most of us associate with play to describe running from captivity. I was jarred each time I heard William, with not a trace of irony, refer to the Arab man who had held him captive as “Master.”

First they shot all the boys and girls who couldn’t walk anymore, the four- and five-year-olds.One soldier ties a little boy to a tree, telling us, “If you can’t walk anymore, this will happen to you.” He shoots the boy, takes a metal rod from the fire, shoves it up the boy’s anus. There was a party that night, the boy still hanging dead from the tree.

Another guy stood in front of all of the kids with an AK-47, ordered them to shut their eyes. “If you open your eyes, a bullet will hit you or you will have to shoot another kid.” So you close your eyes. He fires off the gun in front of you; it might or might not hit you. You jump like a bullet. One little boy is crying, “Mom, mom, help me,” but the mother is tied, bound hands to ankles with a rope.

A young Arab guy with a mustache—he wore a white headscarf, carried a white rope—he grabbed this little girl, started laughing when she tried to push him away. He dragged her behind a tree, tore off her clothes; we were all watching. Her brother, naked, my age, tied up like us, jumped to his feet, started yelling to leave his sister alone. No one said anything. The Arab guy turned, shot the boy three times in the chest. Put holes in his chest. The mother was crying, crying. They taped her mouth shut, and the next day, shot her in the mouth. Her baby kept trying to get milk from the dead mother.

That little boy lay right next to me. He was my age. His foot was jerking, blood was coming out of his mouth and nose, he turned his head and smiled straight into my eyes, died. That little boy is the one person I would never, never, never forget in my life. He is a hero to me.

What did they give you to eat?

Rice with insects in it. They forced you to eat it. It gave you diarrhea.

Sometimes what William relates is remembered in the second person, the “you” providing safe distance, a buffer from overwhelming emotions.

Can you describe the walk?

We walked at night because it was cooler for the cattle, and because we couldn’t tell where we were going. You walk and walk, you get so tired, don’t know where you are.

Did you know any of the women or other children?

Yes. One of the kids was a cousin of mine; he’s still in captivity today.

How did they make all of you walk?

In a straight line, holding a rope, two people tied together. Everyone is naked, you have to sleep on cold ground. If you need to pee, you ask, then everyone has to get up with you. At night you can’t see anything—you might step on a snake, a scorpion, get bitten and die. It happened.

One morning, this three- or four-year-old boy, too little to be tied up with the older kids, wakes up cold, tries to go nearer to the fire everyone is sleeping around, gets shot.

If you are weak, you die. If you smile, you die.

Another boy is shot dead because he is sick, then his mother and sister are killed with a machete, because they are weeping.

If you show emotion, you die.

I kept thinking about my grandmother, thinking my grandmother will come and save me. Somehow she will save me.

You have to save yourself.

By the time we reach Babanusa [a town in western Sudan], maybe 30 kids are alive. Half died or were left, sick, by the road, with no food or water.

Do you ever dream about it?

Every night until I was 17. I still dream sometimes about it.

There was one little girl, only four or five years old, wearing a long blue skirt. They ripped off her skirt, hung it on a tree. She got raped by a lot of men. Afterward she said, “When I die, will you tell my father?” She walked for three days after that, naked, bleeding, until she died, until she was free.

I keep seeing that blue skirt.

At the slave market everyone is naked, sitting on the ground. They test you, look you over. They divide you—women, children, young ladies. If you are related, they separate you. They count you, one by one. Now your name, your identity, is an Arabic number: six women, 30 kids, some girls. The Arab women do the selecting. They are looking for slaves to cook, to clean, do laundry, iron. The older kids are taken first, the eight-to-11-year olds. Then seven to five. Nobody takes children under five unless that child is with a woman or one of the women takes the child to raise as a slave. Girls are valuable for sex. By the age of 15 or 16, a girl will have two or three children by her slave owners, and she will raise them, like her, to be slaves.

This Arab family bought seven of us, five boys and two girls. I ended up with the old man, my master. His name was Ahmed Sulaman Jubar. He picked me because I spoke a little Arabic. To speak Arabic made you more valuable. He named me “Ali,” and I had to recite from the Quran, pray five times a day with him. I had to call him “Dad,” his wife “Mom.” Their children, I was told, were my “brothers and sisters.”

We walked one and a half days more. Then with the old man, two of his sons, and a Dinka woman with her daughter, I walked four days more with all the cattle. Everyone spoke Arabic. I didn’t understand anything. When we got to a temporary house, I ate real food, drank milk. I still don’t know what’s going on. I sit under a tree, fall asleep there. Next day, I’m still there. Two days later, I got my first order—go with one of the master’s sons, take the sheep and goats to get water.

I never sit down to rest until I skip five years later.

You’re beaten, slapped, you don’t understand the language, you have to memorize what they say. For two months they tie your hands and feet every night, you sleep on the ground with the cattle. There is nowhere to go. After that, I got picked to take care of the old man. My duties: be his nurse, companion, walk him to the mosque for prayers. His wife stayed in Babanusa with the children and grandchildren. My master liked staying in the country with his cattle and sheep. When his wife would visit, she was terrible, mean like hell, really, really mean. When she comes, it is the worst time for everybody. She sits there cooking her coffee all day, complaining, yelling, crying.

In the morning I cook, bring his tea, black tea with milk, his bread. I cook the bread, too. I fold his bed. I cook his lunch, usually chicken. I do his laundry, using a bucket with water and soap. Lay his clothes in the sun to dry. Master would pray five times a day, he was really into the Quran. Then I start going to cattle camp, rotating with his youngest son, three months younger than me, the son he loved more than anything. When this son was around, I had to leave, go to cattle camp, get yelled at, beaten. One time, when I lost one of the cows, Ahmad, the fourth son, stabbed me, told me find the cow or he will kill me. After I find it, he still slaps me, beats me, gets really rough.

For four years, I didn’t go anywhere. Master told me: Your parents did not want you, now I’m taking care of you. All this is going to be yours one day. I will find you a wife. These are your brothers. You are part of our family. This will be your special cow. So you feel motivated, work very hard. But it is psychological manipulation. Sweet talk. Mind control.

