Summer 2015

What 18 focus groups in the former USSR taught us about America’s image problems

After talking with dozens of people in Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan, two contradictory, prevailing themes emerge about the United States.

THE UNITED STATES has a major public relations problem in former Soviet countries. Not only in Russia, but in Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and even Ukraine, ordinary people see the U.S. as an arrogant, hegemonic superpower that meddles in the affairs of other countries in a cynical pursuit of its own interests — perceptions that dovetail with the Russian government’s official critiques of the United States, which may explain the success of these particular memes. At the same time, citizens of these countries respect and admire American economic power, technology, culture, and, to some extent, its political institutions. This dual-sided picture — often obscured by crude survey-based measures of views of America in post-Soviet nations — emerged from 18 focus groups we conducted in Russia, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine between April and August 2014.

To restore American soft power in the region, the United States should reduce direct support for civil society organizations in former Soviet countries and others that lack intrinsic demand for civic engagement. American financing of these organizations has played into the hands of authoritarian leaders who portray such backing as evidence of American interference, hurting the reputations of both the U.S. and the local NGOs that receive American funds. Instead, American policies should emphasize programs which spread and deepen knowledge and appreciation of American institutions — more exchanges of people, ideas, and cultural products.

American Democracy Assistance, and the Russian Critique

Since the late 1980s, the United States has sought to promote democracy in semi-authoritarian and transition countries by providing financial and technical support to NGOs that pursue civic and political causes, election monitoring efforts, and oppositional political parties. These policies appeared to bear fruit when popular democratic movements helped overthrow dictators in Chile, Nicaragua, and Serbia, and with the successful “color revolutions” in Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, and Ukraine.

The approach has been less successful in Russia, and has contributed to a general curdling of U.S.-Russian relations. In 2009, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that from 2006-2008, federal agencies spent nearly $100 million on democracy promotion in Russia — much of it in the form of funding for “civil society programs” — making Russia the sixth-largest recipient of U.S. spending for that purpose.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s October 26, 2014, speech at the “Valdai” discussion club received worldwide attention for its condemnation of American foreign policy. Putin claimed the United States actively interferes in the affairs of other countries, cynically foments “color revolutions,” and even supports Islamic terrorists under the guise of promoting “peace, prosperity, progress, growth, and democracy,” all in order to preserve its dominant, hegemonic position in a “unipolar” world. The level of vitriol in Putin’s Valdai speech may be unprecedented, but its content is not.

If Russian critiques of the U.S. hold sway, it poses a major threat to American “soft power” in former Soviet states.

As Thomas Carothers observed in a 2006 Foreign Affairs article, Putin has been leading a “backlash” campaign against American democracy assistance since 2005, when Russian officials began labeling domestic human rights NGOs with foreign funding as a traitorous “fifth column,” a now-standard moniker in official speeches and pro-Kremlin Russian media. In a February 2007 speech in Munich, Putin sounded the themes of unipolarity, U.S. hypocrisy in preaching democracy and human rights, and its interference in Russia’s sovereign affairs. After spontaneous protests arose in Russia following allegations of widespread fraud in the country’s December 2011 parliamentary elections, Putin blamed the revolts on U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, charging that she sent “a signal” to certain “actors” in Russia — a threatening specter of American menace which became a prominent theme throughout Putin’s 2012 presidential campaign. In his March 18, 2014, address on the “reunification” of Russia and Crimea, Putin again labeled those who oppose his policies as a “fifth column, [a] disparate bunch of national traitors” supported by foreign interests.

Although its main audience has been domestic, the Russian government has actively sought to export this message, investing massive resources in its international “RT” (formerly Russia Today) media network, which now can reach 600 million people worldwide with broadcasts in multiple languages. Domestic Russian media broadcasts are ubiquitous in other former Soviet republics, offering a steady diet of reports dramatizing United States interference in other countries’ internal affairs, highlighting problems in America, and portraying developments such as the collapse of the Yanukovych government in Ukraine, the downing of flight MH-17, and combat in southeastern Ukraine as direct results of U.S. actions.

Rhetoric aside, the Russian government has passed a series of laws tightening the screws on foreign-funded political NGOs; requirements that they register as “foreign agents,” with connotations that they are spying for foreign governments, are just one recent example. The influence of Russia’s campaign is evident in copycat legislation enacted in Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan, Yanukovych’s Ukraine, and elsewhere, which has cracked down on foreign-funded NGOs, domestic protesters, and oppositional groups.

