Winter 2012

Why did the American Revolution happen? The economy, stupid.

American patriots were often forced to subsume their economic frustrations within a broader argument for sovereignty.

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal," may be among the most famous phrases in the English language. Similarly inscribed on the hearts of Americans are the personal liberties the Declaration of Independence enshrines. But “the final text of the Declaration was anything but a transparent ranking of all the real reasons for independence,” argue Staughton Lynd, an independent scholar, and David Waldstreicher, a historian at Temple University. Economic frustrations, not a desire for “certain unalienable rights,” planted the seeds that grew into the American Revolution.

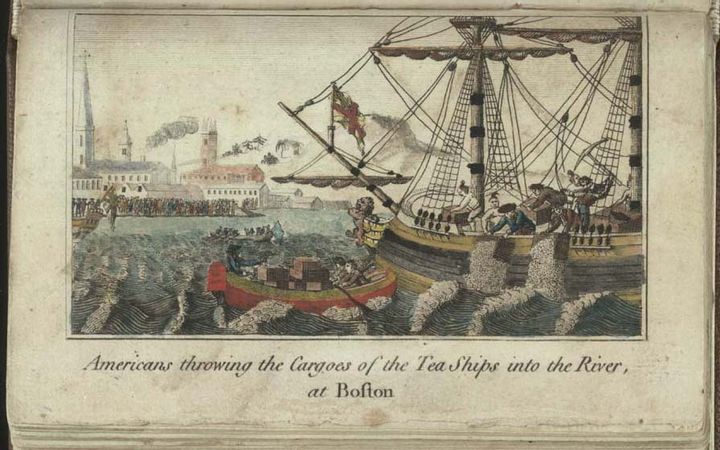

Scholars tend to view the ideological arguments for independence as building to a critical point and preoccupying the colonists thereafter. That’s inaccurate, Lynd and Waldstreicher write: From the mid-18th century right up to the signing of the Declaration, Americans objected to a myriad of British imperial policies principally on economic grounds. The anti-tax sentiment of the Boston Tea Party in 1773 is well known, but Americans also protested British attempts to requisition resources during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), imperial currency manipulation that left the colonies strapped, and prohibitions on trade with the French West Indies, along with many other policies.

To make the strongest case possible, American patriots were often forced to subsume their economic frustrations within a broader argument for sovereignty, setting up the natural rights arguments associated with the Declaration. The debate over the Navigation Acts during the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774 was one such moment. These laws required that American rice and tobacco be shipped to England so that British merchants could resell the commodities for marked-up prices and reap the rewards. “In arguing for the conclusive right of the colonists to govern the relationships among the colonies and between them and other countries, airtight precedents were lacking,” the authors note. There were no common-law traditions or charters to back up their arguments. The “principles of justice,” however, could do the trick.

There’s nothing wrong with the fact that colonists were initially motivated by economic concerns, Lynd and Waldstreicher say. What’s dismaying is that principles such as the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” seeped into the mythology of the American character at the expense of everything else and fed the belief that America is an exceptional nation. In reality, the authors assert, “the American Revolution was basically a colonial independence movement and the reasons for it were fundamentally economic.”

* * *

The Source: "Free Trade, Sovereignty, and Slavery: Toward an Economic Interpretation of American Independence" by Stuaghton Lynd and David Waldstreicher, in William and Mary Quarterly, October 2011.

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress