Winter 2016

In the age of Trump, what does it mean to be “classy”?

The long, hot, summer of Trump prompts a question about one of the billionaire’s favorite words: what does it mean to be classy?

Donald Trump is back, and so is his mouth.

Since he announced his presidential candidacy in mid-June, the fast-talking billionaire’s unique way with words has drawn as much attention as his policy proposals. Dissections of his speaking style have varied. Some commentators have taken a scientific approach. The popular linguistics website Language Log, for example, is probably the only place to grade the former Apprentice host by the likes of “weighted log-odds-ratio, informative Dirichlet prior,” which they did in September. In October, the Boston Globe published an analysis that concluded that Trump spoke at a fourth-grade level, the lowest of all major candidates for president. (The jury, however, is still out on the Globe’s methodology.)

Most outlets and blogs, though, haven't bothered with the fancy science, opting instead to poke fun at Trump’s speech on simpler grounds. In particular, these critics seem to take special glee in mocking Trump’s use of the term classy. For evidence, think about all the headlines that scrolled past your Twitter feed this summer, like this one from Mother Jones: “If You Don’t Click on This Classy Post, You Are a Loser and a Moron.” Other participants in the surprisingly bipartisan cackling squad include the Washington Post (“Waiting for a ‘Classy’ Trump Presidency”); The Week (“The 8 Funniest Lines from Donald Trump’s Classy, Major, Quality Presidential Campaign Launch”); The Daily Beast (“Meet Donald Trump’s Super Classy Cabinet”); Reason (“Trump Tops His Ultra-Classy Debate Performance by Suggesting Megyn Kelly’s on the Rag”); Slate (“Donald Trump Steals Jeb Bush’s Tax Plan, Makes It Classier, More Luxurious”); The Daily Caller (“Is Donald Trump a Classy Conservative — or the Classiest?”); Salon (“Not Classy: Donald Trump Calls Fox News Critic in Wheelchair a ‘Loser’ Who ‘Just Sits There’), and so on. The list is longer than a stretch limousine from the ’80s.

This isn’t the first time that Trump has been dinged for his overuse of the c-word. In 2011, in a more measured diss befitting the Times’s editorial page, Timothy Egan scolded would-be candidate Trump for his boorishness and birtherism. In the process, Egan made a long and remarkably astute comparison to another turgid billionaire-turned-politician, Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. “Trump and Berlusconi revel in all those things your mother said not to do,” wrote Egan. “They’re crude, obnoxious, boastful and bullying.” Refusing to pull his punches, Egan came to a devastating conclusion: “They are the opposite of classy.”

You get the idea. While pundits of all persuasions are having a laugh at Trump’s expense, for liberal critics of Trump, classy has evolved into a perfectly ironic mock, nestled somewhere in the drawer between “bringing democracy” and “religious freedom bill.” The long, hot summer of Trump had me thinking: what does it mean to be classy?

What does it mean to be classy?