In sum, Putin and his associates have put forward a concerted, sustained critique of American democracy assistance for nearly a decade, threatening not only to undermine efforts at democracy promotion, but also to tarnish the broader image of the United States. If the Russian critique holds sway, it poses a significant threat to American “soft power” in former Soviet republics, much to the long-term detriment of United States foreign policy.

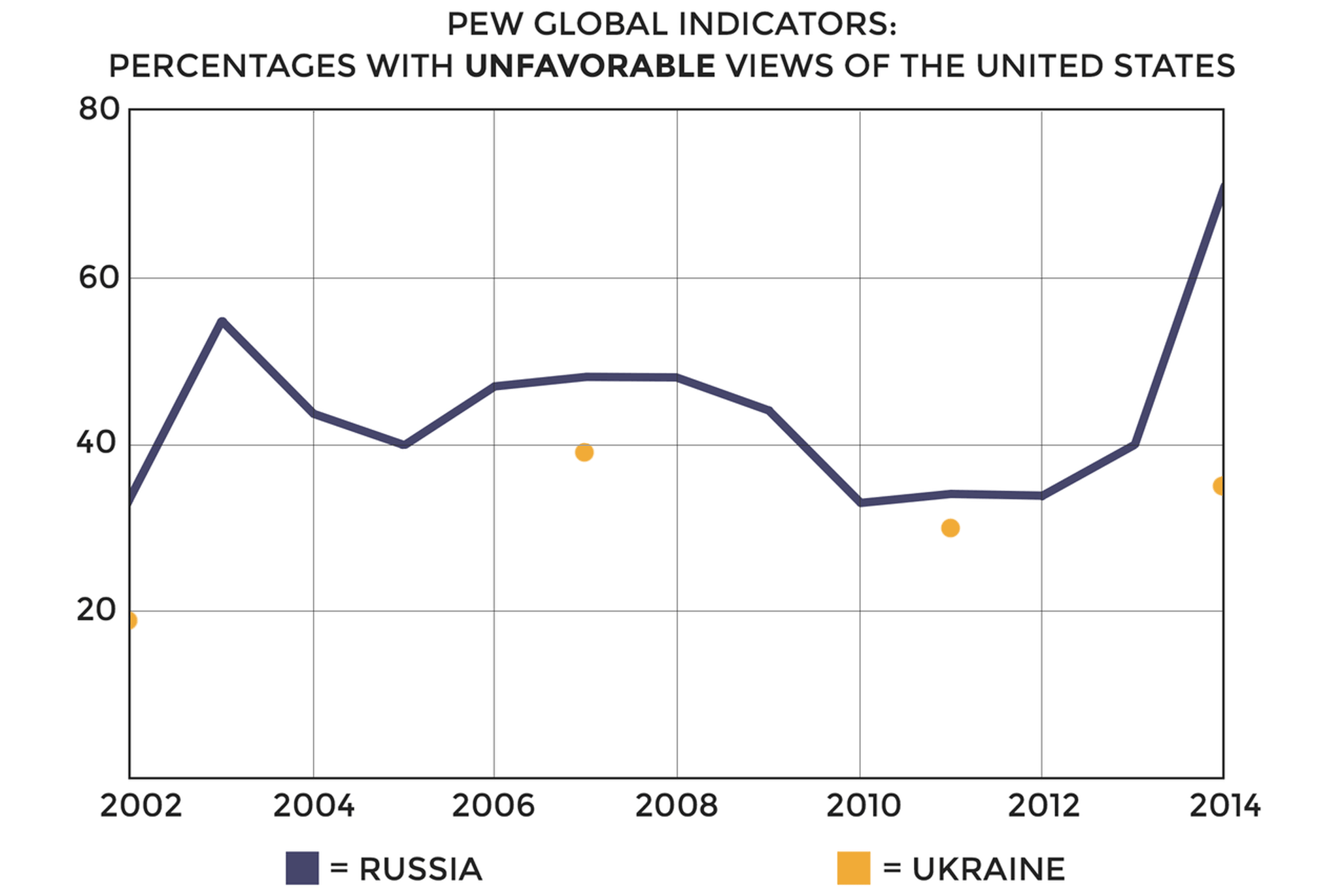

There has been virtually no empirical research into whether the populations in these countries actually buy the Russian critique. Survey researchers regularly investigate how Russians feel toward the United States, and similar studies have been done in Ukraine. Predictably, Russian public opinion on the United States has fluctuated; negative views surged following the Iraq invasion and, even more so, in the last year, after the Crimea takeover and hostilities with Ukraine.