When I was 10, Master took me with him to Babanusa for the first time. It was Ramadan, so we went to buy stuff and to sell cows, goats, sheep. The city was so beautiful! Master had this beautiful house, a city house. We live in it four days, the four most beautiful days ever. I start asking him, “Why do we live in the jungle with cows, why can’t we live here, in the city?” Why, I ask myself, am I living tied up, with rules? In Babanusa, Master buys me cookies. I had never tasted sweets before. I see cars everywhere, and everywhere I see people looking like me, Dinka people, working for themselves. Before, I thought I was my master’s son or maybe his grandson, but when I see all of these people in the city, especially Dinka people, I get my first idea to skip. Back at camp, my dream becomes Babanusa. I start thinking how I will skip. I behave well so Master will take me with him, back to the city. I dedicate myself to him, be loyal to him. Become his best slave so he will trust me.

Ahmed Jubar takes the boy, Ali, to the market in Babanusa for a second time, to sell cattle and buy supplies. On a third trip, Ali is made to go with Ahmed’s fourth son, Ahmad, the one who had once stabbed and beaten him for losing a cow. Ali works all day, washing and ironing mountains of clothes, taking care of Ahmad’s four children, staying awake all night to watch the cattle, always terrified Ahmad will kill him. Still, he has an extra day in Babanusa with Ahmad and his family, and, at a tea stall, meets an older boy who tells him about an even bigger city, El Obeid. “Babanusa is nothing!” the boy says.

Six months later, Ali, now 11, returns to the tea stall to look for that same boy, but instead meets Chol, a 29-year-old Dinka truck driver. This time, Ali is in Babanusa with three other slave kids he met in cattle camp. These other boys are 15, 13, and 12, all older than Ali. After meeting Chol, the four of them talk about how they might escape captivity on their next trip into the city.

On Ali’s fifth trip, he walks into Babanusa with the other three boys. They find Chol. He buys them food, lets them keep the money they’ve just made from selling cow’s milk. When Ali says he wants to go to El Obeid, Chol answers, “I can get a job for you there, but you have to pay me. I have four trucks leaving tonight with cattle and peanuts. I can take you and your three friends.” Ali gives Chol his milk money, makes sure the other boys have a way out, too. They are all runaway slaves now; anybody who gets caught will be beaten, get a foot chopped off, or be killed. If Ali skips on his own, he knows the other boys will be blamed, punished, possibly killed. He decides he can only leave if he helps them escape too, so he invents a story, telling the boys he will wait in Babanusa overnight, watching the cows, while they go in trucks to other cities to buy more cows and bring them back the next day. Believing him, two of the boys go off in one of Chol’s trucks, and the third goes by himself in a different truck to another city. Like Ali, they have given Chol their money. After they are safely gone, Ali waits until dark to leave with Chol. The boy is shaky, scared. He can’t relax until they reach El Obeid the next afternoon.

I am alive today because of that truck driver. He saved my life trafficking me, taking my money, selling me to another master. There is no help given for free. I was a transaction.

Chol drives to El Obeid, the capital of North Kordofan state, and at 4 the next afternoon delivers Ali to a Muslim family. Ali is astonished to see Chol sitting down and eating with the man of the house, laughing, cussing, using the same plates, drinking from the same cups. The wife brings Ali food, examines him, touches him, seems happy he is there.

He will work seven months for this family and never be paid. Sharing a room with another Dinka slave, a 17-year-old boy called Deng, Ali will find life in El Obeid worse than cattle camp, where at least he could be outdoors, could hunt, fish, and drink cow’s milk. Here, inside this house, there is no escape. He works all the time. The first two months, he has to watch the family’s children, walk them to and from school, do all the washing and ironing. After that, he is made to do everything, all the cleaning, and gets beaten if something is not done right. But a happy respite, even a new name, comes when he meets Father Tarticchio.

Sometimes I walk past this church. I see kids running in a field nearby, falling, shouting, laughing, playing with a ball. I watch them. One day, a priest with gray hair and a white mustache comes up to me. His name, he says, is Father Tarticchio. He speaks Arabic and wears a white robe, a red hat, Sudanese slippers, and uses a stick to walk. I find out that he helps all the street kids, gives them clothing, feeds them, helps them to go to school. When he drives his little white car, some kind of Italian jeep, everybody waves at him. He’s well loved in El Obeid. The day he gives me a green T-shirt with a picture of Bishop Daniel Comboni on it, I start wearing it all the time. [Saint Daniel Comboni was a missionary credited with numerous conversions in Africa in the 19th century.] I start going to Bible study at the church because it is so peaceful. One Sunday, Father Tarticchio baptizes me, gives me a new, Christian name, William. After William Wallace, he says. Who’s that? A Scottish warrior, also called Braveheart.

I start going on Sundays to Father Tarticchio’s church. I think the Communion wafer is food, bread, so every Sunday I go up there and eat it. The explanation of what it is doesn’t make sense to me, but I go up there to be fed. In church, it is peaceful. Nobody slaps you, nobody hurts you, and there’s free food. As a kid, you don’t know anything, you go for the food, the clothes, a bathroom.

I want to play with the kids on the field, but don’t know how. Father Tarticchio makes me a goalkeeper, teaches me how. After that, I sneak out of the house whenever I can to play soccer with the other kids. That was the most beautiful thing ever, playing soccer, being a kid.

—

Chol stops by the house after four months. When Ali, now baptized William, tells him he has not been paid for any of his work, Chol answers, that’s because you have to pay me back for the next two years, my price for getting you out. Either that or I will return you to your master, and he can punish you, kill you, for running away. After Chol leaves, William gets beaten more; now he has to ask permission to leave the house. Deng tells him Chol has been stealing William’s “earned” money all along, and starts to talk about Khartoum, a bigger city than El Obeid. With Deng helping him, William plans how he will skip. He agrees to work for Deng’s cousin in Khartoum for one month, and then he will be free.

As he did with Ahmed Jubar, William puts on a show of loyalty to the family, works even harder. Before walking the kids to school, he puts on extra clothing, drops it off at the cousin’s house. One month later, he tells the wife, “Please, I need to buy some clothes.” Trusting him, she gives him money to go shopping.