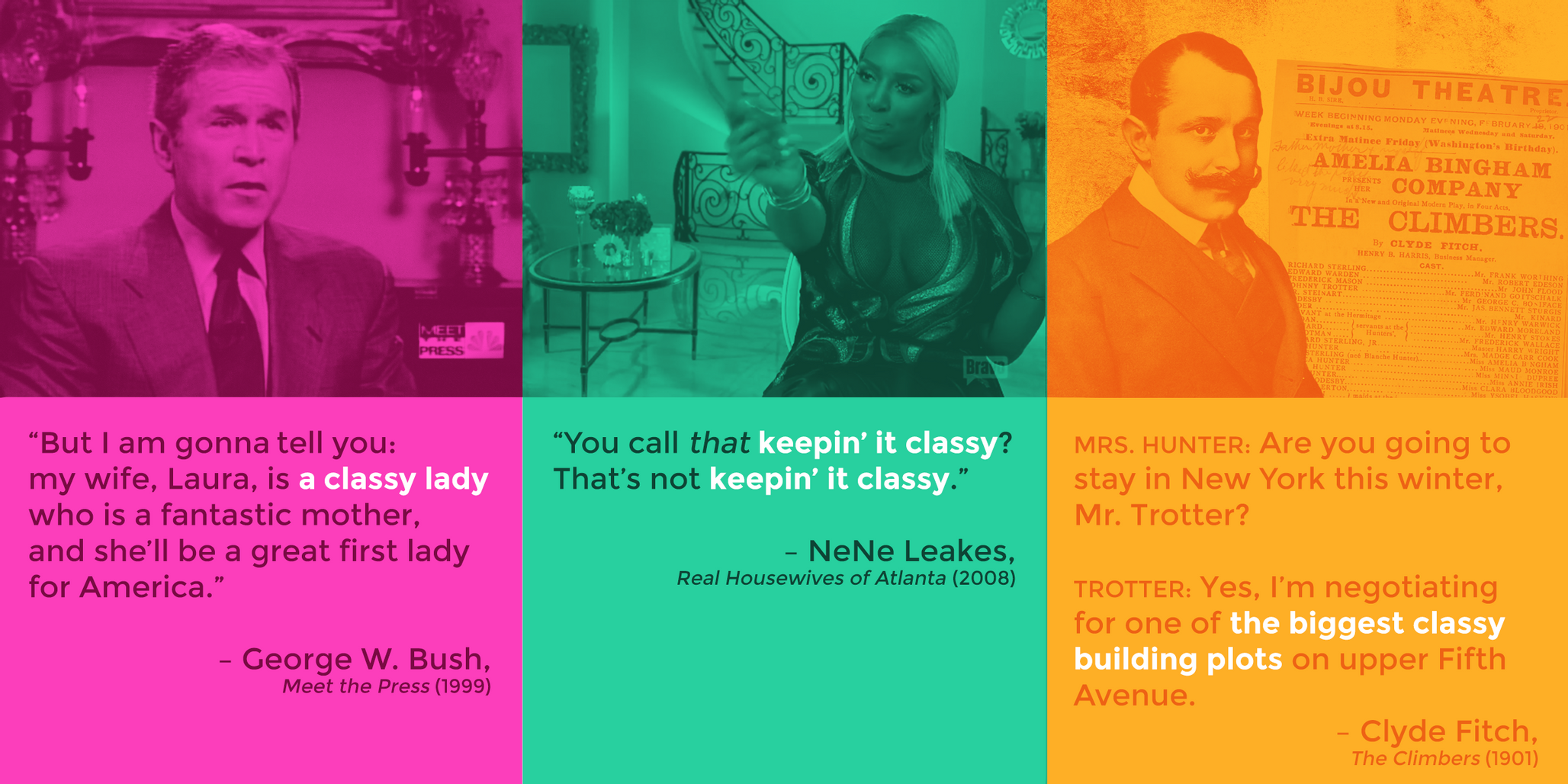

Probably unsurprisingly, classy modifies the word “class.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “class” comes from Middle French, but classy is a relatively new term. The OED’s first record of it comes from the dedication to the 1868 British comedy Cyril’s Success. In his note, the play’s author, Henry James Byron, attempts to defend his fans from snobby judgment. “Although [Cyril’s Success] is to a certain extent ‘classy,’ I can assure those critics who think London and provincial audiences care only for sensation and extravagance … that it ‘went’ (to use an actor’s phrase) with remarkable effect.”

For the time being, classy seemed to have been confined to Victorian England, possibly just London. The next work to include it was a novel, An American Girl in London, a cheeky report about life as a young single woman abroad. The book’s author, Sara Jeannette Duncan, was actually Canadian, but she had been living in the city. In the story, one of the narrator’s hosts invokes classy to question why the narrator doesn't join up with a group of people (“not classy enough, eh?”). Next up was an 1892 volume of the status-centric London literary magazine Temple Bar, a sort of New York magazine of its day. Among its offerings is an essay titled “Creatures of Transition,” which takes on the task of dissecting the latest generation. Among the exotic creatures of fin de siècle England, the author finds, is the “‘smart’ young married woman.” She is “married to a man much older than herself,” or is at least independently wealthy. She “makes no puddings, mends no stockings, and visits not the sick,” but is “chic and ‘classy.’”

In the United States, the word’s debut in print appears to be in an 1890 issue of the Harvard Lampoon. It’s limited to a groan-inducing zinger that involves a character named “Classy Cuss,” but that seems to be it. According to Brigham Young University’s Google Books corpus, there weren’t any other mentions of the term in an American publication in the 1890s.