But apart from these flag-rallying, event-driven episodes, generally less than half of the Russian population has expressed unfavorable views of the United States. The more sporadic negative numbers in Ukraine have been consistently below those for Russia, but in 2014, about one-third of Ukrainians polled were unfavorable towards the United States, despite U.S. support for the Ukrainian government and economic sanctions against Russia.

While informative, the survey data offer limited insight into the traction of Russian government arguments about U.S. democracy assistance. By their nature, surveys reduce nuanced and ambivalent attitudes to a single number, thereby potentially masking the underlying complexity of views. Anti-American sentiment within Russia increased modestly in 2006, just after Putin and company launched the Russian critique of American democracy assistance, but temporal coincidence does not demonstrate a causal relationship. Moreover, the waning of negative views in 2009 suggests other factors are at work. Without asking why Russians have negative views we cannot really say what is driving them.

Methodology

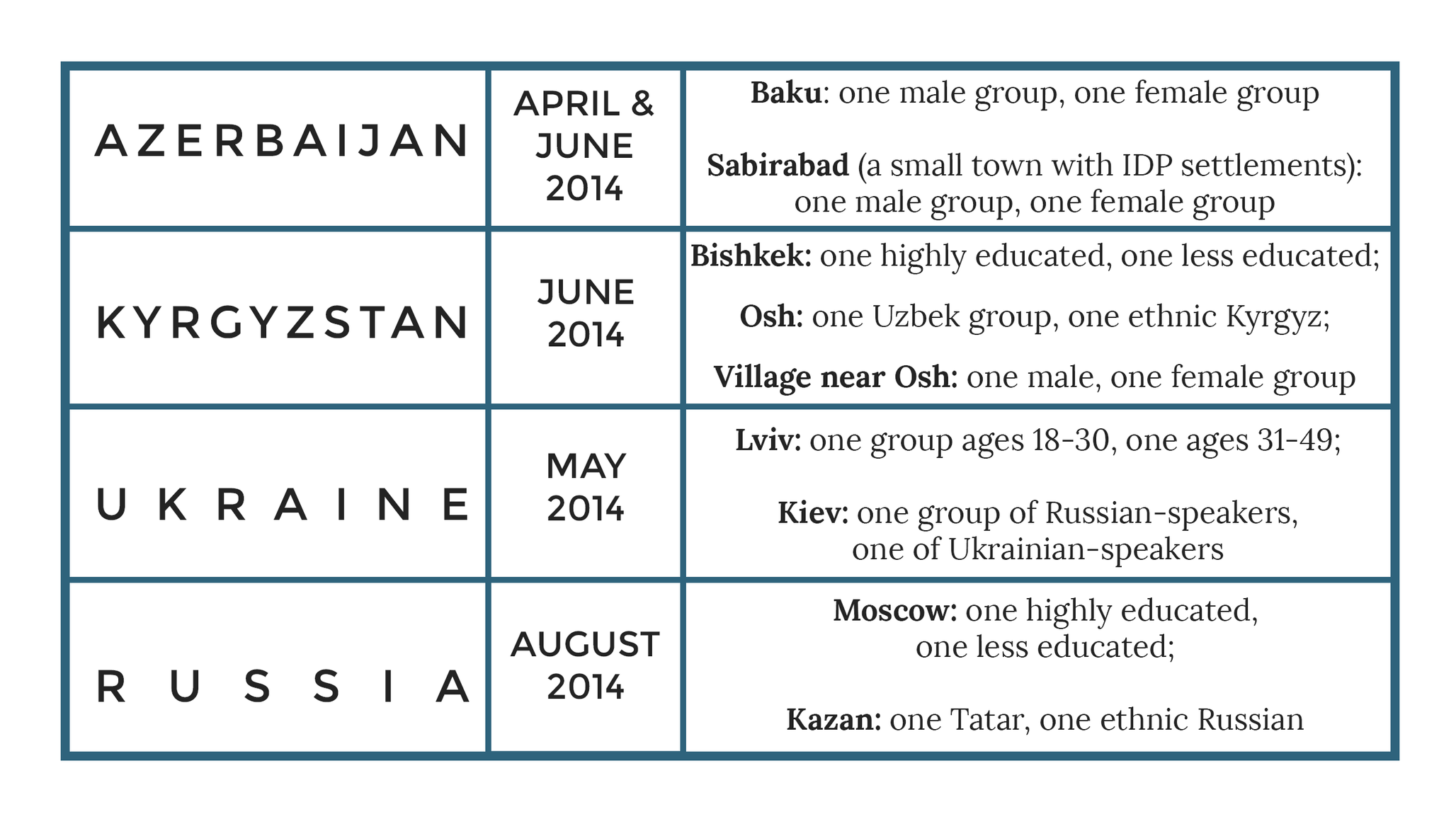

TO FIND OUT HOW AMERICA IS PERCEIVED IN EURASIA, we worked with local research organizations to conduct 18 focus groups in Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan from April to August 2014. We developed the focus group guides and observed all the groups, save for two in Sabirabad, Azerbaijan, which we could not attend due to logistical and political issues. Our local partners recruited participants (all of whom were 18-49 years old), provided native-speaking moderators, and the translated the transcripts. Each group included 8-10 participants. The timing, location, and composition of the groups were as follows:

These focus groups’ small and selective samples mean that they are not necessarily representative of larger public opinion, but they provide substantially more detail than mass surveys about the reasoning behind people’s attitudes, and the language they spontaneously use to express their opinions. While journalistic interviews often seek a balance of views on an issue (or else push a particular position), focus groups obtain an objective sense of how a random selection of individuals think about the topics discussed. By comparing groups within and between countries, one can ascertain whether specific logics and narratives represent common themes or idiosyncratic expressions.