You’re poor. Desperate. You’re a slave. You’re naive, too, and want to believe what people tell you. Each person influences you the way he wants, then turns mean. You get used to it. You don’t care anymore. You decide you’re not worth anything. You wonder, who will treat me with honesty and kindness? Who will love me just for who I am? When you are a street kid, you cry and cry and cry, and reach a point where you feel nothing anymore. That protects you. You force yourself to have relations with that person who is bad to you. Emotionless. Forgetting. When you have no family to care for you, you become a person who has already given up on his life, with nothing to lose. When you have nobody, people know it, and they beat you. If you have a family, you are protected. And in Khartoum, everybody can tell if you are Nubian, Dinka, Nuer. They take advantage of you, are cruel because you are poor. Still, God helps you.

William drops his charges off at school and keeps going. When the family realizes he has run off with the money they gave him, they go looking for him. He hides at Deng’s cousin’s place a few days, until he and the cousin take the bus together to Khartoum, a 12-hour ride. In Khartoum, the national capital, William sees a lot of other Dinka people standing around. He thinks the marketplace is huge, beautiful. The next day, he starts working for Deng’s cousin, selling cups of cold drinking water at the market. After two months, he is still selling cups of water, and Deng’s cousin is taking half of his money. Since this is not fair, not the agreement, William leaves. The cousin finds William trying to sell water on his own, beats him up, takes his money, threatens to kill him. William is learning a pattern with people—they act nice at first, then control you with fear and beatings. He starts over, tries hustling for money at the marketplace. Three days later, the cousin finds him, beats and robs him again. So he discovers a different marketplace in the city, and at night he sleeps on church rooftops. He spends his days hanging around warehouses, waiting for work loading trucks. Sometimes he goes door to door offering to wash clothes, clean houses. Work is all he has, a refuge. He takes pride in how well he works, does extra work for free. Now 13, William will live like this for the next five years.

Life on the street has different values. There is no emotion. Work becomes a silent language, and the kid who beats me up today might be my friend tomorrow.

Akec, another street kid, becomes William’s first real friend. Hot tempered but loyal, Akec is quick to defend William in fights. One morning, they are riding a public bus together when government soldiers climb aboard and seize all the boys. They find seven boys, including William and Akec, and later release two who are too young. The soldiers in Khartoum are looking for street kids 16 or 17 and up, to put into military training and then send south to fight their own people. William and Akec are made to get on a bus with the other three boys and are driven toward a training camp hours away. When the bus stops somewhere en route, all the boys jump out and start running. Akec and William hide in a nearby soccer stadium until the soldiers give up looking for them. Catching a public bus back to Khartoum, they are too frightened to go outside for three days, and stop going to the city’s center. They find work with Manyon, an older Dinka man. Sleeping outside his house, they sell things, do construction work, whatever he finds for them to do. They work for Manyon two years before they discover he is cheating them, giving them less than half of the money they have earned. When he figures out they know, Manyon calls the police and accuses Akec and William of stealing from him. The police arrest the boys. Every day in prison, freezing water is thrown on them, and they are beaten with switches. There is no court date, no trial. Seven days later, they are driven to a prison farm several hours outside Khartoum.

At the prison farm, you work 16 hours a day, sleep in this little hut. Ninety percent of prison-farm workers are southern Sudanese, Dinka, some Nubians. Men, women, children, working on this huge, huge farm the size of a city, growing food for Khartoum. You wake at 3 a.m., have to put this light bulb on your head so you can see. By 4 a.m., you’re packing in the dark, loading trucks with vegetables, tomatoes, okra, corn. Every other week, somebody dies from a snake bite. If you die there, people in prison bury you. By 5 or 6 a.m., the trucks leave for the market. Seven days a week, you are in bed by 8 p.m., up working at 3 a.m. After two months we get free, but have no money. We stay working at the farm an extra week to pay for a bus ride to Khartoum. Instead, we decide to keep the money we’ve earned and ride in the farm truck to the city. At the marketplace, we have to unload the truck, wait around all day, then load the truck back up again before we are really free.

But misfortune dogs the boys. On their first day of freedom, they wander into an area of Khartoum where a southern Sudanese man has just run off after killing someone. Akec and William are apprehended and accused of the murder. Sitting in shackles in yet another jail, interrogated, beaten, lashed every night, William and his friend won’t be released until seven months later, when the real murderer is found and arrested. It is May 1997 when they get out, and soon the boys find work with a Dinka man named Wael. They sell used clothes in the market, and Wael pays them and gives them food. He is like a father to them. William remembers Wael as the first person since he was captured, to sit down with him and eat off the same plate.

The one nice thing that happens to you when you are in prison is you get to talk all day long about what you will do when you get out. Who you will be. When I get married, you say, or when I get a job, or what I will eat when I get out, when I become a person. When you have a dream life, a second life, you can forget you’re in prison. Then, when you get free of being accused of killing someone, it becomes like the toughest thing ever. You’re so happy when you get out, have the freedom to start your dream life. The same work you did in prison, you get paid to do. But when Wael gets killed in a car accident, Akec says let’s get out of this city, it’s bad luck here for us. He leaves for Port Sudan. I decide to stay. At least I know where I am, it’s familiar. But after Akec leaves me, I live in a world of darkness. Toward the end of 1997, it seems like everybody is going to Egypt. I meet Majok. He asks me to help him load things onto a truck, I start helping him, we talk. I am his only Dinka worker, but my Dinka is terrible, since I mostly learned it from Akec. I don’t trust Majok. I am afraid, don’t want to tell him my story. After three weeks, he finds me in the market and says, “OK, OK, just work with me, stay here, you’ll get paid.” “I’ve worked for many, many people, and all I got was jail,” I tell him. I don’t want his help. Then Majok’s wife tells me her husband’s story, convinces me he’s a good guy. I go back to working for him. One day I tell Majok I want to go to Egypt. “Egypt? I can get you fake papers to go to Egypt. What do you want to do in Egypt?” “Open my own store, sit in front of it, sell things. I’m tired of the streets. I want a peaceful life.” “I have a store, let me show it to you. I have a house, a family, a store.” “You’re rich,” I say. Majok brings me to his home to live, but I am not comfortable in his nice house. Why? I have no trust in anybody anymore. I cut the leather inside my shoe, make a pocket, keep my money there. A street kid trick, your money lives in your shoe. At night I hide my money in a condensed-milk can, bury it in a hole I’ve dug in the ground, a place people walk by every day, so they won’t suspect. I make money selling water, washing clothes, ironing clothes, cleaning, working at the airport baggage claim, anything. Finally, I can give Majok 1,000 Sudanese pounds, that’s maybe around $200, for a fake passport. I am crying when I give him that money. Later, I will find out he overcharged me. Cheated me.