Though there seem to have been only a handful of mentions of classy in the first decade of the century, the turn of the twentieth century was looking up for the scrappy new modifier. In 1901, classy was given its first big audience on Broadway in W. Clyde Fitch’s play The Climbers. It seems like just the adjective Fitch was waiting for, which may explain why it was uttered no less than nine times in the “satirical portrait of manners,” as a Times review described the production. The next sighting may have been in The Metropolis, Upton Sinclair’s damning 1908 novel about the lifestyles of New York’s rich and obnoxious. A group of aristocrats are described as “exceedingly ‘classy’; they affected to regard all the Society of the city with scorn, and had their own all-the-year-round diversions — an open-air horse show in summer, and in the fall fox-hunting in fancy uniforms.”

It was only a short time later that classy began to appear in advertisements, suggesting that the word had oozed into the mainstream and middle class, at least in certain areas. The Alan-Higgins Wall Paper Company of Worcester, Massachusetts, advertised its “Classy Wall Papers” in a 1908 issue of the quirky, Aurora, New York-based literary magazine The Philistine. Between its reporting and advertisements, a 1909 issue of the Boston-published Shoe Retailer and Boots and Shoes Weekly notched more than a dozen classys. The same year, in a different Boston-based footwear trade journal, Boot and Shoe Recorder, companies that advertised the classiness of their goods included manufacturers from Webster, Lynn, Campello, North Adams, and other towns throughout the Bay State.

A Massachusetts connection seems to loom large here. Playwright Fitch — who was a reputed paramour (and confirmed friend) of London resident Oscar Wilde — had graduated from Williams College in Williamstown. Between these multiple connections, the early Harvard Lampoon reference, and the close cultural and transport links between Boston and London, it seems like a decent possibility that the long and winding road to classy leads back to Massachusetts.

However it made its way to the new world, classy was definitely sticking around. Between the first decade of the century and the period between 1910 and 1920, the Google Books corpus records an increase in mentions of the term from 192 to 1,045. In a 1914 article in the U.S. Navy’s official magazine, Our Navy, the budding national craze for classy is on clear display. In a recap of a sailor’s ball held in Vallejo, California, the author marveled at the “classy music, classy flowers, classy programs, classy punch, classy eats and last, but not least, a real CLASSY crowd.” Classy, Mr. Trump might say, was huge.

For the next 80 to 90 years, classy was used in its original form. If you doubt this, allow me to counter with an excerpt from a Hall and Oates concert review published in the New York Times in 1976. In the review, John Rockwell concluded that the band’s sound “may not often rise to the heights of celebratory release, but it is genuinely classy pop music.” If a rock critic — the most jaded, sarcastic creature working in letters — could bestow the term on notorious smooth rockers Hall and Oates, I think we can agree that classy hadn’t yet entered its ironic stage.