Two contradictory themes regarding the United States emerged in the groups: one, skepticism and outright hostility toward American foreign policies and actions in the world; two, respect and admiration for American economic power, technology, culture, and, to some extent, political institutions. The rationales supporting the first theme testify to the resonance of the Russian critique of American democracy promotion, while the second theme suggests that despite such efforts, what might be called the “American way of life” still holds considerable appeal.

Support for the Russian Critique

NOT SURPRISINGLY, the anti-American theme was most pronounced in the Russian groups. With near unanimity, Russian participants voiced negative views of the United States that echo elements of their government’s critique.

They characterized America as an aggressive, arrogant superpower that seeks to impose its will on the world, eliminate any competition, and specifically, pressure Russia:

“Americans want to be lords of the world, and Russia now stands in their way.” (Moscow, university educated)

“[The Americans] think that they are always right and they won’t consider any other opinions; they do whatever suits them.” (Moscow, university educated)

In particular, many blamed America for the Ukrainian conflict, claiming, for example, that America caused it in order to profit from arms sales or to install its military technology along Russia’s border (Kazan, Tatars). Several asserted that American soldiers were actually engaged in combat operations in Ukraine, and one insisted that the Americans shot down flight MH-17 in a botched attempt to target Putin’s plane.

America, some said, uses money and power to turn its allies against Russia:

“America is our enemy for life, our main troublemaker.” (Moscow, less educated)

“‘The Party said we need it, the Komsomol answered: it’s done!’ [a reference to a Soviet-era slogan] It’s the same thing [with America and the EU]. America controls everyone because they apparently depend on America. … [America] probably pays [the Europeans], probably promises them some kind of property in turn for cooperating.” (Moscow, less educated)

America fears Russia as a competitor:

“Well, it’s as if we are helping ourselves to a lot [by taking Crimea], and the Americans think that they are the only ones who can do that. And it’s as if Russia showed her teeth, that’s why [they imposed sanctions]. … They think we might take something else in the future. If we took a piece of Ukraine, maybe we will take something else, right?” (Kazan, ethnic Russians)

Yet, America also seems to crave Russia’s resources:

“[They see us as] a tasty morsel, which they want to seize and divide among themselves. We have enormous territory, one-sixth of the earth’s mass, and 140 million people. And so they’re sharpening their knives for our untold riches. They want to turn us into cattle and seize our territory. And whatever we do, sooner or later they will attack, it seems to me. Whatever we do, there will be war. They cannot resist such a tasty morsel.” (Kazan, ethnic Russians)

No doubt reflecting official statements, some participants specifically singled out America’s purported efforts to undermine Russia by sponsoring political NGOs, a “fifth column”:

“I heard that [America] sends people here, supplies them with money in order to cause an uprising or something like that. Like in Syria, where Americans purposely sent in people under false pretenses, as if they were going to work there or something, and those people encouraged an uprising against the government, or a coup. And in our country, the ‘Bolotnaya’ protests were the same thing, most likely. They provide them with money, big money, in order to spur them on.” (Kazan, Tatars)

“[Foreign-funded NGOs] simply play the role of a fifth column. They are all Western supported, and that’s it. Take, for example, the well-known George Soros Fund. What are non-governmental organizations and what are they doing here? They have completely transparent and concrete goals: formation of civil society, providing help in the area of medical care, getting to know future doctors, in the realm of education, humanitarian aid, like we had in the 1990s with ‘Bush’s legs’ [a reference to the chicken legs imported by United States during the first Bush administration]. But in fact these non-governmental organizations under this guise attempt to sow pseudo-values that are intrinsically alien to an ethnic Russian person, starting with hamburgers and Coca-Cola and ending with computer games and films about all kinds of scumbags.” (Moscow, less educated)

The breadth of anti-American sentiment expressed confirms the survey findings that both support for Putin’s policies and hostility toward the United States are at all-time highs in Russia. But the focus groups add important nuances to the picture obtained from polls. The passion and emotion that Russian participants expressed in regard to the United States were striking, and contrast starkly to the bored and detached tenor of discussions of political topics in past focus groups we have conducted in the country. Had participants merely been parroting official propaganda, it is unlikely the discussions would have been so heated.

Yet, Russians’ views of the United States are more complex than pure condemnation. The same groups also expressed admiration for America’s economic achievements, democracy, high living standards, and American films, music, and television shows. “I have nothing against the American people, only against the American government,” said one participant in the less-educated focus group in Moscow. It was a common sentiment.

Antipathy toward American policies is apparently not severe enough to distort views of the American people. Participants allowed, either explicitly or tacitly, that both sides in the conflict present distorted information about the other. “[T]hey brainwash people there too, just like here,” said a participant in the less-educated panel in Moscow. “After all, how do we know all this? Where do we learn about the political situation? From newspapers, from television. That is, we believe the information that is served up to us.”

Such acknowledgments that their own government manipulates information to suit its purpose indicate an underlying unease, belied by the evident conviction with which the Russian participants toed the official line.

AMERICAN POLICYMAKERS who expect Ukraine’s population to support the U.S.’s foreign policies as thanks for its efforts to counter Russian actions in Ukraine will be disappointed. Although the Ukrainian groups, which were conducted in areas where anti-Russian sentiments predominate, did not express the same hostility toward America as heard in the Russian groups, they voiced ample skepticism about America’s motives in foreign affairs, and disappointment in the extent of support for Ukraine:

“[America] is just another empire. We don’t know much about either the Russian empire or the U.S.A., but they chose Ukraine as a point of conflict where they can fight it out to show who is ‘cooler,’ in a word.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“It seems like they absolutely don’t need us for anything, taking into account that for this whole period they gave us no help. … That is, they gave us something, but it was too little, too late, absolutely nothing. Even those sanctions took so much time and were only implemented after so many people were killed — that all shows that they just don’t need us.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“They prioritize themselves, what is good for them in the first place.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“I feel neutral toward the United States. In essence, they don’t have anything special for Ukraine.” (Lviv, over 30)

Participant 1: “Their basic policy is to make money. And they, for the most part, pretend to help Ukraine, but above all, they only look at their own interests.”

Participant 2: “Well, every country looks after its own interests.”

Participant 1: “They deceived Ukraine, let’s say; abandoned [us].” (Lviv, over 30)

On the other hand, the Ukrainian groups discussed at length the second overarching theme: admiration for the American way of life. They praised America’s respect for laws and human rights and its “social protections”:

“If you are a citizen of the United States then you truly have rights, and they are respected, not like in Ukraine.” (Lviv, over 30)

“[In the U.S.], the laws are observed more.” (Lviv, over 30)

“We have been talking a lot about social protections. I have very close friends who live there, and they are ecstatic about life there. They even went driving in the desert and their car broke down — in the naked, empty desert. Even there, they made one phone call and in five-to-ten minutes, a tow truck showed up. They have massively high taxes, which makes their hearts bleed, but they get something in return: social protections, plus work. That means the chance to travel, rent housing. They rent and buy, they are confident in tomorrow.” (Kiev, Russian-speakers)

“Medical care, education, the legal system — everything is on a high level there.” (Kiev, Russian-speakers)

American institutions encourage business and hard work:

“I have a friend who is a programmer who lived there for two years. He said it is the only country in the world where, in his view, a person’s talent is truly valued. … Everything is set up so that if a person is talented and hardworking, then the state in no way interferes with their self-realization.” (Kiev, Ukrainian speakers)

“It is heaven on earth there — except you have to work hard.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“Conditions for doing business are much easier.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“You have to work hard there.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“Our people who migrate there and work make a lot, and they tend to do better than the people who have lived there all their lives, because our people have a lot of internal resources and are used to hard work.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

America’s political institutions are more effective and less corrupt than Ukraine’s:

“The president there has a lot of power, and somehow — if we exclude Bush, the previous president — they get relatively intellectual people in that position. Everyone said that Clinton was a fool, but under Clinton, they had the strongest economy in the last 30 or 40 years. And in any case, their president is not a twice-convicted criminal, an idiot who cannot say two words without being laughed at. He is a smart person.” (Kiev, Russian-speakers)

“We live in a kind of information vacuum. They have thrown all kinds of dirt at America — mafia, drugs, and so on. If we compare how much they drink in Russia, then there are not so many drug addicts [in America]. They are on a different level there. People who have lived there and come back here tell me how the police behave there. For example, they will give directions, help you find things. That sort of thing. Here when you see a police uniform you immediately try to hide.” (Kiev, Russian-speakers)

“There, they have courts and juries that decide independently of any ‘instruction’ whether [the accused is] guilty or not-guilty.” (Lviv, over 30)

Even in Ukraine, America’s most potent form of soft power is not its effort to counter Russian aggression, but instead, America’s political, economic, and cultural institutions. The logical conclusion is that the U.S. can more effectively build a positive image by focusing attention on its way of life rather than its foreign policy.

Not everyone agreed, but some Ukrainian participants also touted the American “mentality”:

Participant 1: “[I admire] their humanity, the fact that they never just walk by [someone in need]. If you have a misfortune or some bad luck, they will help you; they will even take someone into their home and help them get set up; that’s how they are.”

Participant 2: “I think it’s not actually like that; it’s ‘everyone for themselves’ there.”

Participant 1: “Well excuse me, but you have never been there.” (Kiev, Ukrainian speakers)

“They have democratic values, that’s generally their main priority.” (Lviv, 30 and under)

“[I like their] tolerance and their mentality. There, every American is a patriot in the depths of his soul. Even black drug dealers from the ghetto will take up arms to fight for America. They are patriotic.” (Kiev, Russian speakers)

Despite America’s support for Ukraine in its conflict with Russia, the focus group participants endorsed America’s institutions more than its foreign policies. If even in Ukraine, the most potent weapons in America’s soft power arsenal are not its efforts to counter Russian aggression or to spread democracy, but instead, America’s political, economic, and cultural institutions, the logical conclusion is that the U.S. can more effectively build a positive image by focusing attention on its way of life rather than its foreign policies, which include democracy promotion efforts.

Ukrainians expressed concern about possible American meddling in domestic Ukrainian politics:

“Ukraine needs a partner, a strong partner, because we are completely defenseless. But the main thing is that this partner who helps us doesn’t then try to interfere in our personal internal affairs. That they don’t, you know, say ‘we paid for you, so now dance with us.’ If they are helping us only out of pure good will, then thanks. But if it is only under certain conditions, then we have to be careful.” (Kiev, Russian speakers)

“There is a lot about the U.S.A. I view positively; I just don’t want them to interfere in our internal or foreign policy.” (Kiev, Russian speakers)

These suspicions may have been provoked by video clips showing U.S. officials discussing their preferred candidates among Ukrainian opposition figures. To allay such fears, the United States should avoid providing direct financial support for Ukrainian political NGOs or parties, which could easily be perceived as meddling in Ukraine’s internal affairs.

BOTH OVERARCHING THEMES about the United States were evident in the Azerbaijan focus groups. The only point made in the two all-female groups was admiration for the advantages of the American education system, economy, political system, and standards of living; nobody mentioned American foreign policies. The male groups were decidedly more mixed, often noting America’s military might, successful economy, and democracy, but also striking a negative note about democracy promotion specifically:

“I have not been to the States, but I follow mass media, and realize that there is democracy there, unlike many Muslim countries. A historical moment in America was they elected a black president. Of course it is an indicator of a high level of democracy. But the U.S.A. is democratic for itself, not for other countries. It is all in words; in reality, they will never do what local people are supposed to do for themselves. They will not build democracy.” (Baku, men)

“If our education and health care systems were similar to American systems, it would be really good for our country. At least people there know their rights very well, police know their rights and duties very well. There is mutual understanding. If our citizens were aware of their rights like Americans, if they explained them to ordinary people and if citizens learned them, it could lead to progress in democratic development.” (Baku, men)

“American imperialism and Zionism place dictators in all small countries and plunder the wealth of these countries. The U.S. claims that it is a democracy and defends human rights, but in fact it is not true. The U.S. is only protecting its own democracy, its own citizens’ rights. America devastates the wealth of other countries. America’s policy is to diminish and devastate all small nations of the world so the American people and Zionists live well.” (Baku, men)

After praising American technology and high wages, panelists cautioned that U.S. foreign policy “interferes in the internal affairs of many countries,” as one focus group participant in Sabirabad put it. In contrast, they described Russia in more glowing terms:

“The great Russian people ensure the future of the whole world. They also have a president who is like the Great Alexander of Macedonia. He will restore justice and democracy in the whole world. Russians will also ensure a bright future of the Caucasus, Europe, Latin America, and maybe even U.S.A.” (Baku, men)

“Among [Turkey, Russia, and the EU], I prefer Russia. I see democracy and economic development in Russia. Russia is the superpower among the world's countries; presently they have democracy, economy, and advancement. People are still humanist, laws work, this is a strong state.” (Baku men)

One Baku male respondent, after spontaneously blaming the Ukraine conflict on “U.S. and British imperialist forces,” said he had read in the newspaper that the United States is “preparing a revolution in Azerbaijan,” “wants to create disorder” to obtain oil, and tries to “undermine our relations with Russia” — all elements of the Russian government’s critique.

ASKED WHICH COUNTRIES Kyrgyzstan should cooperate with, all six of the Kyrgyz groups strongly endorsed Russia, China, or one of the country’s Central Asian neighbors; none mentioned the United States. When specifically pressed about the possibility of cooperating with America, Kyrgyz participants were overwhelmingly skeptical:

“We do not need [the American] political system here.” (Bishkek, highly educated)

“What the American system comes to is evident in Syria, Ukraine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon.” (Bishkek, highly educated)

Participant 1: “America has contributed to the depletion of the world’s resources, and eventually there will only be enough for a billion or half-billion of population. So America has a plan to gradually capture everything; they keep everything in their country, crude oil and everything, and use up other people’s, because when everything else is exhausted, they will then still have their own resources.”

Participant 2: “That’s why they are conquering the Middle East.” (Bishkek, highly educated)

“They very much want to seize Siberia.” (Bishkek, highly educated)

Kyrgyz participants decried American permissiveness toward children, and lack of respect for elders (Bishkek, less educated). They discussed America’s remoteness compared to Russia, wasteful and pro-Uzbek American humanitarian spending (Osh, ethnic Kyrgyz), and America’s use of aid to interfere in Kyrgyzstan’s internal affairs (village near Osh, women).