“Don’t tell anybody you have a passport, don’t tell anybody you are leaving for Egypt,” he says.

I end up staying in Wadi Halfa, hustling to make money for a boat ticket. Every Friday night, the boat leaves for Aswan [in Egypt], so after six days, I go to the place I was supposed to meet this guy at. When I find him, he tells me, “The boat leaves at 5 p.m. Meet me tomorrow at 4 p.m., not 4:01, not 4:05.”

I am there at 3:40.

“Where’s the money?” he asks. He takes my money, smuggles me inside this huge plastic container on the dock. I’m in that container for two hours. It’s so hot, I can’t breathe, I’m sweating. Finally, somebody pushes the container onto the boat; I have to wait one more hour until I hear the boat whistle and can open the container and climb out.

After the boat arrives in Aswan, I give the police guy at immigration my passport and what’s left of my money. He takes the money, nods, stamps the passport. “OK, go ahead.”

I ride the train to Cairo, with maybe five or six hundred other Sudanese guys. It takes 12 hours.

February 22, 1998. I am 19, finally in Cairo. It’s the most beautiful city, crowded. Now I can start my own business, my big dream fulfilled. But where to stay? I know nobody, have no money. What food do I eat?

I find a Catholic church where all the Sudanese go. I am given food and an empty room in exchange for working in the church. It’s hard to find work, so the church helps people. I stay there two months until I get a job working in the back of a shoe store. Three months later, I get fired because I don’t have a visa.

After William is fired from the shoe store for not having a visa—a visa costs money—he goes to the UN office in Cairo and has someone help him fill out an application for a UN identification badge. If he is stopped by police, at least he will have this. Over the next several months, he hustles for money just as he did in Khartoum, until the local Catholic church finds him a second job, this one at a factory that makes car batteries, rubber tires, plastics. He works there one month before he decides he wants to work in the salt mines, digging salt with some of his friends. He goes into the factory to quit, but his boss says he can’t leave until he gets paid for that day’s work. He takes William to a machine he has never operated before, a machine that wraps hot plastic onto giant rolls. When William objects, saying he doesn’t know how to operate the machine, the boss replies, “Figure it out,” and walks off. It is August 31, 1999. Hanging on the wall in front of him, used to measure worker output every 30 minutes and to monitor 10-minute breaks every two hours for the workers, is a large black-and-white factory clock. Because of that clock, William will never forget the time: 12:04 p.m.

Part of my body is still there, in Egypt.

Much of what William told me during those three weeks, sitting in the shadowy back room of my house, was painful for him to remember. But aside from the account of his capture by the Murahaleen, this was the worst of our sessions. His voice dropped as the details of the factory accident emerged in a short, scarcely audible rush.

As William attempts to “figure out” how the machine works, its giant roller snags his right arm and yanks it in. Instinctively, he uses his left hand to try to pull it back out.