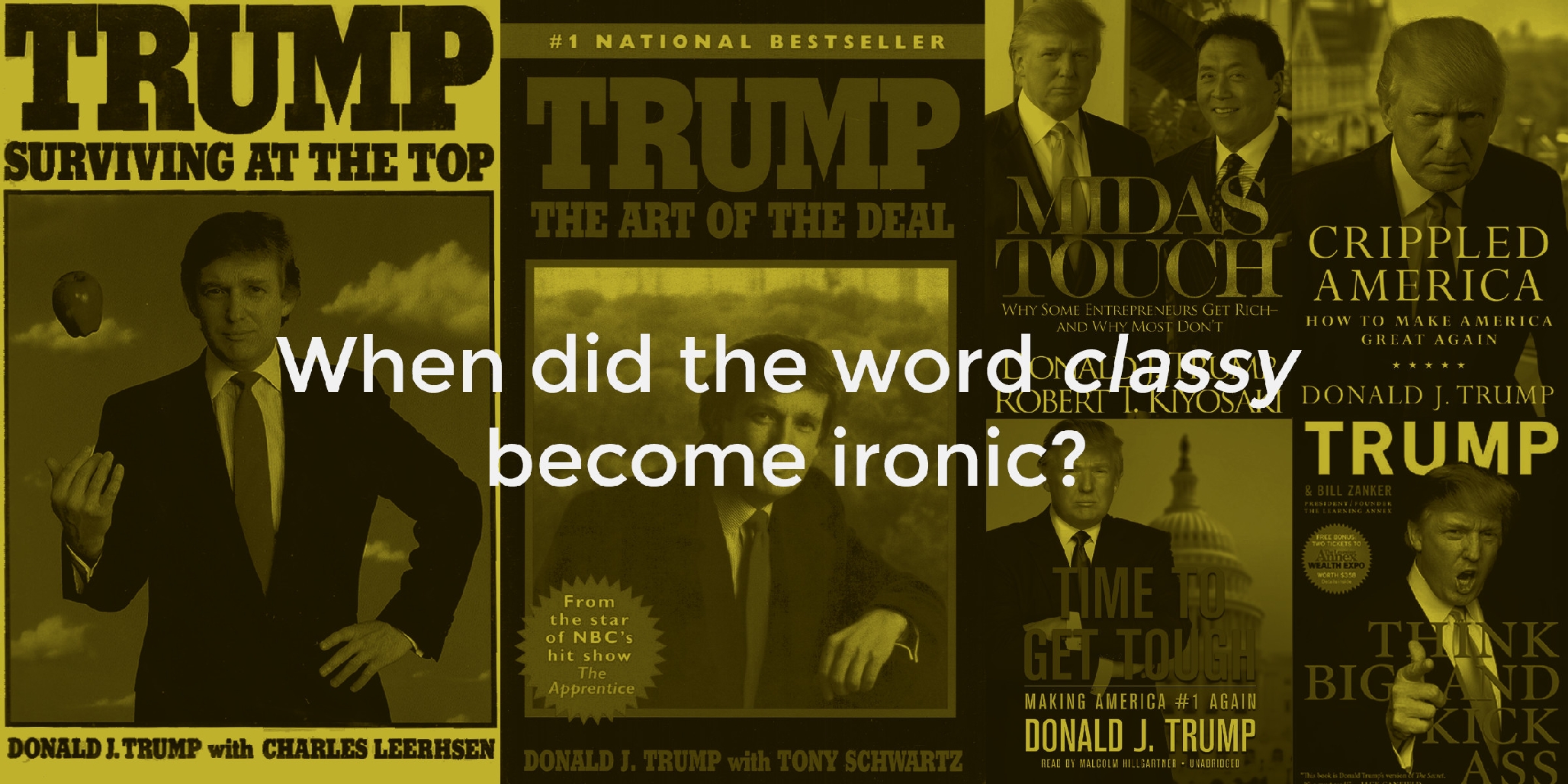

The late ’80s was a very classy time in America. A younger, less-scowlier Trump published not one, but two bestsellers within just a few years, The Art of the Deal (1987) and Trump: Surviving at the Top (1990). The culinary tastes of President George H. W. Bush earned pork rinds that most improbable of adjectives in a 1989 New York Times headline: “Suddenly, Pork Rinds Are Classy Crunch.” Classy was as popular as ever.

To take one random but representative example, the personals section in the May 1990 issue of Orange Coast, a southern California lifestyle magazine, featured multiple ads that were either seeking a classy woman or were posted from self-described classy women. Two typical posts:

Introvert, feminine, redhead, 43, 5’2”, intelligent, classy, sexy, sense of humor, sometimes shy Ph.D. A brain for business and a bod for sin. Seeks to share romance and friendship. Photo/note.

Dynamic, successful, adventurer, business professional, 40s, 5’11”, with varied interests and a broad comfort zone (black tie or jeans), seeks intelligent, classy, humorous, special lady, 30–40, to share soft heart, tenderness, and travel. Warm, honest relationship with possible commitment. A note/photo/phone could open new horizons for us both.

Judging from the magazine’s distribution area and advertisers, which included luxury car dealers, plastic surgeons, home-remodeling companies, and other predators on the insecurities of the status-minded, we can infer that its target audience was affluent strivers. The term shows up as well in personals in similar lifestyle publications across the country, including Cincinnati Magazine, Indianapolis Monthly, Los Angeles magazine, and New York magazine. All of this suggests that classy was still a straightforward, positive word among the country’s middle or upper-middle class. And yet.

Classy has become the yacht of adjectives.

Today, classy “is kind of a weird word,” Betsy Rymes, a linguistic anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told me during a phone interview. “People have two ideas about the word ‘classy.’ The first is that it’s sort of somebody who has class or seems high-class. The other, which seems like it’s gotten so saturated with sarcasm and irony, is used just as often to mean the opposite, like super-slutty or tasteless.”

How did it come to this? I pestered a number of linguists and discourse-watchers to help me sort it out. None could point me to the exact moment when classy split off to Ironyville, but they had some good theories as to how it might have happened.