Yet these criticisms were tempered with occasional praise for aspects of the American way of life. One respondent said Kyrgyzstan could follow the American example to “learn and protect our rights” (Osh, Uzbeks). Another reported the positive experiences of acquaintances living in the United States:

“A friend of mine has been living in America for 10 years. He says that in five more years, he will own his house. He took a 20-year mortgage loan to buy a house, and lives quietly. Both he and his wife are working and they are not hard up. They have a low interest rate. So he can sometimes travel, he transfers money to his parents, and he says that at this rate, he can pay off the loan in six-to-seven years. … We do not have such possibilities here.” (Bishkek, less educated)

Such sentiments were drowned out by concerns about American foreign policies, as well as overt support for Russia:

“I think they have a very strong economy with greatly developed technologies. We can benefit from cooperation with them in terms of economy and technology. But America does not respect Muslim people. From this perspective, I am against [America]. Because look at what has happened in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq — they came there and started internal conflicts, then left. And I think that what is happening now in Ukraine, as well, is their fault. Because they are really jealous of Russia, and we support Russia. Russia is taking care of us.” (Village near Osh, women)

Skepticism about protests and NGOs

RESPONDENTS IN Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia discussed protests and political NGOs in negative terms straight out of the Russian talking points. With near unanimity (excepting some dissent in Kyrgyzstan), they said protesters against the government are paid troublemakers rather than true devotees of their stated causes (a standard Kremlin claim since the Orange Revolution), and they condemned protests as potential sources of instability:

“To hold meetings and demonstrations means to act against the interests of our state and society. All citizens should protect and support our political stability and order. Only then will all urgent challenges facing our country be successfully solved. Destabilization works in favor of our enemies and detractors. We all need to fully support the policy of the leadership of the country.” (Sabirabad, men)

“I am against [protests]. Note that wherever they have had protests has turned out to be a sad state: take a look at Egypt, Ukraine. I think that meetings and demonstrations are very harmful.” (Sabirabad, men)

Kyrgyz and Azerbaijani participants expressed modest, if ambivalent, approval of NGOs that perform charitable tasks, but little familiarity and even less support for NGOs that pursue political causes. One Bishkek respondent quipped that there will be a lot fewer of them after the closure of the U.S. air base in Manas.

In stark contrast, the Ukrainian groups were much more divided regarding the merits of protests, with some strong supporters:

“[Protests] can affect things, can help them change. … They express to the authorities that people are dissatisfied with something.” (Lviv, under 30)

“[Protests] show the authorities that they are not invulnerable and all-powerful. They are only in power so long as we support them; if they lose our support our support, we have the ability to take them down.” (Lviv, under 30)

The Ukrainians’ support for social service-oriented NGOs was stronger than we observed elsewhere, and they even expressed mixed views about political NGOs. While these positive views of standard civil society institutions were contested in the Ukrainian groups, they nonetheless stood out in their reluctance to embrace the Russian critique of protests and NGOs.

Conclusion

FOCUS GROUPS MAY NOT be representative of the populations from which participants are drawn, and the generalizability of these results remains to be confirmed with survey data. However, the recurrence of the main themes across groups within and between countries implies that these views are not idiosyncratic. The core arguments made by Russian officials regarding America’s ambition, arrogance, self-interestedness, and penchant for using democracy promotion to meddle in the affairs of others, resonate with publics across Eurasia — even in countries like Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, which have received significant amounts of American aid, and Azerbaijan, which has sought to maintain some diplomatic distance from Russia. The appeal of the Russian critique poses a formidable challenge to American soft power.

To restore a positive image of America, U.S. officials should scale back the type of democracy promotion that looks like meddling in favor of strategies that leverage America’s advantages — namely, positive perceptions of American institutions, economic, and technological achievements, and high living standards. The American way of life could be made a positive institutional model that ultimately encourages organic movements for change untarnished by the stain of foreign interference. Ways to do so include bolstering student, scientific, and other exchanges, encouraging more frequent travel, immigration, and trade between the United States and former Soviet countries, and quietly but assiduously promoting programs that expose citizens in Eurasia to concrete examples of American institutions. It is telling that many of positive views of America expressed in the focus groups originated from acquaintances of participants who have spent time in the United States.

While no strategy is guaranteed to work, this approach has a better chance than continuing efforts to promote democratization by directly supporting local political NGOs and oppositional movements.

* * *

Theodore P. Gerber is a professor of sociology and director of the Center for Russia, East Europe, and Central Asia at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Jane Zavisca is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Arizona.

This material is based upon work supported in part by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Research Office via the Minerva Research Initiative program under grant number W911NF1310303.

Cover image courtesy of Shutterstock/Genova