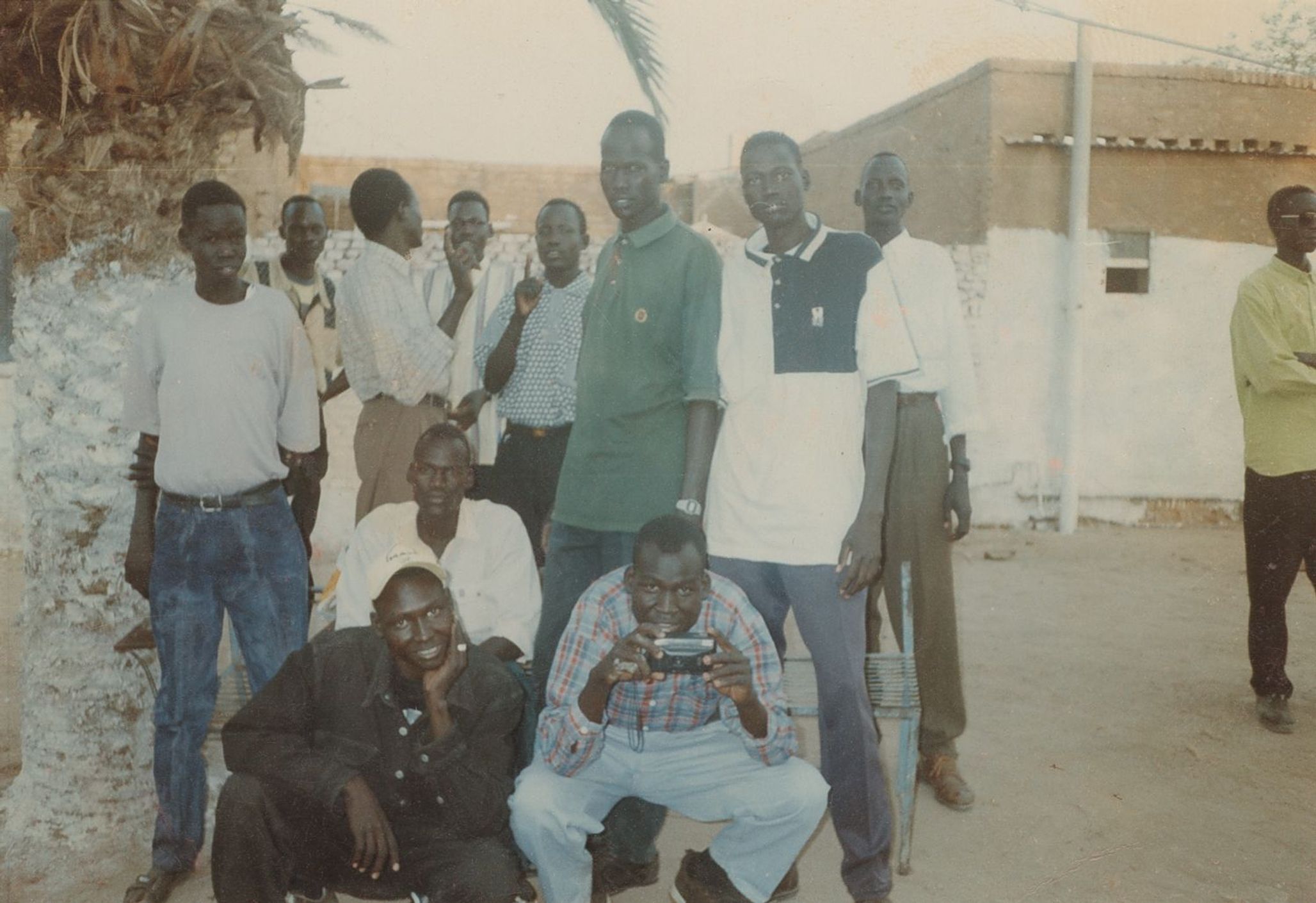

Mawwin hides in a home in Cairo after a 1999 factory accident. Two Sudanese workers run over, stop the machine, and free his mangled right arm and left hand from the machine. They take him to a hospital, but William is not an Egyptian citizen. He is illegal, illegally employed, so no one wants to treat him. His right arm is crushed to bloody pulp. The fingers on his left hand are gone. (Today, William still won’t eat meat, not for moral reasons, but because meat, cooked or uncooked, reminds him of how the flesh of his arm and hand looked that day.)

The Sudanese coworkers spend four hours at the hospital, trying to locate a private doctor willing to perform at-home surgery. Then William becomes frightened. He has heard stories, since verified, of Egyptians killing illegals and selling their organs for profit, so he decides against any surgery outside a hospital. One of the Sudanese takes William’s ID badge to the UN office, tells them what happened. Around 5 p.m., someone from the UN shows up and takes William to a hospital. In surgery that night, the anesthetic doesn’t work. He can see and feel everything. Five days later, the pain is still so terrible, he is taken to another hospital, run by Coptic Christians, for additional surgery, then to a house somewhere in Cairo to recover. At the second hospital, he is given a get-well card, a Bible in Arabic, and a crucifix he will wear every day for years.

The factory owner is hunting for William, wanting to get rid of him as a potential witness. Because of his accident, UN officials have learned that other illegal Sudanese workers are employed at the factory as well, and they plan to investigate. To avert this, the owner fires all of his Sudanese workers two days after William’s accident. The UN never follows up, never investigates employment conditions or the factory owner, so today, apparently no record exists of William’s accident or of the illegal workers. Meanwhile, with his life still in danger, William is moved to a UN “safe” apartment with a security guard posted outside the door.

Now the UN officials in Cairo begin looking for ways to get William quickly out of Egypt. They try relocating him to Norway, then Denmark, then Belgium, but in all three countries, the requisite paperwork takes a minimum of 30 days. At the U.S. Embassy, things move far faster, and within two days William is on a TWA flight out of Cairo with a few clothes, his refugee bag, and some doctor’s papers. During the flight, his arm begins hemorrhaging; he begins to go into shock. The plane makes an emergency landing in Amsterdam, where he will spend the next 28 days in a hospital.

Finally, on January 16, 2000, he is flown to New York City. William is 20 years old.

I am in this big hotel, in a room that looks down on a cemetery. My hands are wrapped up, bandaged. I don’t speak English. I watch the TV, stand at the window, look down at gravestones, snow. My dream was to have my own shop, sit in front of it, sell things.

William arrives at Sky Harbor International Airport at 4 p.m. on Friday, February 16, 2000. A caseworker from the Catholic Charities Refugee Resettlement Program is there to meet him. She drives him to an apartment in Phoenix, shows him a refrigerator filled with food, then leaves. William is left alone in the apartment Friday night, Saturday, Saturday night, Sunday, Sunday night. He can’t use his bandaged hands to eat or to drink, and the skin graft on his leg has become infected. I was in so much pain, it was like being a slave, tied up again. He understands no English, only remembers that during an orientation class in Cairo he had been sternly warned about dangers in America, told never to open the door for any reason, never to speak to strangers, never to stare at anyone.

Exhausted, terrified, sick, he is depending for his survival on a woman whose language he doesn’t speak, a woman who has disappeared. He doesn’t know how to eat most of the food in the refrigerator; it looks too strange to him. When he finds some juice, he drinks that. The caseworker returns on Monday, unlocks the front door, comes in and finds William lying in bed. Thinking he is sick, she drives him to a doctor. But because William speaks only Arabic and Dinka, no one understands what he is trying to tell them. I’m so hungry. I’m in pain. The doctor changes the bandages on his leg, and then the woman takes him to the Refugee Resettlement office. By then, he is shaking all over but can’t tell anyone what is wrong. When he sees a Muslim woman coming down the stairs, he speaks to her in Arabic. Please, tell these people I haven’t eaten in four days. My leg is hurting. Please, I need help.

The woman, a refugee from Iraq, understands, and soon William is fed his first food in days. As they sit in a McDonald’s, the caseworker indicates to the Muslim woman, who has volunteered to come with them—he had plenty of food in his apartment! No, the woman answers, his hands don’t work. He can’t eat. She then feeds him French fries with her fingers, and it is not lost on William that the first person to understand him in his new home, the first person to give him what he needs — nourishment — is a Muslim.

Most of the other Sudanese guys came here as “Lost Boys,” but there is a huge difference between the Lost Boys and me. I was captured when I was six, was a slave, then a street kid. The Lost Boys walked from the jungle to a refugee camp in Kenya, then came to American cities. Our experiences are not the same. It’s really sad—many of them have had trouble, have died in car accidents, are in prison or living on the street, homeless.

William is moved into another apartment, in a plain but neatly kept area of Phoenix. Arcadia Palms is a glaringly white two-story apartment complex, its muddy aqua trim softened by the city’s ubiquitous palm trees and an occasional splash of fuchsia bougainvillea. The complex is filled with refugees, mostly Sudanese. William has two roommates, Malak, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Gurang from Sudan. Malak picks a fight with Gurang, moves out, and soon after is relocated to Nebraska. William will live in that apartment for three years, eventually with five Sudanese roommates, all six young men sharing a one-bedroom apartment that rents for $515 a month. There is a lot of drinking and weed, and three of his roommates get into trouble with the law.

Six months after his arrival in Phoenix, William meets Jim, another person who will change his life. As William told me of this time, he shifted into the past tense, a signal that he would be speaking of yet another loss.

In October 2000, I meet a guy named Achile, the education coordinator for ESL at Catholic Social Services. Achile introduces me to this older gentleman in his fifties or sixties named Jim. Jim had two big trucks, mostly he drove this big Ford diesel pickup. The first time he picked me up at my apartment, he is talking, talking, talking to me. I don’t know what he is saying. He took me to Coco’s on 46th and Thomas for lunch. He orders steak and spinach for himself, fish for me, with blueberries and cake for dessert. He sat and ate, then drove me to the library down the road. He got me a library card and checked out some children’s books. He sat with me in the library until 2 p.m., teaching me to read from those children’s books. The next day, Jim brought some ESL papers to my apartment, then we went to another restaurant on Indian School and 32nd Street. We sat in a far corner and, again, he ordered me fish. We became friends after that second time in the restaurant. For three months, Jim came to my apartment three times a week and drove me to the library to teach me English.

The last time Jim took me out to eat, we went to a really nice fish place on 40th and Campbell. I remember he was drinking water, then started choking, coughing a lot. I worried maybe he was sick.

That was the last time I ever saw Jim. After he dropped me back at my apartment, he said something I didn’t understand, and when he didn’t show up the next time, I tried to find him by calling Achile. Achile told me Jim had moved to New York. “When I come back from my hiking trip next week, I’ll give you his phone number.” Four days later, I learned Achile was dead from a fall.

The world became a dark place.

Jim did so much for me. I couldn’t tell him. Can you imagine? Three times a week for three months to teach you, to feed you for free, and you don’t speak English, so you can’t tell him how you feel?

If Jim is alive, I’d take him to the same restaurants, sit in the same places. “What did you tell me that day? I didn’t understand you then, but now I can tell you what I am feeling.” It’s a silent talk I have over and over in my heart, but I can’t ever tell him. I can’t look in his eyes, at his face. I can’t ever tell him.

Jim is the reason I learned English. I want one day to meet him, to show him: This is my associate’s degree, my bachelor’s degree. Thank you.

I can’t go to that library anymore, where we used to sit with the children’s books.

During one interview session, I asked William what jobs he’d had since coming to Arizona. Stoically, he ticked them off: delivering pizza for Papa John’s and Domino’s, making gum in a candy factory, working in a parking booth at the airport, working as a night security guard in a bank downtown. Every time he applied for a new job, he would be questioned about his disability, asked how could he do the work. “Don’t let my arms intimidate you,” he would answer. “Give me two days, and if it doesn’t work out, tell me. I will respect your opinion.” Since his escape from slavery, since his factory accident, William has only wanted one thing: independence.

In the long run, no matter what, I have to do things for myself. I changed my own tire when my car broke down. Nothing is hard when you put your mind into it. Just focus, relax your mind, and you will do it. It is fear that gets you hurt.

William has a car and a job, and things are almost peaceful for him, when he meets an 18-year-old American girl who likes hanging around the Sudanese refugee guys; when William meets her, he offers to help with some family problems she is having. Soon, she is calling a lot, asking for rides here and there. As he told me about her, I hesitated to press for details. “After a while, we got together,” he simply said. He had been naive, he added, to have gotten involved, though he still carried a photo of her in his wallet.

I wore black every day to show I was dead but still walking around. I started dressing like this in Africa, after I got out of captivity. Wearing white meant a peaceful day, a better day for me. If I wore black and white, mixed, that meant anything could happen, good or bad. I dressed almost always in black, until the day I became a father.

On the last day of September 2003, William is in school, taking an ESL class. A security guard comes in to get him, and he drives to Arrowhead Hospital. He stays all that night and two days more. On October 2, at 1:45 a.m., William’s daughter is born by C-section, and William is there to cut the umbilical cord. Afterward, he goes outside the building, sits down, and cries. He told me that by the time he went back inside the hospital, his whole perspective on life had changed.

William and his girlfriend give the baby a Dinka name, Achol.

Up to then, I told people what they wanted to hear. Kept to myself. I was like a ghost, empty, living day by day. I didn’t care about my life. Today, I have someone to live for, to say I love you, words you never hear before. When somebody calls you “Dad,” you feel so proud.

He stays three days at the hospital, leaving only once to buy some baby clothes and a car seat. On the fifth day, William drives the baby and his girlfriend to her mother’s apartment. When his daughter gets sick and has to go back into the hospital, William quits his job to take care of his new family. He drops out of school. Soon, there are problems with his girlfriend.

Through acquaintances in the Dinka refugee community, Mawwin learned his brother Abey was living in Calgary, Canada. Shown in this 2005 photo taken at Phoenix’s Sky Harbor International Airport, Mawwin prepares to reunite with Abey.

He is living in an apartment with five other Sudanese men, saving money for a place of his own, when the court awards him sole custody of his daughter once he is financially stable. In the meantime, his girlfriend’s aunt and uncle are to take care of the baby. Although William is allowed to see his daughter whenever he wants, it is still hard for him to let her go.

In my apartment, I have a T-shirt that says “Daddy’s Girl” with Achol’s picture on it. I still have the teddy bear I brought to the hospital the day she was born. It stays on her bed in my apartment. Sometimes I sit and hold that teddy bear and try not to think I’m a failure. I tell myself I am a father, and my daughter is the first happiness of my life.

In Dinka, Achol means “reward after long troubles.”

A joy. A happiness.

In North America, the Sudanese refugee network is extensive and strong, deeply reflective of tribal culture. Through it, lost friends and relatives are located and reunited. In 2005, William attends a large Sudanese gathering in Nashville and meets a young man who knew one of William’s brothers, Abey. He says Abey is living in Calgary, Canada. Returning to Phoenix, William calls Abey, and on May 17, 2005, he flies to Calgary with Ed Ashhurst, the filmmaker. Soon after the brothers’ reunion, their relatives in Ajok learn that William is still alive, living in America. When he speaks to his father on the phone for the first time, William does not mention the factory accident in Cairo or his disability. He decides to wait until the day his family sees him, and in December 2009 he is given a miraculous gift—the opportunity to return home. He has been tutoring a student in his math class at Scottsdale Community College, and when the student’s father hears William’s story, he volunteers to pay William’s airfare for a trip to Sudan for Christmas. William has not seen his family for more than 20 years.

On December 28, 2009, I flew to Wau, then drove to Ajok. I arrived home at 3 a.m. I didn’t tell anyone I was coming—I didn’t believe I was there myself. All the trees, the jungle, everything—look different than you remember. The village is not the village I used to know. People look different, grown up, married, with two or three wives and kids. The people I loved, like my grandmother, were mostly all dead. Still, people came out from everywhere and start crying. My mom had moved from Wau back to Ajok, and when she came outside and saw me, she fell to the ground, went unconscious. All these years she believed I was dead.

The first place I went to visit was my grandmother Joc’s grave. She died in 2004. Her house still had my uncle living in it. I went inside to see her old room and slept there my first night. I thought if I could feel her presence, let her know I’m back, it will complete my happiness. It was a huge moment for me at first, then empty. She’s not here, not in her room, my grandmother is dead. Maybe, I think, she’ll see me in the spiritual way.

In June 2010, when charity activist and former NBA basketball star Manute Bol dies in the United States, his family asks if William will escort Manute’s body home for burial. Manute is from Turalei, a Dinka village not far from William’s village of Ajok, and Manute’s father is powerful, well known, “like an emperor or a king among Dinka people,” William explained. Both families know one another and are distantly related by marriage. In Phoenix, after attending a cousin’s graduation at Arizona State University, Manute met with William; they talked and played dominoes. William has a photo of himself with Manute, another of one of Manute’s sisters at her wedding. He agrees to escort Manute’s body home to Turalei, and attends his funeral. Afterward he travels to Cairo, then to Khartoum, where he searches for and, incredibly, locates the family that had owned him as a slave.

The old man, Ahmed Jubar, is dead, but investigating further, William locates Jubar’s fourth son, Ahmad, the one who had stabbed him. William calls Ahmad, says he is in Khartoum and wishes to see the Jubar family again. The two men meet, sit down together, and immediately Ahmad denies that William, as Ali, had ever been his family’s slave. He had been a part of their family, well treated. Why had he run away? If he hadn’t run off, then that — here Ahmad indicates William’s arm and hand — would never have happened. William invents a story to gain Ahmad’s trust, saying that one day in Babanusa, a man had offered him a ride in a car, then taken him away. He hadn’t run away, he had been kidnapped! William says he is now a college student in America, and Ahmad, initially incredulous, soon asks for William’s help in getting his own son into an American college. Uneasily reunited, William and Ahmad travel to Babanusa to see the rest of the family. Every member of the Jubar family, including the old man’s widow, denies William had ever been beaten or mistreated, had ever been a slave. They insist he had been part of their own family, well cared for, until he made the poor choice to run away, or, as William explains to them, had been kidnapped. After he returns to Phoenix, it takes William a long time to process the Jubars’ blatant denial, their collective insistence that he had never been a slave, that he had never been harmed by any one of them.

I wanted to find the old man and forgive him. Without him capturing me, I would not be in America. So a bad thing, being captured, taken from my village, turned to a good thing. I wanted to show that family who I had become, how I had changed my name from Ali to William, how I live in the West now. I wanted them to see the difference between who I was with them—a slave—and who I am today.

In January 2011, William and Ed fly for a third time from Phoenix to Ajok so that William can vote in the referendum on an independent southern Sudan. And in early July, William returns with Ed, to celebrate the birth of the Republic of South Sudan. The new Government of South Sudan (GOSS) has extended an invitation to a number of Sudanese college students living in America, William among them, to help host the ceremonies in Juba, the new state’s capital. On his first day in Juba, wearing an official GOSS press badge, he drives to the airport to greet and escort UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon, the vice president of Cuba, Esteban Lazo, and the president of Zimbabwe, the infamous Robert Mugabe. The next day, William returns to the airport to greet Susan Rice, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. William refuses to greet or to escort Omar al-Bashir, the president of Sudan. At a news conference later that day in the presidential palace, William shakes hands with Salva Kiir Mayardit, the first president of South Sudan. And on July 9, 2011, wearing the red jacket he bought in America just for this occasion, William watches as the black, red, green, and blue South Sudanese flag is raised for the first time. He listens as President Mayardit, Ambassador Rice, the British foreign secretary, William Hague, and many others speak, even al-Bashir. Later, William will say it was the best, happiest day of his life, the day of independence for his new country, the Republic of South Sudan.

In Juba, William is offered a number of promising jobs. Because of his fluency in English and his education — hard won but hardly elite, at least in the United States — he is a valuable asset to a new nation with a 27 percent literacy rate, a 51 percent poverty rate, and a population that is 83 percent rural. The national government offers him a job overseeing the building of roads and infrastructure; the UN wants to hire him to assist people with disabilities in South Sudan, and the governor of Wau is interested in having him help disabled schoolchildren. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (the current ruling political party in South Sudan, headquartered in Juba) along with other political parties in Juba, are also interested in his potential contribution to the fledgling republic. And William is clear about his aspirations to set a new example for a culture that sees no value in disability. He wants to set an example by his education, and his refusal to let disability limit him. The job offers are flattering, even tempting, but he turns each one down, explaining that he needs to return to America and earn his college degree before he can help his country in the ways he dreams of. Beyond agricultural studies, William wants to work in education and hopes one day to be a role model for Sudanese children disabled by war — an inspiration, perhaps, for all children.

A good thing about Dinka people, they teach a child when he is very young what his name is, what his father’s name is, his grandfather’s, all the way back to the 10 generations. So if he ever gets lost, he can say who he is, people will know, and they will return him. And just by the name, people will know what tribe, what area you are from.

Sometimes, whether he is in Sudan or America, people ask him why he didn’t return to his family’s village after he escaped captivity. Patiently, William answers that he was a runaway slave. Someone’s property. People would hunt for him; it was too dangerous to try to go home. Also, as a captive, he had been forced to walk at night, so he would have had no idea what direction to go in, where home even was.

And sometimes, though he rarely speaks of it or asks for help, people ask him about his disability.