The process is pretty uncomplicated. “When something like ‘classy’ gets associated with a divisive figure like Trump, it tends to take on meanings associated with Trump as well,” says Nic Subtirelu, a Ph.D. candidate in applied linguistics at Georgia State. “Words are not simply namers of things; they also end up taking on the property of those things as well.”

“Words are not simply namers of things; they also end up taking on the property of those things as well.”

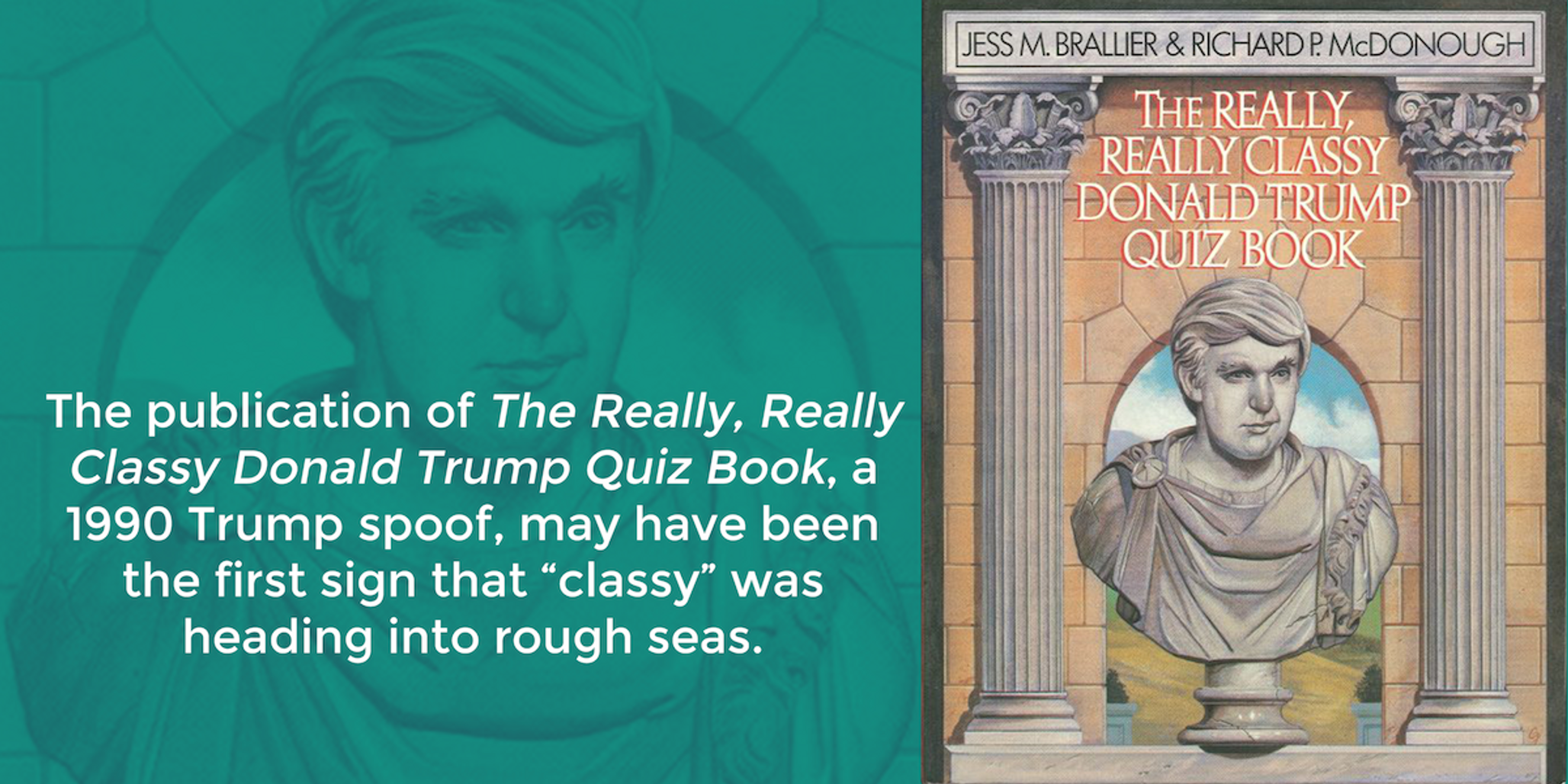

As the public, conspicuously tanned face of classy, Trump brought new attention to an unremarkable old term. Consequently, even by the ’90s there were stirrings that all was not sunshine and monogrammed cufflinks for the word. The publication of a Trump spoof called The Really, Really Classy Donald Trump Quiz Book (1990) may have been the first sign that the yacht of all adjectives was heading into rough seas. Six years later, an issue of SPY magazine lamented a certain Manhattan real estate developer’s “classy decision to pollute our local ecosystem with a renovated Gulf and Western Building.”

For the most part, the ironic use of classy seems to have been limited to a select band of scolds. In 2004, however, classy had its mainstream moment. That summer, the comedic film Anchorman was released, introducing American moviegoers to Ron Burgundy, the dapper, dense 1970s newsman played by Will Ferrell. Every evening, while his favorite bottle of Scotch sat nearby, the mustachioed TV anchor signed off his evening newscast by commanding his audience to “stay classy.” The success of the movie, which came out near the peak of Ferrell’s popularity, may be a big reason why classy became the lazy putdown we know today. One strong proponent of this theory is Deadspin writer Samer Kalaf, who charted the signature phrase’s rise in a 2013 article, “Fuck You, ‘Stay Classy.’” In the post, Kalaf complains that “‘Stay classy’ is a tool of smarm for dumb people. Well, dumber people. It says, ‘I, a person with class, think your action does not have class, though I will not deign to explain why not. Also, I saw that movie everyone else saw.’”

Still, despite its evolution into sarcasm, many people still use classy with sincerity. Another pop culture example is informative: on the Real Housewives reality TV show franchise, there’s no higher calling than being considered classy. It may seem counterintuitive, but the fact that classy is being aspired to actually means that, at least for some people, the word has retained its power, says Lauren Squires, an Ohio State University linguist and author of the 2014 journal article “Class and Productive Avoidance in The Real Housewives Reunions.” “The way in which these women — mostly American women — use this word has to come from their sense of its normative use,” says Squires.

For the Housewives, classy “means something about behavior: behavior that accords with a person’s station in life, which is one of privilege and politeness,” Squires told me in an interview. However, what constitutes acting classy is “always being negotiated,” she says. “It’s a term that’s being fought for in the face of transgressions against it. I think to be ‘classy’ for a woman who lives in the Upper East Side is probably different for what it means for a woman in Beverly Hills with money or for a woman in Atlanta with money. It probably means something different to men than for women,” as well.

A quick survey of pop culture confirms that classy-classy is far from dead. On August 31, 2015, the day after this year’s MTV Video Music Awards, the popular New York hip-hop radio station HOT97 tweeted this question to its listeners:

Was #NickiMinaj being classy or trashy for calling out #MileyCyrus at the #MTV #VMAs?

There’s no irony here. For HOT97 (and likely for much of their Twitter audience, which numbers over 650,000), classy has much the same meaning as it did for nineteenth-century British playwrights. Like the Housewives, the author of this tweet reveals that their perception of classy is still positive, almost affirmational.

If Trump stays in the limelight long enough — four more years, perhaps? — he just might ruin classy for good.

That said, classy shouldn't rest on its (surely gold-encrusted) laurels. If enough negative associations accrue, a word may undergo “pejoration,” says UNC sociolinguist Connie Eble, using the term for what happens when a word evolves into something with bad connotations. As an example, she cites the Southernism “bless your heart,” which has evolved from an earnest expression of gratitude into a sharp-elbowed passive-aggressive insult. “I'm still utilizing it the old way,” she says, but her students definitely aren't. “I said to my class, ‘bless your heart,’ and they started laughing.”

If Trump stays in the limelight long enough — four more years, perhaps? — he just might ruin classy for good. “People may not want to be referred to as ‘classy’ if it means they show characteristics of Trump,” says Eble.

In Rymes’s view, classy’s breakaway into sarcasm has less to do with word dilution than it does with changing attitudes. “I don’t really think it’s a matter of when the word ‘classy’ changed,” she says. “People just use language in a more ironic sense.”

At least, they have been. She does add that some of her younger students seem to be way more earnest than their predecessors. “They’re more into starting nonprofits, things that people in their 30s are more cynical about.” In the view of this thirtysomething, that’s totally classy.

* * *

Adam Rosen works in academic publishing in Asheville, North Carolina, and is a past contributor to the Wilson Quarterly. Find him online at adammrosen.com or on Twitter at @adammmmmrosen.

Cover photo courtesy of Flickr/Elliott Blackburn

.jpg)