People treat you differently when you have a disability. I don’t blame them. When they ask how it happened or what happened, I have two different answers. The first answer I just say, “An accident.” Then they don’t ask any more about it. The second answer I say, “It’s a long story.” And they drop it.

With my family, my disability makes me nervous. I left when I was six years old, lose my arm and my fingers, then I go back. It’s not hurting me because I’ve been dealing with it for so many years—what is it, 12, 13 years now? Since I was 19 years old. But when I go home, I’m handicapped. My mom’s seeing me, my dad’s seeing me, my other grandmother’s seeing me, a lot of the rest of the people are seeing me, and there are a lot of tears, crying, sadness. It’s hard for them. I’m nervous, seeing my family so sad. And it’s Dinka culture, so they try to please me. I wake up, do everything I know how to do for myself, but they’re right there, trying to do everything for me because I’m handicapped. I start to feel, oh, I didn’t see I was handicapped before, but now with them all trying to be there, doing this and this and this for me, I feel I am handicapped even more.

When my daughter first asked about my arm and my hand, what happened to me, I told her about my factory accident in Cairo. “I’m sorry, Daddy. I love you,” she said, then hugged me for a long time. It hit me really hard then, that my daughter loves me so much.

A lot of people in Sudan are disabled because of the war. Since I’m disabled too, I understand their needs.

William Mawwin came into in my life in 2005, sitting, unobserved, beneath a tree in my backyard during a party. When he calls me “Mom” now, I am strong enough, changed enough, trusting enough, to answer with “Son.” The early doubts I had about this stranger’s motives—was his loyalty feigned or genuine?—have gone. William long ago proved his credibility, his integrity, to me. My two daughters, initially baffled, annoyed by the idea of a grown “brother,” a stranger they did not know and did not choose, are quick and proud to call William their brother. He is a member of our family, and when we celebrate birthdays, weddings, holidays—none of these occasions feel complete without him. He attends events I am involved in and has spoken to students in my classes. A charismatic speaker, he tells his story without embellishment or self-pity. I have watched professors and students alike pay rapt attention, then ask William questions with tears in their eyes. Self-reliant, William rarely complains or asks for anything, but if he does, if he needs money for some unexpected or extra expense, I know the request comes with difficulty, that he hates asking and has exhausted every other possibility. At times, he expresses anger and disillusionment over a local nonprofit organization that invited him to speak more than 20 times on its behalf between 2003 and 2011. He raised money for the organization at these speaking engagements, yet was paid almost nothing, and the $500 scholarship he had been assured he would receive as compensation was never awarded to him. It is an old pattern, being cheated of what he is owed, bitterly reminiscent of his life as a slave. Yet if anyone in my family needs William, he will find his way to that person, without a car, without money—invariably, loyally, he shows up.

Our family celebrated Thanksgiving as I was in the midst of writing William’s story. After dinner, I asked him if I might try taking a few photographs of him specifically for this article. I imagined one photo of his scarred upper back, another of him facing the camera, wearing his dress shirt and russet corduroy jacket. I was a bit unsure, a little embarrassed to ask, but when I did, William good-naturedly agreed. In front of my older daughter, my son-in-law, and me, he took his jacket and shirt off. Half naked, he turned boyish, joking around, mugging for the camera. When I asked about the long, faded scar in the center of his chest, he answered that it was from a knife blade that had been heated in a fire, then held against his chest. “People ask if I’ve had heart surgery when they see that scar,” he laughed.

The lighting was wrong in the room, the photos turned out badly, and the whole idea, I realized, after William had gone home, had been a bit melodramatic anyway. As my daughter and I worked quietly in the kitchen, cleaning up, washing and putting away dishes, she stopped suddenly.

“Now I know how he gets dressed. I’ve always wondered.”

“What do you mean?”

“Mom, didn’t you see? To do the buttons on his shirt, to get dressed, William uses his teeth.”

Surrounded by the remnants of a holiday feast, its store-bought bounty, we stood a moment, saying nothing.

My life, it teaches me to watch, to not get upset or excited too much. When I’m upset, I’m only making it worse. I have to breathe every day, I have to think of the next day. If I get too excited, there is no one to rescue me, I am on my own. I have to think what is good and bad. I have to watch. Take my time. Imitate people when they aren’t watching. I learned that good people can turn to bad people. When someone wants something from you, they treat you nice until they get what they want. That is the reality, but I don’t want to treat people like that. I appreciate all the people who did good things to me. I even appreciate the ones who did bad things to me. I really wish I could sit down with every one of those people, show them my appreciation, show forgiveness. I wish I could do that.

William Mawwin is now 34 years old. Named Manyuol at birth, renamed Ali by his Arab master, baptized William after a 14th-century Scottish warrior by an Italian priest, William speaks Dinka, Arabic, and English. He became an American citizen on July 17, 2009, began to attend Scottsdale Community College full-time, and in 2010 began receiving assistance in the form of federal disability payments and federal Pell grants. On May 10, 2013, William received his associate’s degree in business from Scottsdale Community College, and this fall he will begin his junior year at Arizona State University, working toward a B.S. degree in global agribusiness. He intends to use his American education to return and help the government and the people of South Sudan.

After his graduation, William Mawwin told me he was going to reclaim his birth name, inherited from nine generations of grandfathers and tribal chiefs. One of these grandfathers, Manyuol Mauwein, eight feet tall and blessed with thousands of cattle, many wives, dozens of children, remains a legendary figure among the Dinka.

Having survived slavery, imprisonment, amputation, and nearly 30 years of exile, William, no longer a male child believed dead, no longer a “ghost father,” now knows who he is: a direct descendent of Dinka chiefs, generations of men named Manyuol, whose tribal leadership was marked by gentleness, dignity, and a just, visionary wisdom.

William — Manyuol Mauwein — has come home.

—

Melissa Pritchard is the author of eight award-winning books of fiction and a biography. A ninth book, Palmerino, will be published by Bellevue Literary Press in 2014. A professor of English at Arizona State University, she is the founder of the Ashton Goodman Fund, which benefits the Afghan Women’s Writing Project.

Filmmakers Ed and Carlos Ashhurst are completing a documentary feature on William Mawwin's efforts to expose the slave trade in Sudan. The film will be released in May 2014.